Aaron Sanchez is getting his shot at the rotation the last way he’d ever want it, but the Jays’ newest ace-in-waiting knows his injured buddy always has his back

By Arden Zwelling in Palm Harbor, Fla.

On a brisk Monday afternoon in mid-February, Aaron Sanchez and Marcus Stroman bounced out of the semi-detached condo they share in Palm Harbor, Fla., and loaded into Stroman’s pimped-out, matte charcoal Audi S6, along with three of Stroman’s friends from back home—Chris, Ryan and Joe—to make the two-hour drive to Orlando for WWE Raw.

They were buzzing. They knew they had good seats, kindly provided by Stroman and Sanchez’s agency. But they didn’t know how good they were until they got to the arena and walked down the aisle—all the way to the first row, behind the commentators, close enough to reach out and tap Booker T on the shoulder. They had so much fun. They wore Wyatt Family sheep masks; Dolph Ziggler pointed them out; they took selfies with wrestlers while the matches were in progress. Nobody gets to do that.

At one point, as the broadcast went to commercial, you could see Stroman, on-brand in a black HDMH (Height Doesn’t Measure Heart, Stroman’s clothing start-up) shirt and black Toronto Raptors hat, standing in the front row, raising and lowering his arms in unison with wrestler Daniel Bryan right in front of him—“YES! YES! YES!”—mugging for the cameras with his boys like a scene out of Entourage. It’s true, sometimes their lives can seem like a TV show. Getting recognized at the Eaton Centre; playing in charity golf tournaments with celebrities; hopping on chartered flights across the continent; having cameras and microphones in their faces as soon as they finish their day jobs; having tens of thousands of fans following their lives on social media. As Stroman and Sanchez lost their minds in the front row, their photos blew up Twitter and Instagram feeds of Jays fans up north who were catching wind of the two young pitchers having the time of their lives.

Something about these two appeals perfectly to Toronto’s long-suffering, meme-loving, desperate-for-any-smidgen-of-hope-please-just-let-us-have-nice-things fan base. When Stroman blew out his knee less than a month before opening day, you could feel the thud of hearts hitting floors across the city. It really hurt. It hurt not only because Stroman has that a mix of exceptional talent and universal likability that’s rare in professional sports. It hurt because for half a decade, since Alex Anthopoulos took over the club, fans have been promised this team will be built the right way, through youth and development, and that one day, all the draft picks the club has hoarded and all the scouts they’ve hired will pay off. And it looked like it was, with Stroman and Sanchez here, the first of Toronto’s young crop of home-cooked pitching talent that also includes Daniel Norris, Roberto Osuna and Jeff Hoffman. They’re both eager, savvy and bright—Sanchez scored an 1820 on his SATs, Stroman 1810, good enough to have their pick of colleges—with a keen nose for fan interaction and a feeling of owing something not only to the club, but to the viewing public. There was an awful lot expected of these two; this was going to be the year.

But Stroman’s going to miss that year, and Sanchez will have to soldier on without his closest comrade. The expectations, however, haven’t changed. For the Blue Jays to capitalize on their window for contention, which has been open for two years now with disappointing returns, Sanchez will need to deliver, whether it’s at the back of the bullpen or in the starting rotation spot vacated by Stroman.

That pressure can be hard to escape. Perpetually connected to everything and everyone they know, as all 20-something kids are, Sanchez and Stroman don’t get much time away from the stress of their professional lives. Being a ballplayer in this era isn’t a strictly at-the-ballpark thing—it’s an all-the-time thing. Even when they go home after a 10-hour day, the first thing the boys do is scroll through texts, open Twitter, pull up Instagram and consume themselves with what everyone’s saying about them. Stroman’s first public comments after his injury came via Twitter, where he told the world he was “beyond devastated.” He said he “still can’t believe it” and retweeted and favourited the messages of support that were flooding in. Stroman’s more active than Sanchez in terms of posting his thoughts, but they’ve both been warned by friends, teammates and management about spending too much time in that world. Neither of them are listening. Not out of hubris or rebellion, but because they don’t think their lives are all that exceptional. “Honestly, the reason I do it is because when I was younger I always thought, like, how cool would it be to see what Michael Jordan’s doing right now? You just see these superhuman athletes on TV and don’t realize they’re normal people,” Stroman says. “It was as if they had their own world. Like they don’t go to the supermarket, they don’t eat at normal restaurants. But we’re just normal kids doing normal things. We’re just trying to live out a dream like everyone else. It’s not like we’re anything special. We just play baseball for a living.”

Stroman’s upbringing is fairly well-known. His parents separated when he was young, and he spent his childhood splitting time between living with his mother, Adlin, a loving, nurturing influence, and his father, Earl, a detective in Suffolk County, N.Y. Earl made it his mission to instill work ethic and discipline in his son, forcing him to run sprints, work out and do extra homework while other kids were at the mall, wasting time. It was tough for Stroman, and there were times he hated it. But talk to him today and he’s overwhelmingly appreciative of each parent’s influences. He believes he never would have made it to the majors without them pushing him as hard as they did.

Sanchez’s youth, however, has seldom been talked about, perhaps because it’s not the average American upbringing. When his mother, Lynn Gesky, was pregnant with Aaron, she decided to pack up and leave his father, Frank Sanchez, taking her first son, Andrew, with her. They moved in with her family and shortly thereafter she met a building inspector and former baseball player named Mike Shipley.

Shipley, a tall, left-handed pitcher, played a couple of seasons at Barstow Community College before moving to the University of Tulsa for his junior season, finishing fifth in the NCAA in strikeouts. The California Angels drafted him in the 10th round of the 1976 draft and let him go back to Tulsa for his senior year, where a rotator cuff injury ended his baseball career.

With six-month-old Sanchez’s biological father out of the picture, Shipley took over, providing bottle feedings and diaper changes. Sanchez would sometimes see his father on weekends, but he can’t remember anything about their relationship. What he does remember is being in Grade 5 and finding out there would be no more weekends away from his mom’s place because his father had died. Sanchez says he doesn’t know how Frank died—he’s never asked and never will. He just knows he made a decision when he was young to carry on the Sanchez name, primarily for his grandparents’ sake. For a time he thought about being Aaron Shipley; it’s how he identifies. But he couldn’t bring himself to do it. “I don’t know the whole story, and honestly, I don’t care. I know who my dad is. My real dad made me. But [Shipley] is my dad. He raised me. When I was a kid, I wanted to be on a playground with him, not with my real dad,” Sanchez says. “It’s not like I felt negatively towards him. He just wasn’t around.”

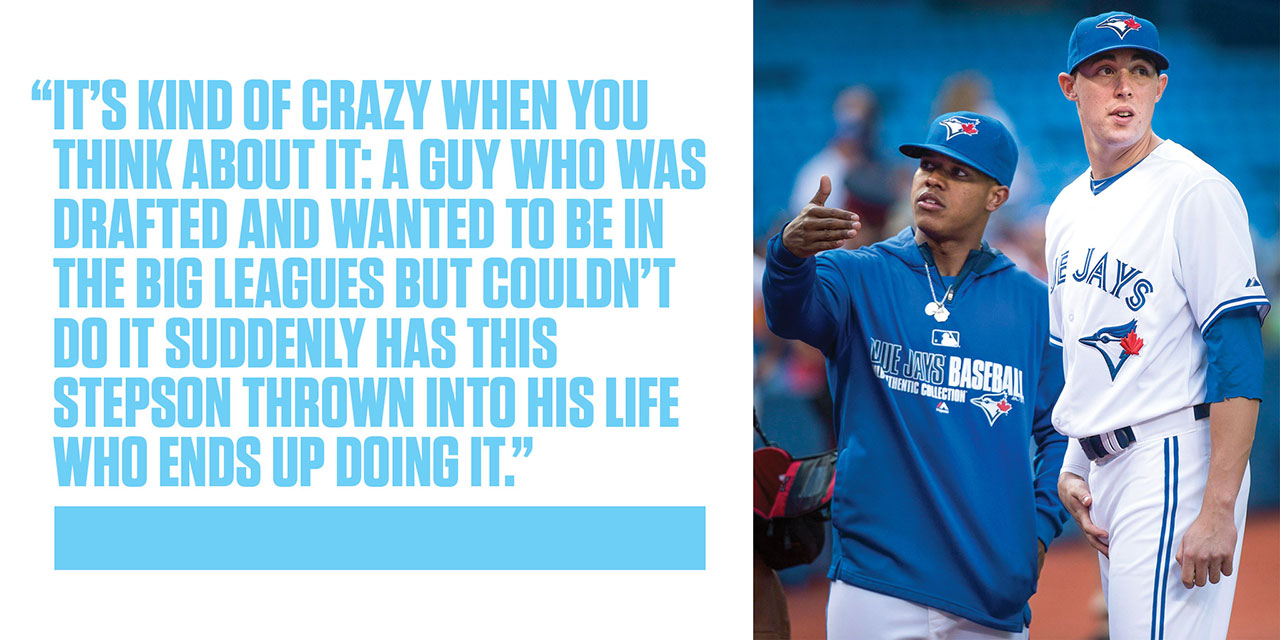

Sanchez’s biological father never played sports; neither did his uncles. His mother had zero interest in them, preferring to keep Sanchez focused on school. Shipley got Sanchez into the game, driving him to travel ball games starting in Grade 8, which were always a minimum of an hour and a half away from secluded Barstow, Calif. He was there with Sanchez for his starts in high school when nearly 100 scouts would come out to see him pitch. Shipley guided Sanchez through the draft process, meeting with agents and scouts. “He’s been my mentor throughout this entire thing. I can honestly say that without him, I wouldn’t be here,” Sanchez says. “It’s kind of crazy when you think about it. A guy who was drafted and wanted to be in the big leagues but couldn’t do it suddenly has this stepson thrown into his life who ends up doing it.”

Really, growing up, Stroman and Sanchez couldn’t have been less alike. Stroman is a cocky kid from Long Island, who liked shopping in the big city and talking smack after punching batters out. Sanchez is a quiet kid from a tiny town on the desert highway between L.A. and Vegas—Oct. 20 is Aaron Sanchez Day in Barstow, in recognition of the town’s first major-leaguer. Stroman was always undersized and battled doubters throughout high school; Sanchez was tall and lean, a can’t-miss prospect by his mid-teens. Stroman reached pro ball at 21, after college; Sanchez at 17, straight out of high school.

But when their mutual agent, took them both out for dinner at a Tampa steakhouse during the Florida instructional league in the fall of 2012, something clicked. Stroman was new to the franchise, having only been drafted three months earlier. Sanchez had been around, but had recently seen many of his best friends traded away as the Blue Jays shifted into win-now mode and started dealing prospects. “The guys I hung out with weren’t around anymore; Marcus just showed up and it was automatic,” Sanchez says. “We started hanging out all the time.”

They decided to live together the following spring, in the second-floor apartment Sanchez rented in Palm Harbor. When the season started, Sanchez was assigned to high-A Dunedin. Stroman remained in Dunedin because he was suspended at the time—thanks to a positive test for a banned stimulant he says he unknowingly ingesting through a pre-workout supplement—so he had plenty of time on his hands. He’d watch Sanchez’s starts, and the pair would deconstruct them back at the apartment. By May, Stroman had served his suspension and headed off to New Hampshire to pitch in double-A. They talked constantly and counted down the days until they were reunited that October in the Arizona Fall League, where they lived together once again.

In 2014, their first year at big-league camp, they moved into the condo beneath Sanchez’s old place—Stroman bought it two days after he found out it was on the market—for spring training, until Stroman went to triple-A Buffalo to start his season and Sanchez went to New Hampshire. By May, Stroman was in the majors, texting Sanchez daily about how awesome everything up there was. It was like going from coach to first class. He rented an apartment near the Rogers Centre with an extra room he left completely empty. Stroman took a picture of the room and sent it to Sanchez, saying, “It’s waiting for you, man. When you get called up, it’s here for you.” That day came in July. After pitching an inning of scoreless relief for the Buffalo Bisons in Pawtucket, R.I., Sanchez was summoned from the showers and, still wearing his towel, was told to pack his stuff and head to the airport the next day. He immediately called his parents, but neither of them picked up. Then he called Schofield, who wasn’t answering either. Then he called Stroman. “I was so hyped. I was ecstatic. I was jumping all over the apartment,” Stroman says. “The entire next day I was just like, ‘When is he going to get here? When is he going to get here? When is he going to get here?’ He moved right in.’”

That was the last extended period Stroman and Sanchez have been apart. Other than trips home for the holidays, the pair have been at each other’s sides for practically every moment since. They hung out together in the off-season, worked out with Jose Bautista in Tampa in early January and were in Dunedin before spring training opened. This year they were planning on renting an even larger apartment in Toronto, with a third room for visiting family. “The experience of being in the big leagues is crazy on its own,” Stroman says. “Getting to do it with one of your best friends is phenomenal.”

Even if he’s not pitching beside him this season, simply having someone like Stroman to go to for advice on the daily life of a big-leaguer is great for Sanchez, who figures he said about 10 words total to the rest of the team in his first week with the Blue Jays. “It’s like being a freshman on varsity again. You don’t really know how to act,” Sanchez says. “You really don’t want to step on anyone’s toes.”

Just a day after his arrival in the majors, Sanchez was in the Blue Jays bullpen against the Red Sox, listening to the phone ring over and over as bullpen coach Bob Stanley communicated with the Jays’ dugout. In the minors, pitchers have an idea of when they might be summoned, based on pitch limits and how long it’s been since they last threw. But winning takes precedence over everything in The Show. You never know when your number might be called. “Every time the phone rang, I literally jumped out of my seat—I’m so nervous,” Sanchez says. “The other guys are like, ‘Whoa, this kid’s super amped.’” With the Blue Jays up by one, Sanchez entered in the seventh inning, tasked with protecting the lead against the heart of the Red Sox order: Dustin Pedroia, David Ortiz and Mike Napoli, who have 36 seasons and over 650 home runs between them. “I just told myself to pretend that there’s nobody in the box,” Sanchez says. “I had to get over the fact that I’m facing these guys I’ve watched play my entire life.” He got all three to fly out.

Meanwhile, Stroman was having his own brushes with characters he’d only seen on TV. One night last August, he went to Toronto’s upscale Barberian’s Steak House and ran into Detroit Tigers outfielder Torii Hunter, in town for a weekend series. Stroman went up to introduce himself as a fan, not as a contemporary. “Oh, what’s up Stro show?” Hunter said. “Your stuff is downright nasty.”

During that same series, Cy Young winner David Price sent Stroman a direct message on Twitter saying he wanted to meet up. On the Sunday morning, just hours before Price threw six innings of four-run ball against the Jays, the pair sat in the tunnel at Rogers Centre and talked for 20 minutes about how Price approaches the game, what he throws in certain situations and how he attacks certain hitters. Stroman sat and listened, feeling chills run up his spine as he got a personal lesson from one of his favourite pitchers. He wrote down much of what Price told him, and still texts the Tigers ace every now and then to ask him about anything from pitch grips to mental preparation.

Stroman’s most valued piece of advice came later in the year, when he was invited out to a dinner with some Blue Jays and Orioles. Adam Jones, the centre-fielder who played a key role in Baltimore’s 2014 run to the post-season, sat next to him and spent most of the night imparting wisdom he’s gained over nine seasons in the majors. “Stro, some people are going to fight it and be against it, but you have to always remain yourself. No matter what,” Jones told him. “Don’t let anybody say anything or do anything to affect that. Through it all, you have to remain yourself.” Stroman had spent much of his rookie season trying to tone down his exuberant personality, talking less, laughing less and celebrating less to be respectful of baseball’s unwritten code for rookies, which demands that they don’t draw too much attention to themselves. “You can’t be too flamboyant or flashy or outspoken or loud,” Stroman says, “and I’m kind of all of those things. It’s tough.”

As one of Toronto’s brightest young stars, he had a bevy of voices on the team and its management whispering in his ear about how to behave. He did everything he could to please them, but Jones’s advice reminded him that what made him succeed and what got him to that level was being himself, and that if he changed who he was, he’d risk losing it all. “I learned so much from all these guys. When they reach out to you and bring you into the circle, it’s so cool,” Stroman says. “That these guys who have been in the league for that long know who you are—that’s still so nuts to me.”

The monotonous days of spring training can blend together, especially in a place as ordinary as Palm Harbor, where Sanchez and Stroman are relaxing on a February afternoon, a few days after their famous night at WWE Raw, and a couple weeks before Stroman’s season would end before it started. They live in on one of those cul-de-sacs where all the houses are identical—white-and-brown two-storeys running up and down a street lined with tall, billowing elms. Ballplayers like this neighbourhood because it’s close to both the ballpark and the beach. Ricky Romero lives down the street; Casey Janssen did, too, until he left as a free agent. Inside the house, wearing T-shirts and sweatpants, Stroman and Sanchez lounge on the living-room sofa, watching MTV and ESPN as they kill time between now and the regular season. Sanchez’s phone buzzes as he texts friends back in Barstow. Stroman Instagrams a picture of himself looking contemplative in a Jays hat, captioned simply, “Out here.” Soon, a late-afternoon nap, then maybe a bite to eat. There’s really not a lot to do.

Suddenly ESPN comes back from commercial to a shot of Florida Auto Exchange Stadium in Dunedin, where the network’s crew spent the morning collecting film and sound bites for a spring-training report on the Jays. “Oh, shoot, turn that up, son,” Sanchez says to Stroman, who obliges and lays back as the pair catch up on what’s being said about the lives they live. “Stroman took really good steps, Sanchez was great when he came up,” says Blue Jays starter R.A. Dickey, answering yet another question about the Jays rotation. “They’ll be big pieces for us this year.”

Not two weeks after Dickey said that, Stroman was lost for the season, and the role Sanchez was to play became, if not bigger, then monumentally more crucial. The rookie was dominant out of the bullpen in 2014, with a 1.09 ERA in 33 major league innings, using a 97-mph fastball and a devastating 81-mph curve with incredible movement to take over as closer late in the season. This year, if he makes the Blue Jays rotation, he’ll use a nasty little low-90s changeup as well, and be counted on to fill many of the innings his best friend won’t be able to pitch. As if he needed reminding, the broadcast noted how arms like Sanchez and Norris could decide the team’s fate, even more than high-profile additions Russell Martin, Josh Donaldson and Michael Saunders. “As we all know,” the analyst says, “the Blue Jays haven’t been to the playoffs since 1993.”

“Yo, 1993? That’s like, what, 22 years? That stat is ridiculous,” Sanchez says, getting a nod from Stroman and running his hand through his hair. “Dang, son. We gotta change that.”

Photography: Michelle Prata; Dan Hamilton/USA Today Sports; Nathan Denette/CP