In Indiana they called it the “motherf—-r clock.” And it explains everything you need to know about Tyler Hansbrough on the basketball court. “As a coaching staff we’d always set up a timer in practice. And it was to measure how long it would take for Tyler’s matchup to call him a motherf—-r,” says Frank Vogel, Hansbrough’s first NBA coach. “It seemed every five minutes you’d see the guy he was guarding throw his hands up and go, ‘This motherf—-r right here, I swear I’m gonna…’ Every practice. Every game. It became like our own office pool. Like, ‘How long do you think it’ll take today?’”

In his six NBA seasons, Hansbrough has earned a reputation as one of the league’s premier agitators, a brutish menace whose relentlessness brings out the worst in others. You may know him from such YouTube videos as: “Tyler Hansbrough tackles Mike Dunleavy,” “Sebastian Telfair slaps Tyler Hansbrough in the face,” “Will Bynum gets ejected for punching Tyler Hansbrough,” “Tyler Hansbrough stands up for brother Ben,” and, simply, “Bloody Hansbrough.”

You may also know Hansbrough as the former face of college basketball, the 2008 National Player of the Year and Sports Illustrated cover boy (twice) who led the North Carolina Tar Heels to a championship in 2009. Or, more recently, as the Toronto Raptors’ de facto enforcer, a player GM Masai Ujiri brought in to add an element of toughness that had been missing since Charles Oakley rocked the purple and black.

But chances are you don’t know Hansbrough as the quiet, shy middle child from a small-town Missouri family, as an inspired spokesperson and advocate, or as the self-proclaimed “most laid-back guy in the whole locker room.”

His brash playing style and the success that it’s bred have made Hansbrough a polarizing figure, a walking archetype of the player you love when he’s on your team and hate when he’s not. But take the guy off a basketball court and you’ll be hard-pressed to find a more, well, normal pro athlete. Turns out Tyler Hansbrough isn’t who you might have thought.

Photo: Christopher Wahl

On a cold November morning after practice, Hansbrough ducks his head under a door frame, sweat still dripping off his brow, and barges onto the empty Air Canada Centre concourse.

His handshake is firm, unsurprising from a guy who maintains with a straight face that he can do 150 push-ups in a row. When there’s not a camera in his face, he’s very animated as he talks, shifting from one foot to the other, engaged and interested. His voice, disarming and in a higher register than you’d expect from someone listed at six-foot-nine, can throw you off at first, and he often punctuates his sentences with: “To be honest with you.”

When asked about his effect on opponents, he flashes a grin. He’s been asked this before. “It’s not something I’m really cognizant of,” Hansbrough says. “Sometimes I just play so hard that some people mistake that for playing dirty or whatever you want to call it. But it’s not. Most people don’t play that hard, and I think it’s why I find myself in these altercations, bugging people.”

A few days earlier, the Chicago Bulls were in town to play the Raptors. In the Bulls locker room before morning shootaround, Joakim Noah sat in one corner, flanked by Kirk Hinrich and Mike Dunleavy Jr. When asked about Hansbrough, Noah and Hinrich shot each other a knowing glance, and through pursed lips tried to hold back smiles. “He’s a full-contact player,” Noah offered.

Dunleavy, a former teammate of Hansbrough’s with the Indiana Pacers, elaborated a bit. “There are two sides to Tyler,” he said. “Off the court he’s a really nice, relaxed guy. I don’t think a lot of people realize that about him, because he’s such an intense, hard-playing dude.”

While coaches and teammates love him for it, that intensity has taken a toll. In 2011, Hansbrough took an elbow to the side of the head from the Knicks’ Kurt Thomas and dropped instantly, lying motionless on the floor for over a minute. When the medical staff walked him to the locker room, he barely got past the tunnel before losing his balance. They got him off his feet and began testing. It was revealed he had suffered a concussion, his third in four years. This one was the worst. “It was a real test,” says Dr. Gene Hansbrough, an orthopedic surgeon and Tyler’s father. “There was a real change in his personality. He was more withdrawn than ever.”

The concussion took Hansbrough away from basketball for nine months. He went to rehab at the University of Pittsburgh and moved in with his dad during the recovery period, rarely leaving the house. A short walk around the corner would leave him dizzy, and the highlight of his day was playing with his dad’s bulldog in the backyard.

Hansbrough has always been close to his family. Sandwiched between two brothers—Greg, two years older, and Ben, two years younger—he was the shyest of the trio. His father recalls fondly how Greg relished the role of big brother. When they’d visit the neighbour’s house—Tyler following like a puppy—Greg would ask for candy while his brother stood silently. “And Tyler wants some, too,” he’d say on his behalf.

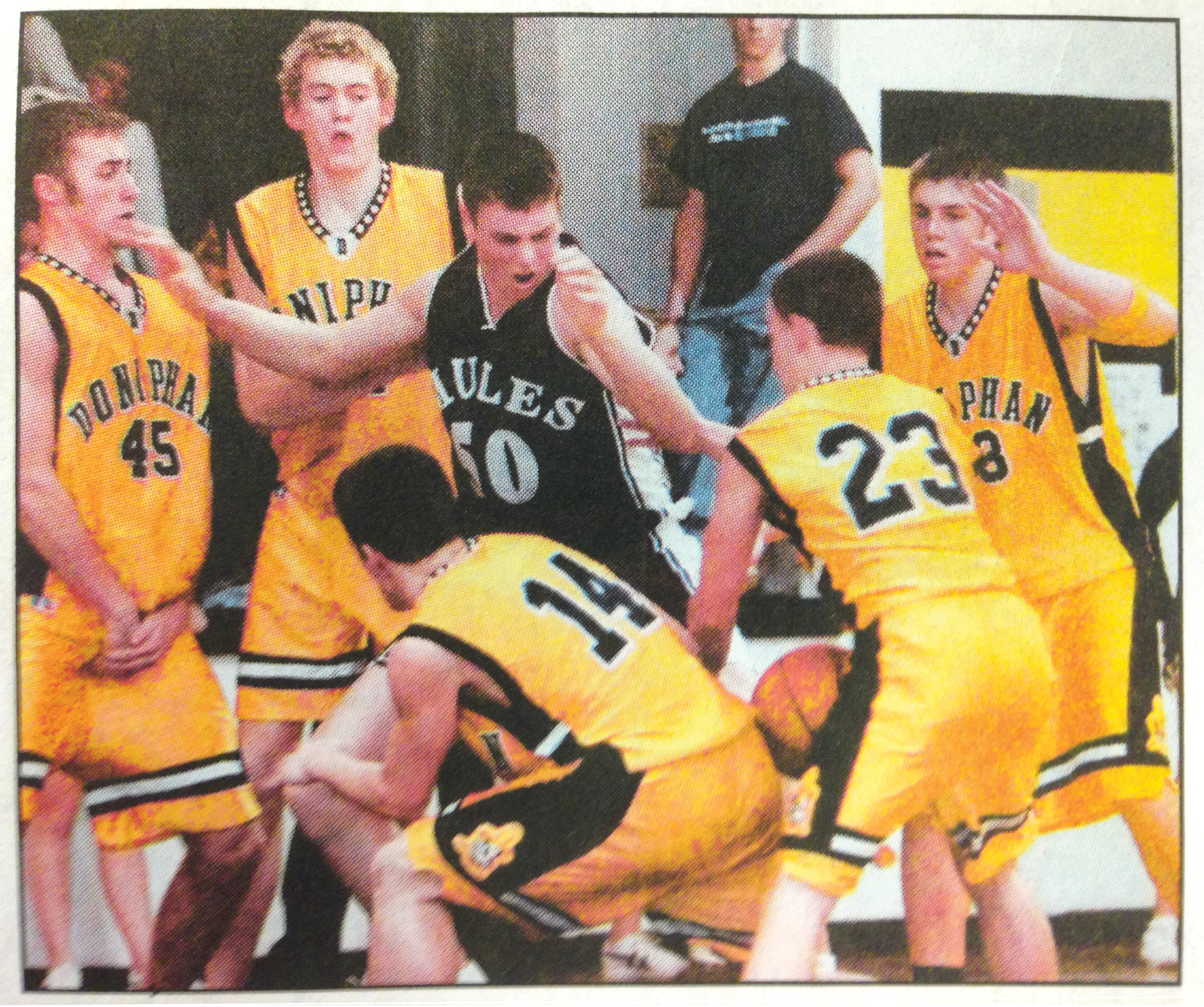

But when it came to sports, Hansbrough was in his element. When he was in Grade 1, Hansbrough was a reserve point guard for the Grade 6 team and was starting by Grade 4. Even then, he’d get to the gym early so he could make 100 free throws before each game, and carried that work ethic to the next level. “I’ve never been around a kid more focused, whether it’s in the gym, lifting weights, his diet,” says Hansbrough’s high school coach John David Pattillo, who first saw him play when he was nine years old. It wasn’t long before Hansbrough was a local star as the varsity basketball team at Poplar Bluff High became the hottest ticket in town en route to two state championships. As his father puts it: “When we were at the state tournament you could rob a bank and nobody would know.”

Yet, as his reputation grew, Hansbrough became a bigger target for opponents. “Everybody was fouling him constantly, knocking him around,” recalls Pattillo. “One game I had to take him out in the first half because the kids were undercutting him and it was dangerous. It’s sad that they had to resort to that; it was the only way they thought they could compete with him.”

With Tyler starting at forward and Ben playing guard, the brothers formed a dynamic duo, each fuelling the other. “Those two always competed like demons—whether it was eating the last cookie or making free throws,” Gene says, his Missouri drawl considerably stronger than his son’s. Ben, who played alongside Tyler for one season in Indiana (Vogel recalls the two getting into fist fights in practice), helped his brother become a better player, but their father says that “the real story behind their motivation lies with Greg.”

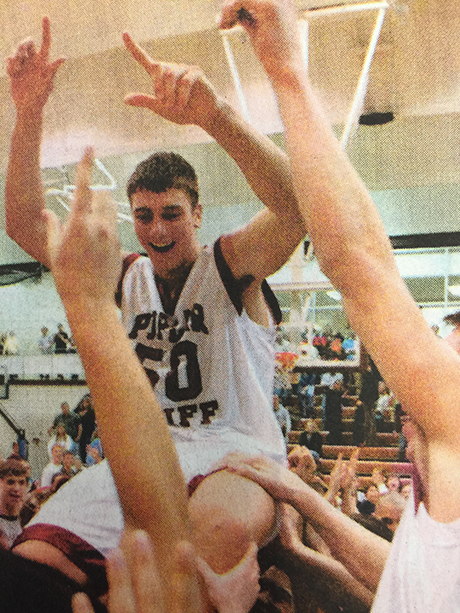

When Greg was seven years old, the doctors found a tumour in his brain. Even at a young age, Greg was already a dominant athlete, a track star in the making who could jump like a deer. But when doctors successfully removed the tumour, they said it was likely that he wouldn’t walk again. “I saw him go through the whole thing,” Hansbrough says. He watched his big brother regain his motor skills and relearn how to read and walk. Within a few years, Greg was not only walking, but running. He even played four years of high school basketball—the last two alongside Hansbrough. Gene admits his frustration in trying to find purpose in his son being dealt such a hand, but came to see how Greg would impact others. “He’d score a basket and people would go crazy.” Today, Greg is an avid marathon runner, and still the biggest inspiration in his brother’s life. “That’s the reason I wear number 50,” Hansbrough says, proudly lifting his jersey forward. “That was his number, and I said I’ll carry on the tradition for him.”

Recently, Hansbrough became the first athlete spokesperson for Voices Against Brain Cancer, as he tries to raise awareness for the cause. He’s also a public advocate for concussion testing, digging into his own experiences to share his message with others. “Sometimes people want to limit you,” Hansbrough says. “They wrote Greg off. Greg never listened to those doctors, and he kept getting better and better. I saw there were no limits to what you can do based on other people’s thoughts. I learned that from my brother.”

It’s a lesson he’s been able to translate to basketball, too. Nobody thought Poplar Bluff High could be a springboard to a program like North Carolina. At UNC, people said Hansbrough’s game couldn’t translate to the NBA, that his size and strength advantage would be negated. Even this summer, when he added the three-point shot to his arsenal, many in the media said he should stick to the low post. Yet at practice in November, Hansbrough beat Terrence Ross in a three-point shootout as those same people looked on, suddenly silent.

Photo: Christopher Wahl

“The biggest misconception about Tyler is that he’s a mean guy, a brawler,” says Gene. “He has toughness, that’s all. I always told him: In life you can’t back down. Once you do, you’re a target forever.”

“Sometimes,” Hansbrough says, “fans run into me and they expect me to be crazy or do something off the wall. But I’m not a big talker and have always been a quiet guy. It catches people off guard. It’s not like I morph into someone else when I step on the court. It’s just the way I play. I play hard.”

This story appears in the Dec. 8 issue of Sporstnet magazine