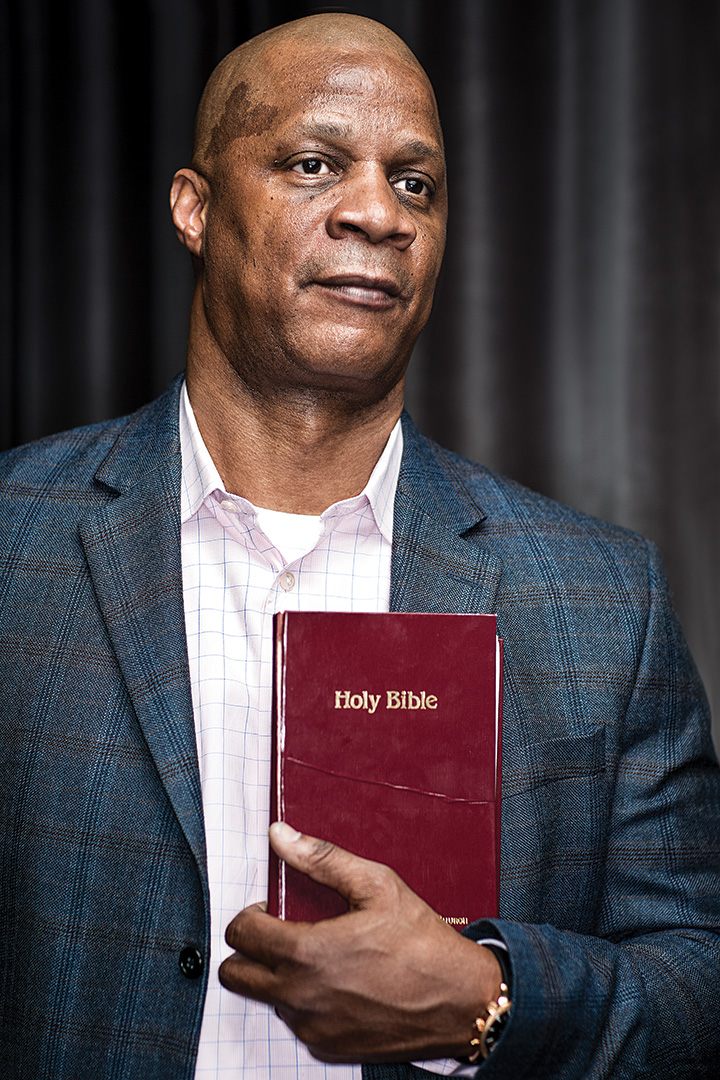

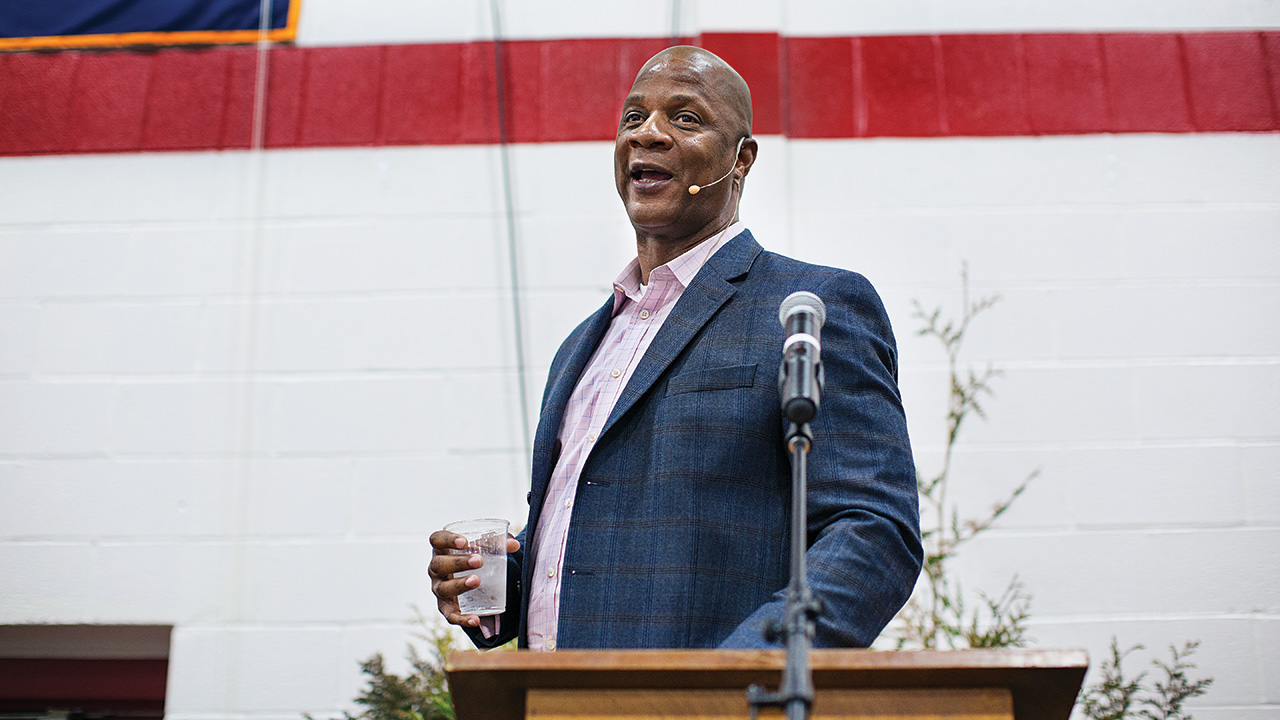

arryl Strawberry paces back and forth on a creaky stage barely bigger than a batter’s box. He exhales, then looks up at the ceiling of the Mount Calvary Christian School gym. “He’s so loving,” Strawberry says, smiling. “He is so wonderful.” Behind him hang decades-old banners celebrating volleyball and basketball championships. An “Amen, brother” comes from somewhere in this crowd of 450, followed by a bunch of “mmm-hmm”s. Strawberry is wearing a dark-blue suit jacket and pink button-up, and his arms are going. He comes to a stop on the stage. “God is the only reason why I’m standing today,” he says, looking over his audience. “Not because of anything I’ve done.” On the wooden podium in front of the eight-time all-star and four-time World Series champion—as he’ll remind the crowd several times this evening—there are no notes. He doesn’t need them to keep this audience spellbound for the next 47 minutes.

arryl Strawberry paces back and forth on a creaky stage barely bigger than a batter’s box. He exhales, then looks up at the ceiling of the Mount Calvary Christian School gym. “He’s so loving,” Strawberry says, smiling. “He is so wonderful.” Behind him hang decades-old banners celebrating volleyball and basketball championships. An “Amen, brother” comes from somewhere in this crowd of 450, followed by a bunch of “mmm-hmm”s. Strawberry is wearing a dark-blue suit jacket and pink button-up, and his arms are going. He comes to a stop on the stage. “God is the only reason why I’m standing today,” he says, looking over his audience. “Not because of anything I’ve done.” On the wooden podium in front of the eight-time all-star and four-time World Series champion—as he’ll remind the crowd several times this evening—there are no notes. He doesn’t need them to keep this audience spellbound for the next 47 minutes.

This highly anticipated speech is the main event of the spring banquet to benefit Cornerstone Youth Center, a religious hangout some 10 minutes away, here in Elizabethtown, Pa. (Last year, the banquet’s keynote speaker brought owls and snakes.) All the guests—Strawberry included—have just been treated to a dinner of chicken, canned corn and boiled green beans on plastic plates. Blue and orange Mets-coloured tablecloths adorn every table, each decorated with a handful of Styrofoam baseballs that’ve been dutifully cut in half by some volunteer, then sliced again at the top so a Darryl Strawberry baseball card could be wedged within. Tickets to tonight’s fundraiser were free.

Hands up if you’d be more surprised to find Darryl Strawberry in a church than a crack house. The last we heard of him, he’d thrown away what should have been a Hall of Fame career because he was a drugged- and boozed-up disaster. Cocaine forced Strawberry’s retirement in 2000 after Major League Baseball handed him a year-long suspension for failing yet another drug test, and then he faded out of public consciousness, unless you include here-we-go-again news reports of his subsequent screw-ups. The way his life was going—rehab, relapse, repeat—you had to figure that was the end of the story. And it is. Because Darryl Strawberry The Addict is dead. And so is Darryl Strawberry The Baseball Player, the one who played 17 MLB seasons, made more than $30 million and lost it all. Today, it’s Darryl Strawberry The Man of God, and you wouldn’t recognize him. He’s a 52-year-old ordained minister who doesn’t own a ball glove and prays before every meal. The man who tried so many times to reinvent himself, only to fall back into drugs and women and booze, swears this is his final reinvention. And, Minister Strawberry says, if he could do it all over, he never would have played baseball.

t doesn’t take a sociology degree to understand the power of sport, to know that a kid who grows up in a crime-riddled neighbourhood can sometimes find his way out on the sandlot or the court or the field. Darryl Strawberry grew up in South Central Los Angeles, where homegrown rapper Ice Cube says the first rule of survival is “Get yourself a gun.” But today, sitting in a hotel restaurant in Hershey, Pa.—yes, Strawberry in the land of chocolate; it’s perfect—wearing sneakers, jeans and a black Mizuno sweater, he looks like the product of an upper-middle-class upbringing. The only sign he didn’t grow up privileged are the braces that now line his bottom teeth. He downplays how bad it was in South Central’s Crenshaw District when he was a kid. “It wasn’t like Boyz n the Hood,” he says, grinning. But baseball, he admits, was the safe haven. All three Strawberry boys—Mike, Ronnie and Darryl, the youngest—found the game as little guys, watching their dad suit up in the post office league, then imitating the sweet cut of their pop, known on the field as Big Hank, before joining teams of their own. They were the highlight in Crenshaw. People from all over the neighbourhood gathered to watch the Strawberrys play. Coaches from all over L.A. recruited the brothers, trucked them around the city for games and practices. Teams were built around them. A coach named Mr. Anderson—the Strawberry boys claim they never knew his first name—saw the three playing on a sandlot and promptly started a team. “The Blacksocks,” Strawberry says, smiling. “That was cool.”

t doesn’t take a sociology degree to understand the power of sport, to know that a kid who grows up in a crime-riddled neighbourhood can sometimes find his way out on the sandlot or the court or the field. Darryl Strawberry grew up in South Central Los Angeles, where homegrown rapper Ice Cube says the first rule of survival is “Get yourself a gun.” But today, sitting in a hotel restaurant in Hershey, Pa.—yes, Strawberry in the land of chocolate; it’s perfect—wearing sneakers, jeans and a black Mizuno sweater, he looks like the product of an upper-middle-class upbringing. The only sign he didn’t grow up privileged are the braces that now line his bottom teeth. He downplays how bad it was in South Central’s Crenshaw District when he was a kid. “It wasn’t like Boyz n the Hood,” he says, grinning. But baseball, he admits, was the safe haven. All three Strawberry boys—Mike, Ronnie and Darryl, the youngest—found the game as little guys, watching their dad suit up in the post office league, then imitating the sweet cut of their pop, known on the field as Big Hank, before joining teams of their own. They were the highlight in Crenshaw. People from all over the neighbourhood gathered to watch the Strawberrys play. Coaches from all over L.A. recruited the brothers, trucked them around the city for games and practices. Teams were built around them. A coach named Mr. Anderson—the Strawberry boys claim they never knew his first name—saw the three playing on a sandlot and promptly started a team. “The Blacksocks,” Strawberry says, smiling. “That was cool.”

No Strawberry was more captivated by the game than the youngest. When he was 10, Darryl told everyone he was bound for the majors. He slept while clutching his baseball bat in the room he shared with Mike and Ronnie in the family’s three-bedroom brick home. “We’d be like, ‘What is wrong with you?'” Mike says, laughing. “His heart, though, was all about baseball.” The body caught up the summer after Grade 8, when Darryl grew four inches. The newly six-foot Strawberry ran like a blind baby deer on muscle relaxants, but his raw power was shocking. By the time he was a senior at Crenshaw High School, Strawberry was six-foot-four and a national sensation with an insanely fast bat and a looping swing, making headlines as the black Ted Williams, even if he didn’t know who that was. He pitched, played right field, hit .400 and had five home runs as a senior. “My gift,” he says, simply, “was baseball.” He seldom let go of his bat. “You gonna learn how to hit the ball a long way,” he’d tell that bat. It makes Strawberry laugh today, to remember how he’d talk to it. He laughs so hard he can barely get the words out: “We gonna do some great things.”

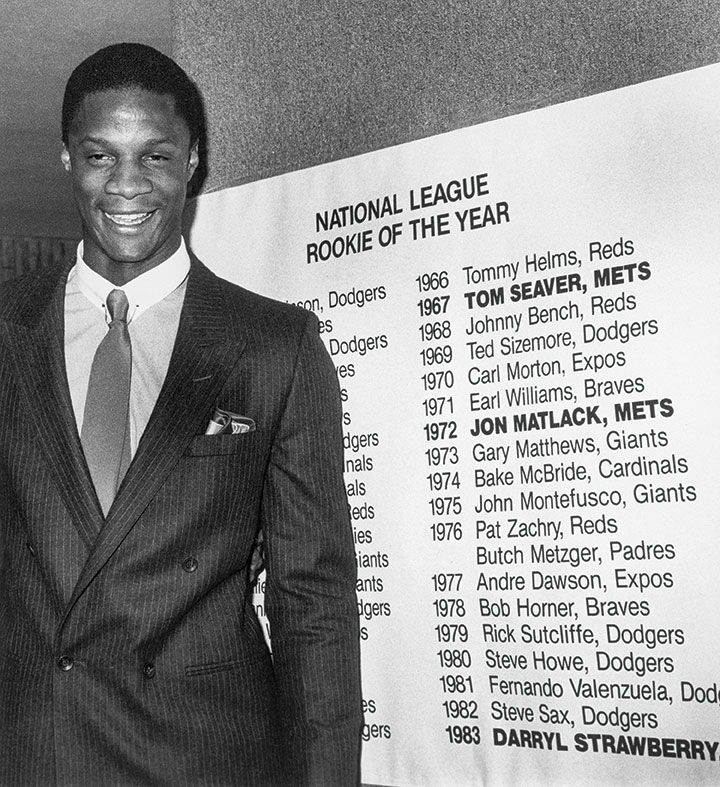

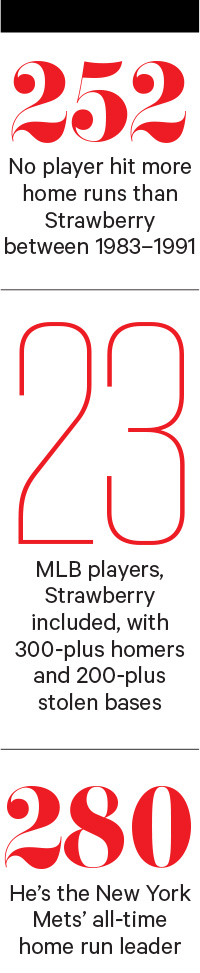

The expectation was beyond mere greatness when the New York Mets picked Strawberry, straight out of high school, first overall in the 1980 MLB amateur draft. The Mets hadn’t made the playoffs in seven seasons, their lone World Series victory came in 1969, and Strawberry was branded the guy who could lead them to another championship before he even got to New York. His first year in the minors, the Kingsport Mets let fans in for free on Sundays if they brought a strawberry to the park. When he was called up to the big club in May of 1983, during what looked to be another dismal season, Strawberry mania hit a boil. “He was the story,” says the team’s 35-year public relations man, Jay Horwitz, whose memory is a Mets library. “He was expected to hit a home run every time up. If the guy’s name is Darryl Smith, it probably wouldn’t have been as bad. But Darryl Strawberry? A six-foot-six kid with a ton of talent? That put a lot of pressure on him.” And Strawberry played to it. He crushed 26 home runs and ran away with the NL Rookie of the Year award. Nobody got out of their seat for a hot dog when Strawberry was at the plate, because no fan wanted to risk missing a 500-foot dinger. In 1985, he cracked a homer off Reds left-hander Ken Dayley that hit the clock on the right-field scoreboard at Busch Stadium. On opening day in 1988, he authored a moonshot that looked like it would carry for days but hit the cement rim of Olympic Stadium’s roof in Montreal. Says Hall of Fame Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda: “He had as much power as anybody that’s ever played.” And about as much pomp, too. The man was an entertainer, taking what seemed like 10-minute long trots around the bases after a homer. “I always thought, take your time and enjoy it; what’s the hurry?” Strawberry says, grinning. He revelled in the taunting “Da-rryl! Da-rryl!” chants he’d get at away parks while he stood in right field, tipping his hat to the other team’s fans. Today, if you ask him to, he’ll imitate the chants.

1983: Hits 26 homers, steals 19 bases, wins NL Rookie of the Year. Credit: BRUCE BENNETT/GETTY IMAGES

What endeared Strawberry to the legions of fans who sought his autograph decades ago hasn’t changed; he’s amiable and approachable, an open book. He immediately nicknames the waitress during a lengthy menu consultation before he goes with meatballs and a side of pasta with sausage. “All right, I’ll trust you, Lise,” he says, handing over the menu. Sipping on a diet Pepsi, Strawberry says he loves New York. But his eyes widen and he shakes his head when asked if he was prepared to play there: “No.”

It was a hell of a time to be a Met, on and off the field. From 1984–1990, the team never finished worse than second in the NL East, with a roster that included No. 1 draft pick Dwight Gooden (another potential-filled youngster who’d fall hard) and veteran stars like Gary Carter and Keith Hernandez. It was a different time in baseball—players drank, smoked, did coke and speed and popped amphetamines in and outside the clubhouse. That fast, hard living permeated every part of the Mets’ identity. They were the brashest team in baseball, involved in five bench-clearing brawls in a single season. “We didn’t take no nonsense. We in-house fight, we out-house fight,” Strawberry says. “It was a bad bunch o’ boys, there.” Strawberry tried cocaine for the first time the week he got called up to the majors, thanks to a teammate who set up his first line in a bathroom stall at the clubhouse. “Once I got into coke, that was it,” he says. “Loved it.” And much more than most. He’d party until 5 a.m. with the pitchers who didn’t have to play the next day. When teammates criticized Strawberry for his off-field behaviour, for showing up drunk or for missing a workout because he was hungover, he ripped them back: On team photo day, he took a swing at Hernandez (then kissed the top of his head and made up 24 hours later). Strawberry said he was sick and missed two games in July of 1987, but used the time off to record a rap song (“Chocolate Strawberry”; it wasn’t a hit). When second baseman Wally Backman called him out, this was Strawberry’s response: “I’ll bust him in the face, that little redneck.” Teammates called Strawberry a walking stick of dynamite. They’d pass by him and say, “Tick, tick, tick.” He regrets none of it. “That’s part of it, there’s egos and stuff that gets involved. That’s the nature of the beast in us,” Strawberry says, shrugging. “Here’s a guy, multi-talented, could do whatever I wanted on the ball field. I was confident, not cocky. It’s a big difference. There was no doubt in me. I wasn’t afraid to fail.”

And fail he did. Oh so famously. Three times MLB suspended Strawberry for cocaine use. Every team he played for—the Mets, the Dodgers, the Giants and the Yankees—tried to control his behaviour. And for every club after the Mets, Strawberry said he’d start fresh, claimed he was reading the Bible daily, or had become a staunch member of Alcoholics Anonymous, or was ready to start a new life, or had cleaned up after his latest stint in rehab (he thinks there were four or five), or all of the above. His first reinvention came in Los Angeles, where Strawberry signed a five-year, $20.25-million deal ahead of the 1991 season. The previous off-season he’d been arrested for drunkenly pulling a gun on his then-wife, Lisa, and breaking her nose. Strawberry had since made his first visit to rehab for alcohol abuse and declared himself a born-again Christian. Lasorda’s wife took Strawberry with her to church. The team even employed the only full-time psychiatrist in baseball. “He promised me he wouldn’t give in,” Lasorda says. “I believed him, yeah. I did. He had it all right there, in the palm of his hand.”

It was in L.A. that Strawberry earned his eighth and final all-star team selection. It was also in L.A. that Strawberry tried crack for the first time. Newly divorced from Lisa, he got drunk and hit his pregnant girlfriend and future wife No. 2, Charisse. Lasorda has one word for how he felt when Strawberry fell short on his promise: “Irate.”

The Giants went a step further to protect Strawberry from himself when they signed him ahead of the 1994 season: They put his oldest brother, Mike, on the payroll. Then an LAPD officer who worked narcotics, Mike handed in his gun and badge—giving up the job he’d been dreaming about since Grade 8—so he could chaperone his 32-year-old millionaire little brother. Mike travelled with the team, had the locker next to Strawberry’s, worked out with him, and was on his case about keeping clean. “It would appear, talking with him, ‘Oh, he’s getting this.’ Several times. I believed him. That was part of my demise,” Mike says. That off-season, Strawberry tested positive for cocaine. The Giants dropped him. “I gave up my livelihood to support you and help you,” Mike told Darryl. “How could you do this? You have everything you could possibly want, and you messed it up. Again.”

Strawberry had more than everything he could possibly want. “You think you’re King Kong or something,” he says, throwing his hands up. “I look back on a lot of that stuff and think, what a waste.” Strawberry describes flinging $100 bills out of the window of his limo after he made $15,000 in cash at card shows. He once bought a black 560 SEC Mercedes and had the top cut off to make it into a convertible because he didn’t like the convertible style on offer. In the late ’90s, he lived in a $2-million home with a marble foyer and tennis courts and pools in a gated community in Palm Springs, Fla. He’d buy 50 pairs of shoes at a time. “Gimme one of those, those, those, those,” he says, pointing in the air at his fictitious selections. His approach to women, whether he was married or not, was similar: “You want one short, you want one tall, you want one blond, you want one brunette. Whatever suits you.” He believes 90 percent of men are “addicted to women.” The divorces from his first two wives, Lisa and Charisse, were like a bath left running for centuries: Strawberry figures they cost him $7 million. “People think, well, you made $40 million, it’s gonna last forever. It doesn’t,” he says. The only thing that didn’t cost him was drugs: “I got ’em free.”

Darryl Strawberry The Baseball Player disappeared for good in 2000. In 1999, he’d won a fourth and final World Series title with the New York Yankees as a 37-year-old DH. He hit .327 in 49 at-bats during that championship season, and he’d cleaned himself up after starting the season under a drug suspension. It could’ve been, should’ve been a nice end to a tumultuous career, a final solid year in New York, where he started. But in January of 2000, Strawberry tested positive for cocaine and MLB suspended him for a full season. And that was it. He’d swung a baseball bat for the last time ever. He hit 335 home runs, still holds the Mets record in that category, and had 1,000 RBI. “I reached all that drinkin’ and druggin’,” he says, matter-of-factly. And once he was done with baseball, that was all he had left.

wo Armani suits come flying out the back of the truck. Baseball jerseys, T-shirts, shoes and pictures follow, all chucked on the front lawn. An irate blond woman, propeller of the belongings, is now pounding on the front door, screaming for Darryl Strawberry to get the hell out. Her car, which he stole to drive here, is parked on the street. He hears her call his name but he’s not answering. “That’s it!” she yells. “You can get yourself out of this mess!”

wo Armani suits come flying out the back of the truck. Baseball jerseys, T-shirts, shoes and pictures follow, all chucked on the front lawn. An irate blond woman, propeller of the belongings, is now pounding on the front door, screaming for Darryl Strawberry to get the hell out. Her car, which he stole to drive here, is parked on the street. He hears her call his name but he’s not answering. “That’s it!” she yells. “You can get yourself out of this mess!”

Inside this Boca Raton, Fla., crack house, Strawberry is out of his mind. He won’t come outside because he’s getting high with three women. He doesn’t care that his belongings are strewn all over the lawn because he’s too busy smoking dope. A couple of hours later, he collects his stuff. A few hours after that, when he notices his girlfriend, Tracy Boulware, has reclaimed her car, he calls her, crying. “Come get me,” he says. She won’t.

Asked if this was rock bottom—and you’d be hard-pressed to find a man with more options to fit that label than Darryl Strawberry—he shakes his head. (After all, Tracy Boulware is now Tracy Strawberry. She did give him another chance.) No, rock bottom came a year earlier, in April 2002. At 40 years old, Strawberry stood before a judge in a Hillsborough County courtroom, given a choice between six years of probation and an 18-month prison sentence. His decision: “Lock me up. I’m dead anyway.” He’d spend 11 months behind bars, a shorter sentence thanks to time served. The road there was a long one, and this is why it takes the all-time low title in Strawberry’s books: More than two years earlier, he was arrested in Tampa for cocaine possession and soliciting prostitution (the incident that led to his year-long suspension from MLB). Six times since, he’d violated the probation stemming from those charges. He was kicked out of one drug treatment facility after having sex with a woman in the program. He broke out of another recovery facility, despite the ankle bracelet designed to keep him there, to hole up in a crack house. Four days after that, he turned himself in to friends. They drove him directly to a nearby hospital’s psychiatric ward, because he told them he wanted to die. “I had nothing left to give my kids,” he says of that time. “No love for them, no love for myself.”

You have to wonder, all this considered, why Darryl Strawberry doesn’t look godawful today. He’s even fought cancer—twice; first in his colon and then in his lymph nodes, though he’s clear today. But there’s no sign on his face of the crap he’s been through, no sunken cheeks, nothing defeated in his expression when he talks about those lows. The man looks good, and he says it’s because he’s born again, happy for the first time in his life. He says the start of his turnaround—though he’d visit more than a few crack houses after this—began shortly after his rock bottom, during that 11-month stay at a Gainesville prison, where he did yardwork on the grounds and was by all accounts a model inmate. Gainesville had a baseball field and Strawberry coached one of the softball teams. Many of his fellow inmates, obviously, begged him to suit up, but he never even picked up a bat or a glove. “I was done with baseball. After all, I mean, I’m sitting here in the Florida State prison. What am I gonna be doin’, playin’ softball? Livin’ the dream? Trying to bring memories back or something?” Strawberry’s chuckling. “I don’t think so!”

There’s no pretentiousness to Strawberry today. He swears he’s “nothin’ special.” Back when he was taking drugs, he’d walk into a crack house and say: “You and me, we’re the same, we’re both sittin’ here, we’re both usin’.” The first time Tracy laid eyes on him was at a narcotics convention in Florida in 2003. Strawberry was chatting, smiling and engaging a crowd that had formed around him. Tracy wasn’t impressed. “Everyone’s going crazy because they don’t see this fragile man that is dying, that has lost his soul,” she says. “All they see is the baseball player, the home runs he hit, the celebrity.”

Strawberry noticed the pretty blond woman, heard her say she wanted to leave. He shook her hand with both of his and convinced her to stay. “She was different,” he says, between bites of meatball. “She didn’t care that I was a baseball player.” The two spoke for hours, but never about the game. To this day, seven years after they married at a tiny Las Vegas church, both wearing jeans and tennis shoes, Tracy doesn’t know his stats or the details of his career. She doesn’t care. The afternoon they met, Strawberry told her: “Girl, you have no idea what you’re getting into. You don’t wanna mess with me.” Tracy was drawn in by his honesty.

Then only recently clean herself after a 12-year battle with alcohol, coke, crack, crystal meth and whatever else she could get her hands on, Tracy rescued him over and over, beat down crack-house doors and dragged him out. “It’s a classic love story!” Tracy says, laughing. She’s a sparkplug. When Strawberry faltered, she told him, “I’m gonna love you out of this.” But there were times when her faith flagged. About a year after they first met, she moved back to her childhood home, in St. Charles, Mo., to live with her parents. She told Strawberry she didn’t care if he came or not, she needed to move to continue her recovery. “I told him,” she says—and this is where that Missouri drawl gets extra heavy—”I’m suitin’ up and showin’ up and growin’ up, and you gotta do the same.”

Strawberry says he balked at first (“There ain’t no black people in Missouri!”) but eventually followed Tracy there (“I ain’t got nowhere else to go”). Together, they lived in her high-school bedroom, slept in the same bed she slept in back then, stared at the same 1970s linoleum floors. He cried, a lot. A four-time World Series champion living in his girlfriend’s parents’ basement, unemployed and $3 million in debt thanks to unpaid child support and back taxes. He’d lost everything and then some. Strawberry didn’t even have a driver’s licence. “Is this all life has left?” he asked himself. “Where do we go from here?”

By the time they moved to Missouri, both Tracy and Strawberry had embraced religion, he for about the 10th time. Strawberry had lived there less than a year when Tracy told him they couldn’t have sex anymore because they had to “do right by God.” He smiles: “Defining moment in my life.” He left and moved in with his sister Regina in San Dimas, Calif., about 25 miles west of L.A. For six months he helped her take care of her three kids and he read the Bible and he lived clean. At 42 years old, this was the end of Darryl Strawberry The Addict. The toughest of his vices to give up: “Drugs,” he says. Then he quickly amends his answer. “Drugs and women. They run hand-in-hand.”

Strawberry finishes off his meal. He uses his index finger to pick a chunk of meatball out of his braces. “I was ready,” he says. “I was finally ready.”

arryl Strawberry wants to know how many of the 30 or so kids in this room with JESUS written on the wall in metallic letters have low self-esteem. “Hands up,” he says. He’s at Cornerstone Youth Center, off High Street and just past Peace Alley, here in this town full of churches and American flags, addressing a room full of people who weren’t alive the last time he swung a bat. A bunch of hands fire up. “I’m gonna build you self esteem, and I’m gonna build you something to walk out of here so you can be proud of who you are,” Strawberry says. His hands are in the pockets of his dark blue jeans, and a silver bracelet that says “Believe” in dark letters hangs off his right wrist. “God created you,” Strawberry says, eyes wide. “You’re not a mistake.” He pauses. “You’re not a mistake. Don’t ever let anyone tell you that you are.”

arryl Strawberry wants to know how many of the 30 or so kids in this room with JESUS written on the wall in metallic letters have low self-esteem. “Hands up,” he says. He’s at Cornerstone Youth Center, off High Street and just past Peace Alley, here in this town full of churches and American flags, addressing a room full of people who weren’t alive the last time he swung a bat. A bunch of hands fire up. “I’m gonna build you self esteem, and I’m gonna build you something to walk out of here so you can be proud of who you are,” Strawberry says. His hands are in the pockets of his dark blue jeans, and a silver bracelet that says “Believe” in dark letters hangs off his right wrist. “God created you,” Strawberry says, eyes wide. “You’re not a mistake.” He pauses. “You’re not a mistake. Don’t ever let anyone tell you that you are.”

This is the narrative that ran through his own life. Strawberry claims his pop, Henry, was an “alcoholic who beat the crap out of me as a kid, told me I’d never amount to nothin’.” Henry threatened the family with a shotgun and left when Strawberry was 13. “Why did my father not love me? I struggled for a very long time with low self-esteem and identity,” he says. “I had millions of dollars, all the kind of stuff you could want, but I had nothing inside.” It’s this “inside work” he tells the kids here to focus on. “If I could do it all over again, I woulda never played baseball,” Strawberry says. “If I knew I woulda had to go through all that hell just to play baseball, I woulda chose God.” The last message, before he leaves for the evening event to benefit Cornerstone, is that everyone should get to know Jesus, “because he’s so cool.”

This is Darryl Strawberry’s third life, as “a leader for God.” A minister who travels around the U.S. giving sermons and religious speeches, he’ll do some 50 appearances in 2014, including a conference in front of 10,000 men in June in Tampa, Fla. Pastor Strawberry hasn’t gotten high or had a sip of alcohol or said a curse word in 11 years. He calls sleepy St. Peters, Mo., home, and his idea of a night out is a slow walk while he holds hands with Tracy, herself a minister. They live in a four-bedroom, two-storey home worth $500,000—five months worth of alimony and child support, back when he was a ball player—and when they barbecue hamburgers outside in the backyard they can see their neighbours on either side. Strawberry drives a GMC Yukon and Tracy drives a Nissan, and there is absolutely no sign in their home that the guy residing here ever swung a bat.

But it’s baseball that pays Strawberry’s bills. That’s how he got out of debt, collecting $500 and $1,000 each time he made an appearance—low fees thanks to a tarnished reputation—and putting the money toward that $3-million hole he’d dug himself into. “I owed everybody,” Strawberry says. He and Tracy called debtors and explained their situation, got payments reduced. They found out Strawberry owed another $1.2 million, thanks to interest and other back taxes. It took five years to get out of the red. Strawberry’s now comfortably in the black; he earned some $300,000 last year in baseball-related appearances. It helps put his kids through college. (He has six, with three different women. His youngest, Jewel, 13, lives with her mother, Charisse, and has her eye on the University of Florida and a volleyball scholarship.) As for the money he makes for his religious work, Pastor Strawberry says he told God he’d use it to help others. He isn’t naive about the fact that baseball’s the reason people want to hear him speak. “They want to know, how does your life transform like that. How’d you get through hell and get here,” he says. The past lives—The Baseball Player and The Addict—are fuelling this new identity, and Strawberry says it’s all part of God’s master plan. “It’s bringing a message that can make a difference in somebody’s life,” he says. The $6,000 he collects for today’s appearance in Elizabethtown goes back to Strawberry Ministries, the O’Fallon, Mo.-based Christian organization he and Tracy founded last year. A couple months ago they opened two recovery centres for addicts.

Strawberry credits Tracy for turning his life around. Her name is inscribed with his on the outside of the thick, black wedding ring he wears. As he’s talking about their work, he cuts himself off mid-sentence and races up to his hotel room to grab the book they’ve co-authored, The Imperfect Marriage: Help for those who think it’s over. It’s full of tips from the Strawberry ministers, who between them have four failed marriages and one success story. The book hits shelves in August. Imagine that: Darryl Strawberry, Marriage Expert.

Even more unbelievable is Pastor Strawberry’s stance on baseball. This man named his first kid Darryl and his first daughter Diamond, and not after the gem (Jewel and Jade, his other daughters, are another story). Yet he has no pictures, no bat, no glove, no ball, nothing left from a career in the game (though he says the location of his four World Series rings is “private”). Strawberry says he hasn’t swung a bat since his last Major League rip in 1999. He won’t hit a ball if you offer to pay him. Throw a foam one in his direction and he’ll let it bounce off his chest. He hasn’t worked out since the Yankees, and there’s a small paunch above his waistband to prove it. “Baseball is a past memory. I’m done with that,” he says. “It’s not my purpose.” Rarely does he watch MLB games on TV; Pastor Darryl, as Tracy calls him, would rather hole up with the Bible. “Once I took off the uniform, I took it off,” he says. “Some players, the uniform becomes your identity, who you are. I needed to find out who I really was.”

Back in Elizabethtown, Pastor Strawberry looks up at the Mount Calvary gym ceiling, smiling. “God spared an old thing like me,” he says. The hands-free mic that extends from his right ear toward his mouth is pale, and would blend in with the skin of any other person in this room, but not his. He’s the only black person here.

“Look what He’s done!” Strawberry says, arms waving. His 47 minutes at the mic are just about up. He’ll spend the next 40 absorbing applause, shaking hands, smiling for pictures and listening to stories guys want to tell him about seeing his 300th homer live, or about the Strawberry poster they had on their bedroom wall as a kid. Nobody talks to him about Jesus—this crowd is a mixture of churchgoers and baseball diehards, but it’s heavy on the latter. One guy wears an old-school shiny Mets jacket. Earlier, a woman paid $1,075 for a signed Mets Strawberry Jersey, the highest earner of the auction (the quilt on offer didn’t do as well).

Strawberry will talk to everyone, call them “sweetie” and “buddy” and thank them for coming. After a photo shoot with one of three Bibles found in the high school’s office—”This is my favourite book, right here”—Strawberry will be done. Tomorrow morning, he’ll fly to Tampa for another appearance, to preach and to tell his story. He ends today’s talk with a prayer, but first he reminds his audience why they’re here in this high school gym on a Thursday night eating grocery store–bought apple pie with plastic forks. “All those that wrote about me, said that I would be dead in a couple years,” Strawberry says, grinning. “Guess what? They was wrong.”

Almost Done!

Please confirm the information below before signing up.

{* #socialRegistrationForm_radio_2 *} {* socialRegistration_firstName *} {* socialRegistration_lastName *} {* socialRegistration_emailAddress *} {* socialRegistration_displayName *} By checking this box, I agree to the terms of service and privacy policy of Rogers Media.