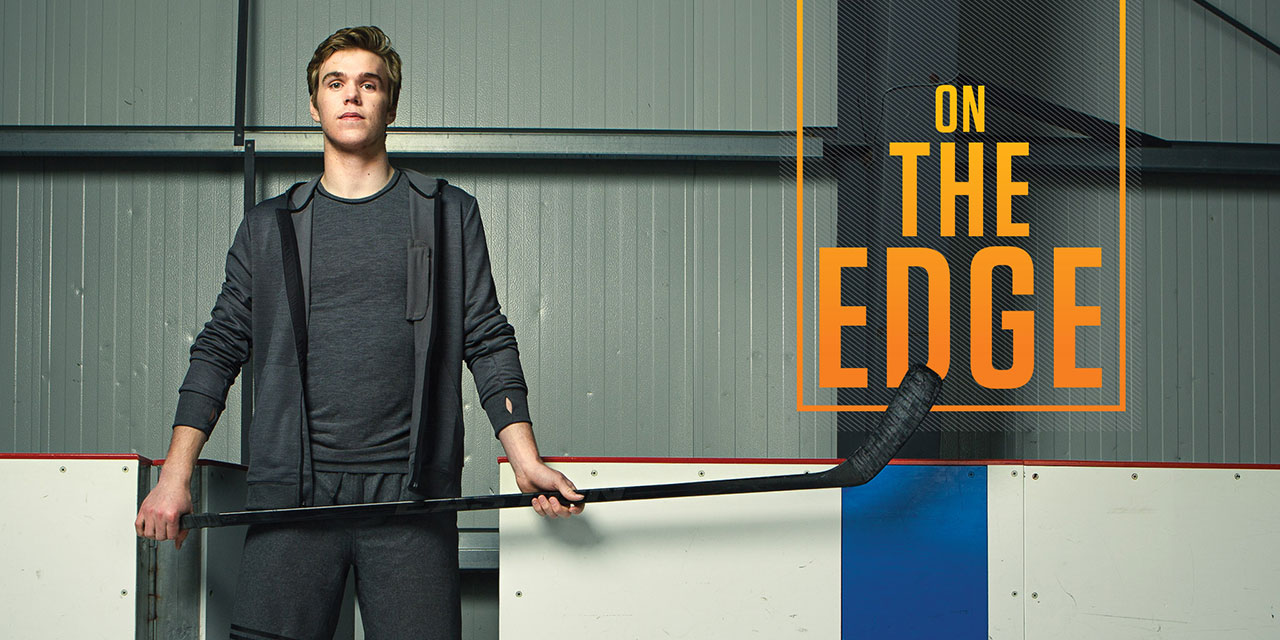

Soon, he’ll be Connor McDavid—Oilers saviour, transcendent superstar, face of the NHL. Right now, though, he’s just an 18-year-old kid who’s quickly running out of normal days.

By Gare Joyce in Erie, Newmarket, Oshawa and Quebec City

Photography By KC Armstrong

It’s after eight a.m. and Connor McDavid is rolling out of bed late. He comes downstairs and stumbles into the kitchen. He asks his mother how his father is feeling. “Still sick,” Kelly says. She also tells her younger son that he’ll be late for school unless he picks up the pace. It’s only around the corner and down the street, but still. She knows he was up late, too late, watching the Anaheim-Chicago game stretch into overtime. After the first OT his iPhone pinged: Bobby Orr with a reminder that a kid like him needs his rest. But there was no way he was going to be able to sleep without knowing who won.

Kelly might sigh but won’t get on Connor too hard. She’s just glad to have him home, even if she tells visitors that “the place is upside down” with him back and it’s only been a week. She tells them that he hasn’t unpacked his stuff from Erie, that she has no idea when or even if he’ll get around to it. After all, a lot of it stayed packed up all season, still folded and boxed up from last August. When he’s out of earshot, she talks about her kid becoming “a real clothes horse.” She could never have seen that happening. The picture of him in her mind is still the kid in the splash pants, sweatshirt, running shoes and baseball hat, stickhandling in the driveway. Forever 10.

Kelly and her husband, Brian, will be certified empty nesters soon. They’ve had three years to get ready, mind you, with their older son, Cameron, enrolled in the Ivey Business School at Western University and Connor moving through his rite of passage in the hockey business in Erie, Pa. This summer it’s just going to be Connor who’s home, because Cameron landed an internship with the Swiss bank UBS. “A dream job,” she tells her friends proudly. It’s in Toronto’s financial district and he’d be an hour or more in traffic every day if he stayed out in Newmarket, so Cameron is renting an apartment downtown. Connor has his run of the house, then, for the first time since Cameron headed off to London. Back then, Connor was 14, not yet a household name, the phenom for the ages and all of that. It happens so fast. It happens too fast.

Kelly knows that Connor will make it to school. He always manages to get it all done. Always has, God knows how. When she sees Connor head out the door, she smiles. She knows it’s not just the clock ticking on the first bell of the school day but the last bell of his school days. “He’s in a good place,” she says even though he didn’t make his bed.

Connor McDavid needed time in this good place after the longest hockey season of his life. He needed to drop out of sight, to decompress. His circle of family, friends, agents, management and teammates knew there was no way to go into lockdown mode, insulating Connor from the world—better to let people in but make it a controlled situation, taking a few requests, politely declining others. That said, at times it had to seem like the dam was about to burst, the slow drips turning into a flood.

It began with a documentary crew tracking him at the start of the season and parachuting in at scheduled junctures. Then in November fans wanted to know what he was thinking when he threw a wild punch at Mississauga’s Bryson Cianfrone and broke his hand. Then about five seconds after that they all wanted to know if he would be healed in time for the World Junior Championship, and were assured that he was going to be there. Probably. And when it came down to it, he was there, a centre of attention at the biggest world juniors in the 40-year history of the tournament, playing out of Montreal and Toronto. Next, fans asked, “Shouldn’t he be on the first line?” and “Why hasn’t he scored?” But by tournament’s end, his talent had shimmered even more brightly than the gold around his neck and almost as brightly as the camera lights that shrunk his pupils to the size of pinholes. And when he left the ACC after the final, his father drove him home to Newmarket to sleep in his own bed, which was the nearest thing to a vacation McDavid had this winter. The next morning he left for Erie, couldn’t get away from the hub of hockey media fast enough. Avoidance but not escape. Yeah, across the rest of the season, there was enough media attention to give a practised public figure vertigo, claustrophobia and hives. Doubt it? Google “McDavid” and “tank.” Or go to eBay and price limited-edition autographed memorabilia or bid on a No. 97 Buffalo Sabres sweater. And it all led up to an hour of television on April 18; Connor sitting in a studio beside his Erie teammate Dylan Strome and Boston University defenceman Noah Hanifin and under the unblinking gaze of the cameras and those of brazenly covetous NHL executives. He looked like he just wanted it over with. In those awful minutes his future hung in the balance alongside that of more than one franchise. All his work having brought him to a simple matter of chance and…

But enough of that for now. Because McDavid’s moved from that tumult and ubiquity to this good place. And it must have seemed like he’d never find it again.

No. 99? 87? Try 42 While coaches, GMs and awards tend to group McDavid with the likes of Gretzky and Crosby, his own point of comparison is a bit more humble: Tyler Bozak

It’s the Friday night leading into the Victoria Day weekend. Connor McDavid lets his father, Brian, loose from a sweaty hug, turns and pushes through the door to the visitors’ dressing room at the General Motors Centre in Oshawa. He can hear the cheers for the home team, just so much white noise. No telling what music they’re playing out there, just the thump of the bass like a heartbeat.

Minutes after the end of their season, the realization kicks in: The Otters were this close. They coulda, shoulda won game two, dominating the Generals in Oshawa, but they ran into a hot goaltender, who stole three slam-dunk chances off McDavid’s stick. They were on the verge of tying the series in game four, but a delay-of-game penalty in overtime gave way to crushing disappointment. McDavid watched from the bench when Cole Cassels scored on the power play to give the Generals the win and a three-games-to-one lead in the Ontario Hockey League championship series. And then there was tonight, when the home team proved too talented, too deep and too prepared for whatever McDavid might throw at them. If, if and if, he’s thinking, and then the door closes behind the coach and the room falls silent. “I’m proud of you,” coach Kris Knoblauch begins. “We were picked in the bottom half of the conference before the season and …”

Knoblauch does a quick emotional inventory of the room. He sees the bowed heads and bobbing shoulders, not just the younger players but the over-agers too. Maybe the over-agers most of all. It’s just kicking in, the likelihood that this was the last meaningful game they’ll play. Knoblauch knows it’s pointless to go on. He and his assistants leave the room, go out to the bus and take their spots in the front seats.

One by one the players board in silence. McDavid takes his seat toward the back. A head count is done and the bus rolls out of the parking lot. After a win there would be whooping and laughing, after any other loss dead silence, and with any outcome 20 kids fast asleep before they hit the 401. But not this night. No, the coaches can hear stirring in the back—the low murmur of McDavid talking to his teammates, barely audible above the drone of the bus.

McDavid’s season and his junior career are over but there’s still a “C” on the damp sweater that’s down in the hold of the bus. There are natural-born leaders even at this age: charismatic, effortlessly magnetic, unerringly intuitive. McDavid has never been such an Alpha Boy. He came to Erie shy, almost hopelessly so, and, in open defiance of all his talent, nervous. It seemed he took his craft so seriously that he feared engaging with the world would compromise it; that he was so concerned about violating veterans’ space he tried to fade into the background. Older teammates beseeched him to loosen up. “Painful, almost afraid to say a word, but he eventually came around,” says his roommate in those first days, Stephen Harper.

McDavid watched his teammates and learned from those whose names won’t be remembered by anyone but him. He came to understand the necessity of leadership and the value of knowing your teammates have your back. On the bus it starts with him. He’s the Otters’ captain until he is something else.

McDavid’s few hushed words become chatter, become conversation. Five hours will pass in all. At the U.S. border a customs officer climbs onto the bus. At a pit stop, McDavid and Strome dash to get some fast food. As sick as McDavid and Strome felt after the loss, they were far sicker by the time the bus pulled up to the arena in Erie.

“Should we go to a hospital?” Bob Catalde was at the Otters’ final game with his 10-year-old son, Nico, but made better time getting back to Erie than the team bus. He put his son to sleep then stayed up, waiting for Connor.

“No, I’ll be alright,” McDavid says. “I’ve just gotta get to bed.”

“What is it?”

“Food poisoning, I think.”

McDavid is too sick to think about symmetry but it does occur to Catalde. Three years back he and his wife decided to take in players, and the first to occupy their basement were Harper and McDavid. A Buffalo-born real-estate lawyer, Catalde coached a local travel team and had read the stories in the paper about the kid who had been granted exceptional-player status. He knew enough about the game to sense that the player his family was billeting had a chance to be something special. But when Kelly McDavid dropped her son off with the Cataldes that night, he looked just like he did now: as white as a sheet and bathed in cold sweat.

That first time, Kelly told Connor she would stay another night if he wanted.

“I’ll get a room at the Sheraton and you can stay with me …”

“Mom, just go.”

Maybe it was the wisdom of a 15-year-old: The break has to be clean. Maybe it was the fear of peer pressure: that he would be endlessly chirped by older teammates. Have they cut the umbilical cord?

McDavid made it though that first night and he’ll make it through this one. He goes downstairs to his room and passes out as much as falls asleep. Even without the illness, there’d probably be no drifting off after the toughest loss of his life, the one that made impossible the last of the vows he made to his father at age 10: to play in the OHL at 14, to win a world junior gold and to win a Memorial Cup.

McDavid wakes in the morning and texts Strome, asking if he’s sick, too. “Barfing.” No emoticon. Knowing he’s not alone in his misery, McDavid falls back asleep, sweating the toxins out of his system. Nico is about to go down to the basement for a game of mini-sticks. Bob tells his son to let Connor be. “He’s pretty sick,” he says.

After breakfast but before lunch, Connor comes upstairs in slow motion. Food is offered and declined. “I don’t think I can keep water down,” he says.

“See how you feel by dinner then,” Bob says with no real hope.

The Cataldes had a plan for the day, Connor’s last in their home. Bob was going to do a big dinner, a celebration of all the remember-whens. Remember all those times you came out to Nico’s practices and got on the ice with the kids, or the games when you were behind the bench with me and you worked one of the gates?

There was no shopping for that last meal before game five in Oshawa—that would have been a betrayal. It would be a rush now, but Connor doesn’t seem up for it. He looks like he’s going to go back down to bed for another 12 or 24 hours.

“What time is it?” Connor says. “I have to get to the arena.”

The Otters are gathered in their dressing room at the Erie Insurance Arena for the last time. They have to clean out their stalls and throw their equipment in the backs of their rides home. It’s not like the pros. There are no reporters in their faces asking them what went wrong and what’s next. Still, they’ll have to kick around the still-warm coals of the season that ended the night before. Their last official obligation is an exit interview with the coaching staff. For the younger players, ones who’ll be back in August, Knoblauch seizes a teachable moment and passes on a message to take through their summer workouts. For the over-agers, those whose eligibility has run out, the meeting is bittersweet but still meaningful, especially if they’re looking to enrol with a Canadian university or land a free-agent tryout or minor-league deal with an NHL organization—if they need a good word put in.

An exit interview with Connor McDavid is a different matter. He sits down across from Knoblauch and his assistants, Vince Laise and Jay McKee, and all four do their best to ignore the pointlessness of the exercise. There’s no teachable moment now, or really ever, with a player like McDavid. The coaches have had to catch themselves in practice every day—McDavid doing something spectacular, making a whistle fall from Knoblauch’s lips and turning his assistants into fans. That stuff is learned but can’t be taught.

There’s no need to promise a reference that will never be needed. If he isn’t already, McDavid will become one of the most powerful people in the game. Those sitting across from him in the coaches’ office are more likely to benefit from knowing McDavid than vice versa. He’ll sign a sweater for a fundraiser or maybe talk to a talented kid the Otters are trying to recruit. “Thanks for everything,” Knoblauch says. “You’ve got a lot to be proud of, but you should know that you can be proud of being the captain of this team.”

Back in August, Knoblauch wasn’t convinced that McDavid should wear the “C.” The coach thought it might be piling on unneeded pressure. He never told McDavid what changed his mind and it might easily have been missed: A young goalie trying out for the team in training camp struggled in a scrimmage and was silently hanging his head in the dressing room afterwards. McDavid had only met the kid a day or two before, but he went over, sat beside him and talked him up off the floor. If he could empathize with a scrub, someone who might never even play a major-junior game, the “C” suited him.

For McKee, the thought bubble floats up as it has on a daily basis: He’s so Sidney. McKee played 13 seasons in the NHL, the last one five years ago with Sidney Crosby, then just 22, just after The Kid raised the Stanley Cup. On the ice McKee sees the parallels in their skill sets and, even more, their make-up. Off the ice and in the room, though, the similarities are even more striking: special talents who almost desperately avoid special treatment, or even the appearance of it; who want nothing more than to blend in even though they so conspicuously stand out; who are by nature reserved and humble, but by force of their gifts have to accept leadership roles and adapt. They have their differences, of course: Crosby seems incapable of taking a day off or giving as little as 99 percent in his off-ice work while, McKee says, McDavid doesn’t always bring it in the gym, much more like an average kid on that count. Still, unlike stars who don’t give a rat’s ass about anyone else (and they are legion), Crosby and McDavid care what people think of them, their teammates most of all.

McKee thinks about the one moment, the passage of two seconds, when it all kicked in. He can see it. We’re up a goal late and they pull the goalie. McDavid makes a play in the neutral zone, fleeces a defenceman, puck is knocked over to Remi Elie and there they are, on a two-man breakaway on an empty net, sorta side by side. Elie has it, and in a situation like that you give the puck back to the guy who made the play, but McDavid doesn’t let him. He’s skating beside Elie and keeps his stick in the air. He wants his linemate to get the goal, doesn’t give him any choice. And Elie has to take the shot because it’s still a one-goal game. Yeah, in a split second he thought of it. Just like Crosby would.

And when someone asks about McDavid coming in for his exit interview, McKee will say that he would never blow off anything like that. What would his teammates think of him? By coming in when he could easily have begged off sick, McDavid was reinforcing the coaches’ authority.

McDavid has packed up and wants to leave early, worried about getting tired or getting sick again on the four-and-a-half-hour drive, wanting to get to the border before dark and before the deer start dancing across I-90. Dinner at the Cataldes’ is off. Not the way it was supposed to end but those are the breaks.

Bob Catalde knows that Nico is going to take it hard. No more going downstairs to play mini-sticks or Xbox with Connor in his basement apartment. No more pulling the net out into the driveway or onto the street of the cul-de-sac.

Connor hugs Bob’s wife, Stephanie, his daughters, Caisee and Camryn, then Nico, and then finally Bob walks out to the car with him. Bob offers: If he wants to stay the night and rest, he’s welcome to, but no, the exit has to be as clean as the arrival. Given the way events played out a few weeks back, though, this break feels a little more dramatic. It would have been so much easier if Buffalo had won the lottery. Bob would have put in for season tickets that night. Connor would be an hour and a bit down the road. Even if it had been Toronto, the Cataldes could have stayed in touch, followed him and visited. A selfish wish, maybe, but one that was shared by many in the McDavid circle over the last years in Erie: that he would just move up rather than away. Now the Cataldes were only going to be able to go a couple of games every winter, and Nico won’t be staying up late to watch those late Western Conference games, not until high school. “We’ll see you at the draft,” McDavid says.

Bob hasn’t told Connor that he and his wife have talked it over: They won’t billet another player next year. It’s not that it was trouble. It wasn’t. Not when the reporter and photographer from the New York Times were knocking on their door. Not when the camera crews were walking through the house. Not even when gawkers drove a loop of the cul-de-sac to see exactly where it was he lived. No, it was just… intense, that’s the word. It might be a cliché but it’s true: Connor has been like a brother to Nico, and it’s tough to start that all over again. The Cataldes will take a break, at least next season, before bringing another Otter into their home.

When everything is in the trunk and the backseat, Catalde wraps a hug around Connor, says nothing and sobs.

It’s Tuesday morning after the Victoria Day weekend. Brian, who has been fighting some sort of bug, drops Connor off at Sir William Mulock Secondary School, a bright, newish institution populated by laptop-carrying suburban teens, home of the Black Ravens and, if Wikipedia is to be trusted, a kick-ass Ultimate Frisbee team. Exams start in a couple of weeks and Connor could work from home if he wanted, but instead he’ll be sitting in classrooms beside kids he has known since grade school—he didn’t want to be around the house all day. The set-up is routine for Otters players who are high-school age: In the first semester they attend McDowell, a public high school five minutes from the Cataldes; in the second semester, starting in January, they commence online courses through schools in their hometowns, so they can parachute into classrooms when they go back. In his three years with the Otters, Connor’s school year has never gone off quite as planned, though, what with various hockey-related field trips interrupting.

Finishing The Grapes of Wrath, he’ll have scratched all his English assignments off his list. He still has projects and exams left in Social Justice (reading gender equity) and History (reading Ancient Rome), though, and his past Scholastic Player of the Year awards won’t matter much if he applies to a school down the line and hasn’t tidied up his remaining courses.

His standard line: “I’m not going to live to be that typical jock stereotype.” Variations on this include “dumb jock.”

When asked why this is a priority, he’ll put that desire down to pride, but 18-year-olds, even scholarly teens, aren’t long on introspection. His parents see it as a matter of competition, him versus a given subject. It might run deeper than that. As a grade-school kid he competed against Cameron in everything, and his older brother had a four-year head start. He grew up playing up. It wouldn’t matter if it was on ice, on the pavement or on a game board laid out on the dining-room table. Competition had no boundaries and Connor didn’t relent. Cameron is a very good student—with his degree from the Ivey Business School, he has a wealth of options, law school among them. His little brother has to match and better him.

“Connor. Connor. Connor.” Kids chase McDavid and adults either follow or encourage them to pick it up and run him down on the concourse of the Colisée. The Memorial Cup semifinal between the Kelowna Rockets and the host Québec Remparts is tied one-all after the first period and McDavid has to make his way from his seat to the upper bowl where the panel’s desk and cameras are set up.

He stops. He signs. Cameras flash. The crowd buzzes and swells. This is the lot of the selfless star in the age of the selfie.

McDavid has mixed feelings, not just about being a celebrity but about celebrity itself. At some level he just doesn’t understand the fascination—never has. In the McDavid home, there’s a picture of Connor standing between Nos. 66 and 87 on a trip from Erie to Pittsburgh. That one is kept out in the open. But there’s another, more telling shot somewhere around the house, in a drawer or a box: Connor age 10 with Mario at the Quebec Peewee tournament, back when he was playing with the York-Simcoe Express. His father coached the team that season and in the hallway outside the dressing room before a game, Brian saw kids lining up to get their pictures taken with No. 66 like tourists with Bonhomme de Neige. Brian went in the room and told Connor he should go out and get one for himself. Connor balked. “We have a game to get ready for,” he said. Brian told him it was OK. Connor said it wasn’t. It went back and forth until finally Brian physically picked his son up and carried him out to the hall, plopping him beside Lemieux. At that point, Connor realized that he couldn’t make a scene, but he stood there only long enough for the photo, the smiling Hall of Famer next to an unimpressed 10-year-old doing Grumpy Cat.

“It’s a true honour. You look at all the great names across the country to play in the CHL. To be recognized as the player of the year is so amazing; something you kind of dream of.”

“We’re good,” the guy holding the microphone says. The light on the camera goes dark. The video will be up on the Memorial Cup website minutes later. McDavid walks over to his parents and Strome, who are dipping into the hors d’ouevres at the CHL Awards reception at the Château Frontenac.

McDavid has a comfort level on camera—with one painful and instantly infamous exception. He’s just a few weeks removed from the NHL Draft Lottery, broadcast live on Hockey Night in Canada. A camera was trained on McDavid as he walked through the studio and onto the set and it captured his reaction seconds after Deputy Commissioner Bill Daly revealed that the Edmonton Oilers had bucked the odds and landed the No. 1 pick yet again. Many read that reaction as disappointment that he was headed where teenage talent goes to stagnate or wither. His blue suit, it was argued, subliminally advertised his desire to go to his hometown Leafs. Or he had looked at the rosters and decided Buffalo or Phoenix would be a better fit. The common message: Edmonton didn’t win the lottery; McDavid and the NHL lost it. Viewers thought the worst of him, even though just seconds before he was interviewed, Oilers assistant GM Bill Scott refused to rule out a possible trade of the first-overall pick or the selection of another prospect.

McDavid had gone out of his way to appear on the broadcast—he and Strome had driven up from Erie that day—and if it wasn’t an outright disaster, it was a bit of a mess. “If I could do it over, I would do it differently,” McDavid says now. “Not with the camera on me the whole time.”

At home, at the arena, with family, friends, celebrities or strangers, McDavid is the same: soft-spoken, almost painfully so; matter-of-fact if not phlegmatic. He sounds more like a musician or an artist than an athlete—someone content to let the work speak for itself.

The Oilers will figure that out in time, but likely haven’t yet: Just days out from the Draft Combine, the team hasn’t contacted him nor his agents. “If they take me, I know that they bring in rookies Tuesday right after the draft,” he says.

If they take me. McDavid seems not to have read anything written about him nor heard talk about the “McDavid sweepstakes.”

More ifs follow. When asked about the challenges that await him playing in the NHL next season, he’s demure again: “Can’t really say that for sure. I could be back in Erie and playing another season of junior.”

Like all other prospects for the draft, McDavid filled out a questionnaire for NHL Draft Central Scouting Service. On the line beneath “Ambition outside of hockey” he printed: “I would like to be a lawyer if my hockey career does not work out.” And while NHL GMs and scouts mention him in the same breath as Gretzky and Crosby, on the questionnaire McDavid compared himself to a player in an entirely different category. “I think I am comparable to a player like Tyler Bozak because he is a good skater and is more of a pass first type of guy.”

Those who know McDavid say these answers are entirely consistent with his personality: He sees himself differently than anyone else because he thinks of himself as no different from anyone else. Stephen Harper, the one who wore the Erie sweater, often tells a story from McDavid’s rookie camp: “He had come in as an exceptional player and is the first pick in the draft, signed a contract with the team, everything, but when we go on the ice he’s wearing his [Toronto] Marlies stuff because, he says, he ‘hadn’t made the team yet.’ And that’s just how he is. He doesn’t presume anything.”

This goes a long way to explaining his reaction on the draft-lottery show. It could have been that he wasn’t uncomfortable with the idea of going to Edmonton so much as Strombo’s suggestion that he was automatically going No. 1. After all, McDavid went to Erie when the franchise was regarded as the league’s worst, when other top prospects had advised management that they wouldn’t report if the Otters drafted them. He went from a Marlies team that won more than 70 games and lost just three in a season, to an overmatched doormat that practised in an Erie arena where the ice was cracked, uphill in one end and banked like a motor-speedway along the boards. He’s the antithesis of the entitled hockey brat.

Because of the heavy weather of a long season, because of tempests like his broken hand and his appearance on the draft-lottery show, McDavid needed to go back where he’s been and back where he’s from. He needed time to say thanks to the people who looked after him. He needed time at home, where the net he shot on in the driveway still leans up against the side of the house.

But here in Quebec, in this meeting room at the Château Frontenac, sponsors, officials and executives line up to shake McDavid’s hand and talk to him. He would sooner hang out with Strome and the other players, sooner watch a playoff game, sooner kick back and play Xbox. But duty calls. A television camera and photographers follow him. Everyone in the room knows that riches and fame await him, and they will read something into his every word and deed, all of them wanting just a minute of his time. Brian and Kelly McDavid knew this day would come, the onset of another level of stardom: Their son had made the impossible look everyday for years and now, finally, it’s the everyday that has become impossible.