This piece originally appeared in the May 26, 2014 edition of Sportsnet Magazine. Photography by KC Armstrong.

THE TATTOO COVERS his entire left shoulder and bicep. Feathered angel wings spread out from either side of a cross, bleeding into a dark background marked with stars. A dove sits on a halo atop the cross; a banner reading “My #1 Fan” wraps around it. Further down, closer to his elbow, in cursive: “Where there is love, there is life.” And right in the middle, stretching over the bottom of the cross, reads “RIP Grandma.” The “I” is a bowling pin. She always loved to bowl.

And she was always his No. 1 fan. When Marcus Stroman was 20 years old and starring for the Duke Blue Devils, his grandmother, Gloria Major, would drive from Long Island, N.Y., to North Carolina to see him play. Since high school she had gone to every game she could, even in the frigid cold, always sitting in the first row, wrapped in a blanket.

When Stroman was a junior and focused on impressing major-league scouts in his draft year, he got a call from his parents. They’d held off telling him as long as they could so it wouldn’t distract him, but they felt he needed to know his grandmother had cancer. Stroman was devastated, but what was worse was that his parents were telling him to stay at school, nine hours away, and focus on getting drafted. Stroman argued with his parents for days. He begged them to give him the money to get on a bus, a plane, whatever, and come home. Please buy me a ticket, mom. Please.

Eventually they did, and Stroman went home to see his grandmother like he’d never seen her before. She’d lost weight. She looked pale. She was weak. But the doctors said she was getting better, and Gloria had already bought a ticket for Duke’s season opener against Texas in three months and couldn’t wait to get out of the hospital and watch her grandson pitch. Stroman went back to school the next week, and two days later Gloria Major died. Stroman was in his room by himself when he got the news. He got off the phone and sat on his bed bawling for longer than he can remember. The funeral came soon after and then the tattoo—the most intricate piece he’d ever gotten—which would anchor the sleeve that now covers his left arm.

“Once I got the tattoo I was like, ‘OK, let’s do this. Let’s do this for her,’” Stroman said in April before being called up to the majors. “I never cry. My grandma’s passing was the last time I cried. But when I get that call to go to the majors, I think I might cry. Because it’ll be for her. Everything will have been for her.”

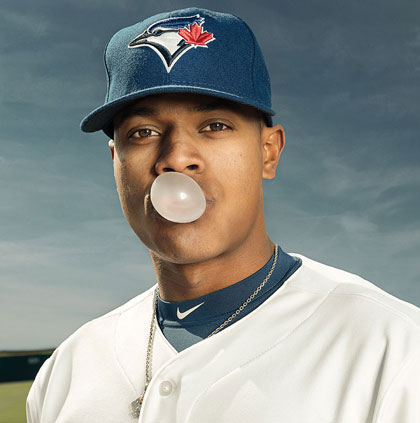

This is Marcus Stroman. Straight out of New York; playing for his family; burning with desire. An undersized pitcher with wicked stuff who’s been written off more times than he can remember but keeps going. He’s the future of the Toronto Blue Jays and the most exciting prospect the club has had since Roy Halladay. A right-hander who could be a front-line starter at best or a lights-out closer at worst. Everything he’s done for the past two decades has been working toward this moment. On the mountain climb that is succeeding in the major leagues, Stroman has one hand firmly gripped on the ledge of the peak. Now he just has to pull himself up.

—–

THE TATTOO IS on the inside of his left arm. One of his mom’s green eyes stares warmly out from just below his elbow with “La Familia” arching overtop the eyelashes. His dad’s detective badge—No. 1278—sits just beneath it. Further down, on the inside of his wrist, it says “Daddy’s gift” in cursive. On the outside, “Momma’s boy.” He’s always done it all for his family.

But it hasn’t always been easy. When he was in the fifth grade in Medford, Long Island, Stroman’s parents separated and his father, Earl, a Suffolk County detective, moved to a house about a mile away. Stroman already had a strained relationship with his father, who made him run parachute sprints up hills and push weighted sleds from the time he was six years old. Stroman hated it. Earl would make his son read the newspaper regularly and gave him reading comprehension tests based on what was in the news. If Stroman got any answers wrong he’d have to start over again. Sometimes, Earl would convene full-on living-room sparring contests between Stroman and his older sister, Sabria, when they were both in karate.

“My dad pushed me to the edge. It was hard. It really took a lot out of me,” Stroman says. “But that’s how my dad’s wired. He wanted to be successful in life and he wanted the same for his kids. He hated failure. If I ever failed at something there was no discussion—it was back to the batting cage or back to working out.”

Basketball was Stroman’s first love (he figures he could’ve played for a low Div. I or Ivy League school if he’d pursued it) but by the 12th grade, baseball had become his focus, and although he was drafted in the 18th round by the Washington Nationals and offered $400,000 to sign with the club, Stroman chose to take a full scholarship to Duke University instead. Before he even arrived at the school, followers of Duke athletics were writing him off, believing he didn’t have the stature or the mettle to play Div. I baseball. Stroman would search his name on the Internet and print out the comments, taping them to his wall and reading them before he went to work out. The one he remembers best is the guy who said he wouldn’t be able to line the fields at Duke.

The criticism was apt. Stroman never did line Duke’s fields. What he did do was win the Atlantic Coast Conference Freshman of the Year award, making five starts on the mound while also playing 44 of Duke’s 56 games at second base. His performance earned him an invitation to play in the Cape Cod Baseball League that summer along with the top talent in the country, where he closed for the Orleans Firebirds and didn’t allow a run in 27 innings. That was the summer, spent playing on high-school diamonds with packed stands and dozens of MLB scouts regularly in attendance, when Stroman knew he could play baseball for a living.

He spent his next two years continuing to play two positions at Duke. His 12.64 K/9 in 2011 was the second-highest in the NCAA; his 12.49 in 2012 was third. He was Duke’s Friday night starter (the ace of the pitching staff) and averaged seven innings a start, blowing 95-mph fastballs past overmatched hitters before getting them to chase spinning sliders in the dirt. Scouts told him he was a first-to-fifth-round talent in the MLB draft and that his best chance of making the majors was as a reliever. But he still wanted to start.

The Blue Jays drafted him 22nd overall in 2012 and started him in Vancouver before quickly moving him to double-A New Hampshire. They had him work on his changeup and his cutter, complementary pitches to his reliable fastball and slider. Many thought he could reach Toronto by the end of the season but in late August, Stroman tested positive for methylhexaneamine, a banned stimulant he ingested through an over-the-counter pre-workout supplement. Had Stroman been in the majors, where the players are unionized and drug policies are collectively bargained, his punishment would have been six unannounced tests over the 12 months following the violation. But in the minor leagues, the rules are stiffer and Stroman had to sit for 50 games bridging the 2012 and 2013 seasons.

In a strange way, it was a positive development for him. He remained in extended spring training in Dunedin while he served his suspension at the beginning of 2013, waking up at 6 a.m. every day to go to the ballpark and work on his changeup. He developed the pitch into a nasty, fading off-speed weapon that can be hard to pick up because he throws it with the same arm movement as his fastball. Stroman took the pitch back to New Hampshire after serving his suspension and put up a 3.30 ERA over 20 starts, striking out 129 in just 111.2 innings. He had only one truly bad outing, a seven-hit, seven-run, single-inning start against the Portland Sea Dogs. He allowed two runs or less in 16 of his 19 others and finished the season with a near-perfect performance against Las Vegas when he struck out 11 over eight innings and allowed just two baserunners.

Even the blowout against Portland ended up being helpful to Stroman’s development. The following day he came out of the dugout for batting practice and saw Pedro Martinez talking to some players in the outfield. The former Expos and Red Sox star was Stroman’s favourite pitcher growing up. He watched endless video of Martinez, studying his delivery and how he was able to pitch with tremendous velocity despite a slight stature. Stroman ran out to him with a ball to sign and Martinez immediately recognized him and said that he’d seen him pitch the night before. Stroman was a little crushed—it was the worst start of his career.

“And then he told me he was impressed with my stuff. And I was like, what? I got hammered,” Stroman says. “But he said he thought I pitched well and he had all this advice for me.”

Martinez told Stroman he was relying too much on specific zones and that he had to change the batter’s eye level more often. He told him not to be afraid to pitch inside. If you hit the batter, you hit the batter. It’s more important to take control of the inside of the plate. Martinez told him that even as a smaller pitcher he couldn’t be afraid to throw his pitches up in the zone, because if he didn’t, batters could key in on his location. They talked for 30 minutes and Stroman sprinted to the clubhouse as soon as they finished and madly scribbled down everything Martinez had told him. He looks at the notes before every start.

His final stop before the bigs was Buffalo, pitching for the triple-A Bisons, still overpowering hitters and fooling them with his off-speed, and looking like he was too advanced for yet another level. He struck out 36 over 26 innings and allowed just five earned runs in five starts. Two of those starts were pitched in sub-freezing temperatures, which did little to hamper Stroman’s velocity or the movement on his pitches. He was everything he said he would be. And what’s remarkable about Stroman is he’s still in his infancy as a starting pitcher; we may be seeing just the beginning of his potential.

“His stuff is ready for the majors, absolutely. And he’s still improving,” Bisons pitching coach Randy St. Claire says. “Sometimes he just tries to do too much. Instead of attacking a hitter, he’ll try to back-door him and make him look foolish. But if he realizes that all he has to do is locate his quality pitches and go after hitters, he’s going to absolutely roll. When your stuff is that good you don’t have to be so tricky.”

So that’s the criticism against Marcus Stroman: He tries to be too good. Where an average pitcher would get ahead 0-2 and look to induce weak ground-ball contact with a fastball down and in, Stroman wants to punch the guy out. He wants to make him swing where the ball no longer is or watch in vain as a breaking pitch drops into the very edge of the zone for a called third strike. He doesn’t want to be good; he wants to be great. He wants to be perfect.

That mindset, no doubt, comes from his dad. It comes from sprinting up hills as a child and missing all your class trips because your dad wants you to stay home and spend more time in the batting cages. Earl is more encouraging and supportive now. Calmer, mellower. Stroman describes their relationship as brotherly. They joke about how hard Earl used to be on him. And he thinks about his dad every time he takes the mound. “None of my success happens if I don’t have my upbringing,” Stroman says. “I’m so grateful. My dad made me a better person. He taught me I can achieve anything.”

—–

THE TATTOO STRETCHES across the right side of his chest. “Height Doesn’t Measure Heart” in large type, the first letter of each word bolded and larger than the rest. Beneath it, a Martin Luther King Jr. quotation: “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.” Stroman has always believed he could prove everyone wrong.

Or maybe just prove himself right. Stroman is just five-foot-eight, well below the typical height of an MLB pitcher. Most baseball people look at a kid like that and immediately think reliever. Stroman staunchly asserts that he can start in the majors and he’s proven he can do it at every step, from college to triple-A. But no matter how hard he works, how many batters he strikes out and how many dangerous pitches he adds to his repertoire, there are still those who say Stroman will never start at the highest level. Many scouts still believe he’s destined for the bullpen.

That’s because baseball is less than receptive to new ideas, one of them being that short guys can be starters. Over the last 30 years, 2,083 pitchers have started a game in the major leagues. Just four of them have been shorter than 5’9 and none of those four went on to make more than eight starts. You can pull the lens back even further to 1950 (a sample of 3,493 starters) and increase the height range to 5’9 but you’ll find there’s only 26 pitchers of that height or shorter who have made at least 10 major league starts. It just doesn’t happen.

You have to go back to the late 70’s to find a 5’8 starter who had a long career. That was Fred Norman, who had four seasons of 30 starts or more over his 16-year tenure and finished his time in the game with 104 wins and a 3.81 ERA. Past Norman, you can find only a couple players who were 5’9 and able to start regularly. Tom Gordon made 203 starts over the first ten seasons of his career in the early 90’s before transitioning to the bullpen. He won 73 games and had a 4.40 ERA as a starter. Harvey Haddix, a 5’9 left-hander, made 286 starts over his career and even led the National League in ERA one year. Of course, that season was 1957—he was finished as a starter by 1962—when the average height of major leaguers was much shorter.

The worry is that such a short body won’t be able to get the necessary downward plane on a fastball to make it difficult to hit. Instead of the pitch coming in from the mound moving down toward the hitter, it comes in moving flat, which makes it easier to get under and turn around for a home run. It’s believed that batters also have more time to see the pitch, because shorter starters can’t extend as far forward on the mound as taller ones, meaning they release the ball from further back. It’s also speculated that a smaller body won’t hold up as well to the rigours of a 200-inning season. Taller pitchers have longer limbs, which allow them to apply force behind their pitches simply through extended, smooth mechanics. But shorter pitchers must use more muscle and harsh movement in their deliveries in order to generate velocity, which could lead to injury or exhaustion when performed 100 times every five days for six months.

The downward plane argument at least has science behind it, but it’s harder to get a bead on the durability issue because so few pitchers of Stroman’s stature have ever had the opportunity to start consistently. There simply isn’t much data to work with, especially over the past two decades, during which athletes have improved their physicality dramatically and average pitch velocities have crept upwards. We just don’t know what would happen if someone who’s five-foot-eight were given 32 starts a year in today’s game.

What we do know about Stroman is that his fastball and slider are exceptional pitches, while his changeup, curveball and cutter are all major-league average, if not better. He throws all five for strikes on either side of the plate and feels comfortable using them in any count. He has terrific command and walked just 43 batters in 157 minor-league innings. The life on his fastball is so electric that scouts have argued over whether the pitch is a riser (seemingly moving up as it nears the plate) or a runner (moving to Stroman’s right as it reaches the plate) because it often appears to do both. You won’t find many pitchers in the major leagues who can do all those things, no matter how tall they are.

So if anyone could break the starters-must-be-tall belief, why not Stroman? Why not a pitcher who has absolutely everything you look for in a successful major-leaguer—including great makeup and confident mound presence—except for inches? “People think there’s a cookie cutter way for guys to be,” Stroman says. “And because I don’t look like that they write me off immediately. I’ve battled it my whole life.”

Stroman’s height is something he cannot control, so he focuses on the things he can. He works out tirelessly to strengthen his legs and his core, which is where he generates his velocity. He stretches every day, focusing on flexibility in his pitching arm, which has allowed him to get through his entire baseball career without major injury.

On the mound, Stroman manages his height disadvantage by simply being a better pitcher. He hits his spots and doesn’t miss the catcher’s glove. He keeps his fastball down in the strike zone, mixing the speed and location of his secondary pitches to keep batters off balance. He works quickly, readying himself to throw his next pitch almost immediately after getting the ball back from the catcher, which makes hitters uncomfortable.

Still, Stroman will likely spend his entire career combating the assertion that he’s too short to start. When he succeeds his height will never be mentioned. But when he fails, as all ballplayers do, it’s likely the first thing critics will cite. “Even if I have three or four good starts, as soon as I have that bad one people are going to say ‘Oh, look, there it is—he can’t start,’” Stroman says. “But there’s got to be a first person to do everything. And I fully believe I’m going to be that person.”

—–

THE TATTOO IS on the outside of his left forearm. “Dreamchaser” in cursive lettering winds its way toward the wrist. A bit higher, near the inside of the bicep, he has the MLB logo. He’s always been clear about his intentions.

There is nothing shy about Marcus Stroman and nothing dim either. He’s intelligent and thoughtful; quick with an opinion and confident with his words. But in a lot of ways he’s still just a kid—albeit one armed with an excess of disposable income who throws a ball for a living. His primary areas of interest outside baseball are buying clothes, expanding his sneaker collection, and his car, a 2013 Audi S6 he bought with bonus money and quickly pimped out with a matte charcoal wrap and aftermarket rims. Before Stroman spent a day in the majors he already looked the part. On a recent cold off-day afternoon in Buffalo, his primary concern was finding a barbershop somewhere in upstate New York where he could get his hair cut the way he likes it—a tape-up around the sides and an edge-up along the hairline done with a straight-edge razor. He doesn’t mess with that electric razor stuff.

This is the lifestyle his small measure of professional success so far has afforded him. He always liked expensive jeans and custom cars but never had the funds to get them. Now he does. He always loved sneaker stores but could never leave with any product under his arm. Now he can, even though his mom still loses it every time he comes home with a new pair to be stored away in the room he grew up in, which is beginning to resemble a Foot Locker warehouse.

But Stroman refuses to spoil only himself. One of the first things he did with his $1.8-million signing bonus was pay off his mom’s mortgage. Then came a shiny new Rolex for dad—“WITHOUT YOU, NOTHING WAS POSSIBLE! LOVE, MARCUS” engraved on the back. When his sister got engaged he arranged a full “Say Yes to the Dress” event at Kleinfeld Bridal in Manhattan and bought the wedding dress she chose. “I never want to look back and say, ‘I should have done this’ or ‘I should have done that.’ I hate regret so much,” Stroman says. “My parents spent who knows how much money sending me to tournaments, paying for this, paying for that. So I really want to make it to the next level—solely so I can give back to them.”

The next level came in May. Stroman was called up to bolster a Blue Jays bullpen that was in dire need of reinforcements, before quickly being returned to the minor leagues to refocus on being a starter. His promotion came about well before the Blue Jays would have preferred and when Stroman was in Toronto mopping up late-game messes he made no reservations about his desire to be a starter. Now, he’s back on that path. Back in Buffalo with its inclement weather and its minor league crowds and its pot hole laden roads that make him cringe every time his beloved car hits a bump. Now he’s back to waiting.

Of course, ever since he turned professional he’s been doing things bigger, better and faster than anyone could have expected. The next time he takes a major league mound will ideally be as a starter. He’ll take that mound with a swagger and six sticks of Orbitz sweet mint wedged in his lower lip. He’ll touch his grandmother’s tattoo on his left arm at the start of every inning, just to know she’s there with him. And then he’ll get to work. “I’ll be pretty emotional before that first start, just because I know my grandmother would’ve been the first one there to watch me,” Stroman says. “She would’ve been on that first flight. She wouldn’t have missed it for anything. Not for the world.”

In that moment, all the talk will make no difference—not to him and not to us. Stroman plans to go as far as his legs will carry him. Whether he’ll be successful, he can’t tell you. Stroman doesn’t make promises. He only makes believers.