TORONTO – The acrid stench hit Ross Atkins immediately as he approached the small apartment Marco Scutaro and Willy Valera shared in the summer of 1996 in Columbus, Ga. Despite lacking most basic cooking utensils, the two 19-year-old infielders had tried to prepare some chicken for themselves and their arriving A-ball Red Stixx teammate. The previous day, Atkins noticed Scutaro and Valera on the sidewalk as he drove to the ballpark. They were walking the four kilometres from their place to the field in the draining 40 C heat. The 22-year-old right-hander invited them into his Ford Ranger, later offered them a ride the next day, too, and they planned to eat together before heading off to work. Good plan, only the charred remains of lunch filled the unit with a thick smoke that billowed out into the hallway. The door was open when Atkins arrived, and while Scutaro and Valera had things under control, their meal wasn’t the least bit edible.

"I’m like, ‘Let’s go eat today, and we’ll figure this out tomorrow,’" Atkins recalls. "I took them to Applebee’s and they said, ‘This is a restaurant? We thought it was a clothing store.’ Then they opened the menu and were like, ‘There are pictures of the food? All we have to do is point?’ That’s when I was like, ‘God, there’s got to be a better way of transitioning Latin guys.’"

Atkins, born in Greensboro, N.C., but raised in Miami where he picked up some Spanish from friends in the neighbourhood, had some ideas, ones he shared with Mark Shapiro, then director of minor-league operations for the Cleveland Indians, and Bud Black, a special assistant to Tribe GM John Hart. Though Atkins had a solid season in the summer of ’96, posting a 3.93 ERA over 169.2 innings, it was his intellect, not his arm, that left a lasting impression. Shapiro remembers early on thinking of Atkins as a person "that someday I’d like to work with if I ever had a chance to run an organization."

Someday came in 2000, when Atkins retired after his development plateaued during two seasons at double-A Akron. A job as a pitching coach and working with Danys Baez as an English instructor and translator during his transition from Cuba to the United States followed, the first steps on a career path that has taken him to general manager of the Toronto Blue Jays.

"The environment in Cleveland was one where it was all about development," says Atkins. "Mark was a player-development leader, but he was also a staff-development leader in the front office. It created this culture where you were exposed to everything and you were given unbelievable opportunity to lead, a culture of empowerment.

"What I focus on is how do we create the best possible environment for our players to not only get better, but to really want to be here, and to do something as part of a team and part of an organization so we look up at the end of this year, two years, three years and people want to be Toronto Blue Jays, because of the environment, because of the resources and because of the selflessness that our culture creates."

***

Alex Gonzalez and Shannon Stewart, Blue Jays teammates in the late 1990s and early 2000s, were among the many future big-leaguers with ties to Ross Atkins’ old district in Miami. (J.P. Moczulski/CP)

Atkins first started playing baseball at age five, shortly after his family moved to Miami so his father Lane, who worked in advertising, could pursue a job opportunity. They lived near the University of Miami and at night, when he and older brother Harris would move from playing wiffleball to basketball because there was a lamp by their backyard hoop, they could hear the public address announcements from the baseball stadium. Kids in the neighbourhood dreamed of growing up to play for the Hurricanes, who ruled the local baseball scene with the arrival of the Marlins still a long ways away. And boy could the boys in the area play. Mike Lowell lived around the corner and was a close friend. Alex Rodriguez, Shannon Stewart, Alex Gonzalez, Raul Ibanez, Doug Mientkiewicz and Eli Marrero were all in the same district and within a couple of years of Atkins. They played on the same summer teams at various points. "Miami baseball was really good," he understates. "I had love and passion for it – I wanted to do nothing else but play some type of game in the backyard – but I didn’t really stand out. I was fine."

At Coral Gables High School, Atkins pitched and also played shortstop, first base and outfield, but didn’t get drafted. He didn’t expect to, either. Though he wanted to play baseball as long as he could, he knew he needed to make his education a priority. The Hurricanes offered him a spot on the team – his mother Ellen worked at the University of Miami and that would have helped with his tuition costs – but instead he chose Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., where he could pursue an economics degree while playing baseball. Atkins’ uncle, Dave Odom, coached the basketball program that developed Tim Duncan at the school, he was tight with his cousins in the area, "and selfishly, I don’t like to admit it, I thought I’d play right away."

Atkins did enough during his junior year to get selected by the Florida Marlins in the 69th round of the 1994 draft, but he didn’t even consider signing, choosing instead to focus on his degree. By that point he recognized how unlikely a professional career was, and was considering other avenues to remain in sports, things like marketing, branding, management, training, or building a small business off his baseball background. But a year later, as he was cocooned while working on his senior economics thesis, his mother phoned him.

"She said, ‘Hey, the Cleveland Indians just called you, they drafted you,’" recalls Atkins, who this time went in the 38th round. "I was like, ‘Really? OK, cool, that’s awesome, but I kind of have to finish this thesis.’ Kasey McKeon (the selecting scout) then calls me and I said, ‘Can I finish this thesis? I’ll be there soon.’ He’s like, ‘No, you can’t. Dude, do you want to play?’ I said, ‘I do, but I would love to be able to be done with school.’ I was paying tuition, my mom and dad were doing everything they could, I had a little bit of scholarship, I’d taken out student loans, so I was like, ‘How about you guys just pay for that?’ McKeon was like, ‘Dude, do you want to play?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’"

McKeon had plenty on his plate. In that same draft, he also selected first-rounder David Miller, second-rounder Sean Casey, 17th-rounder Terry Harvey and 23rd-rounder Mark Budzinski and had to sign them all. They agreed to meet at a McDonald’s near the airport in Greensboro to get the contract signed, and Atkins drove up in the same Ford Ranger he’d be driving in Columbus, Ga. "As I’m pulling into the lot this guy backs up and bumps into my car," he says. "Kasey comes flying out of nowhere and he’s like, ‘What are you doing?’ to the guy, totally defending me, gets in the guy’s face. He’s just a fiery, awesome guy and that was our introduction. And then we signed a contract at McDonald’s for a pair of shoes."

The signing bonus was actually for the minimum $1,000, which Atkins considered "a lot of money" at the time. He immediately reported to low-A Watertown of the New York-Penn League, receiving permission from the dean at Wake Forest and his professor to complete his thesis via remote while playing. Atkins graduated as a member of the Atlantic Coast Conference honour roll. "I woke up thinking about sports all the time, so I aspired to be in sports," he says, "but I wanted a business background of some kind."

***

In the summer of 1999, Bud Black stopped to chat with Atkins and asked him what he planned to do after baseball. The season, the right-hander’s second at double-A Akron, wasn’t going well. He finished with a 5.77 ERA in 33 games, seven of them starts, and his WHIP was up to an unsightly 1.569 largely because of his 4.8 walks per nine innings. During his first year in Akron, he at least enjoyed a stretch where he pitched well out of the bullpen, finishing with a 4.19 ERA in 40 games, five of them starts. But not in ’99 and he came to understand that "if I was going to persevere, this was going to be uphill."

"I started to try all different kinds of things with my delivery," Atkins continues. "Once that happens, you make the decision that you’re going to do it forever, independent ball, whatever, until you find it, or you say, ‘OK, I’m going to move on.’ And I was in that phase when Bud Black asked, ‘What do you want to do after baseball?’"

Atkins had a firm grasp of what was holding him back. He always threw max effort, which kept him from learning how to command the ball. As a result, once the competition improved, he spun his wheels. "I was pretty good at pitching backwards, I could throw a changeup in a 3-1 count, which for an A-ball pitcher is relatively advanced," he says, "but I couldn’t command my fastball enough and couldn’t develop a good enough breaking ball."

Black’s question was strategic. The Indians recognized the same thing, and had taken a liking to Atkins. His grasp on a roster spot was slipping away, but they didn’t want to lose him, either, and the visit was a way to shift the conversation.

"I was like, ‘Dude, I want to play, but when I think about opportunities in baseball, I think about helping Latin players, which I do, but I wonder if there’s a way to do it more systematically. Can you create a role that they’re focused on those transitions, like a university does with orientations?’" recalls Atkins.

The Indians were interested, but Atkins wasn’t fully ready to give up. After the season, he headed to Barcelona to really polish his Spanish, which he studied at Wake Forest and practised regularly in the minors with Scutaro, who concurrently worked on his English with Atkins. During the days, he cleaned the bottom of racing sailboats, gruelling work smoothing out the sides to help increase speed in the water. At night he worked out with a professional baseball team predominantly made up of older Cuban players. They offered him a contract but he turned it down because, "I had to go back and see if there was something there."

At spring training in 2000, he experimented with different arm angles, changing the tempo in his delivery, trying anything he could think of to become more fluid and powerful. The harder he tried, the worse he pitched, and he was ready to give up. "I had these two contrasting opinions," Atkins remembers. "Marco Scutaro was looking at me like I had lost my mind. He’s like, ‘What are you doing? I’ve seen you, you’re competitive, you can do this.’ People from home were saying, ‘You have a college degree, is going through another minor-league season where you’re an older guy, you’re not in the rotation and you’re making $5,000 a year and have to scratch and claw every off-season what’s best for you?’ My awareness of the world I was in was telling me the odds were stacked so heavily against me that it was best to try something else.

"I walked into Mark’s office and said, ‘Listen man, I’m done. I want to talk to you about a career in baseball.’ And he said, ‘When do you want to start?’"

***

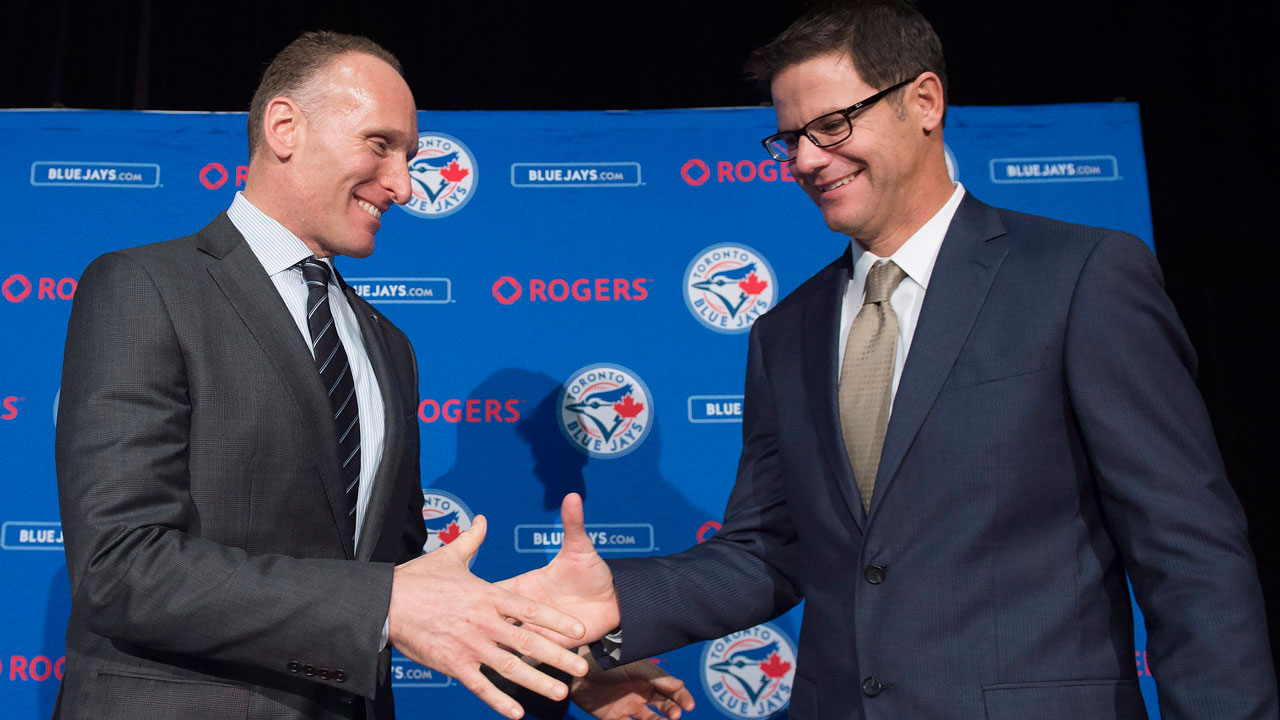

President Mark Shapiro, left, shakes hands with Ross Atkins during a press conference in December introducing the new Toronto Blue Jays GM. (Nathan Denette/CP)

Atkins spent one season in coaching before moving to the front office in 2001 as the assistant farm director to John Farrell. Three years later, he took over as Cleveland’s director of Latin American operations and then became director of player development in 2007. He served in that role until being named vice-president of player personnel after the 2014 season, where he worked in everything from contract negotiations and salary arbitration to trade talks.

"Areas you were passionate about and you wanted to be creative and wanted to learn more about, I’ve always been empowered to do," Atkins says of his experience with the Indians. "Because of that I’m able to connect with someone handling arbitration. I’m able to connect with people that are delving into analytics and building decision-making models and finding the most advanced resources for us. I’m able to connect with people in high performance. I have a pretty good idea of what their challenges are and what they’re facing having been exposed to all those areas of a major-league team."

Speculation within the industry was always that he’d join the Blue Jays in some capacity once Shapiro took over as the club’s president and CEO. But then Alex Anthopoulos’s unexpected departure created an opening in the general manager’s chair.

Atkins replaced the reigning executive of the year and inherited the defending American League East champions, with a core returning largely intact. The first impact move under his watch came over the weekend, when reliever Drew Storen was acquired from the Washington Nationals for left-fielder Ben Revere. On Wednesday, the Blue Jays hired Gil Kim as their new director of player development. Pivotal decisions with the potential to define his tenure loom in the expiring contracts of Jose Bautista and Edwin Encarnacion. A farm system left with a worrying talent gap between the lower levels and the big-leagues poses a significant challenge.

So too does the trend toward larger, more diverse front offices, in theory creating more intellectual capital for each club to work with and perhaps eroding previously exploited advantages. More and more teams are doing the same things.

"When things skew heavier one way, they’re going to skew too far at one point," says Atkins. "Understanding how to balance things and how to weigh things is the way you’re going to beat other teams. Opportunities are always going to exist. It’s not about whether front offices are getting smarter, it’s always going to be about finding inefficiencies. If you look around and there are nine people thinking that way, not just me, and they’re not just looking at what’s in front of me today, how do I get that off my list, but they’re all breathing with a level of ownership, then you can beat people. It takes that level of innovation on every front."

Success in his new role will come from staying ahead of the curve and keeping the Blue Jays from falling back into the two decades of misery that preceded last year’s AL East title. Unlike Scutaro and Valera that fateful day in Georgia, this franchise doesn’t need to be taken from a smoke-filled room, it needs Atkins to keep moving it away from the one it just escaped.