The first nine months of 2014 were difficult for Devan Dubnyk. While hardship followed his departure from Edmonton, he didn’t realize at the time that he had actually been rescued from a firing squad.

Last season was a disaster for Dubnyk and one that I highlighted in November while looking at the environment that lead to Ben Scrivens’s struggles this season.

Scrivens experienced Dubnyk’s journey in reverse as he went from the highs of a strong team structure in Los Angeles to the chaos of a defence lead by Justin Schultz, but there are parallels. It is easy to understand how things can snowball when forced into recovering from continuous broken plays and the difficulty of maintaining the discipline not to cheat. Dubnyk looked lost at the tail end of his Oilers career and seemed to have lost all confidence as he bounced from Nashville to Montreal to Hamilton.

And then goalie voodoo.

Theories began to point to Sean Burke being a goalie whisperer and turning Dubnyk’s game around upon arriving in Minnesota by teaching him the inside-out approach to goaltending preferred by Henrik Lundqvist and Mike Smith. I don’t doubt that Burke helped in rebuilding Dubnyk’s confidence, but if the inside-out approach is the cure-all for large goaltenders, then Burke needs to whisper some more into Smith’s ear because he has been struggling badly since his one great season in 2011–12.

The second theory—and one more structured in logic and goaltender education—was Dubnyk being taught a new technique called head trajectory by former New York Rangers goaltender and current MSG personality Stephen Valiquette. It’s a new way of tracking the puck and was developed by Lyle Mast, the founder of Optimum Reaction Sports.

Sportsnet Magazine Stanley Cup Playoffs

Sportsnet Magazine Stanley Cup Playoffs

Edition: The six reasons why Carey Price can take the Montreal Canadiens all the way. Download it right now on your iOS or Android device, free to Sportsnet ONE subscribers.

Technical greatness should be the goal of every single NHL goaltender who straps on pads, but I have witnessed goaltenders who are technical messes like Tim Thomas produce a .938 SV% and Carey Price, considered the greatest technical goaltender in the NHL, drop a .905.

So I look to environment.

While reviewing Dubnyk’s last two seasons, I noticed the same kind of extremes as Scrivens. Interestingly enough, Dubnyk’s numbers in Edmonton were significantly below the expected .905 and his results in Minnesota were way above the expected .922, but when the two season samples (including his time in Arizona) were merged, the large sample placed him at slightly above average.

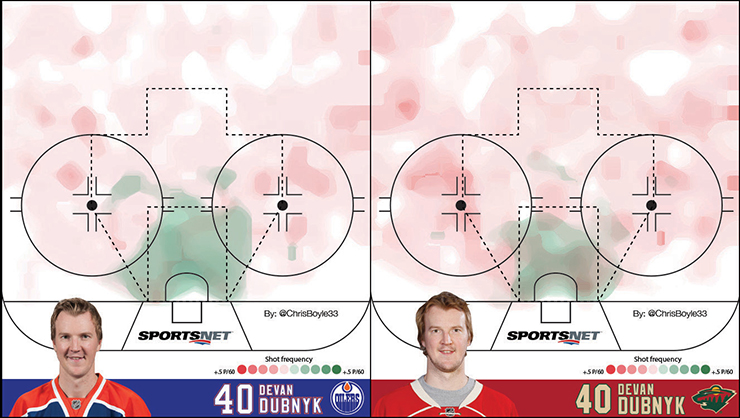

We can see visually why Dubnyk struggled in Edmonton. I have slightly altered my heat maps to separate all pre-shot movement against clean shots, creating some consistency with the terms that Stephen Valiquette has been using through his work at MSG. The green area represents higher-quality opportunities and the red area lower-quality opportunities.

In Edmonton, Dubnyk was bombarded with high-quality slot opportunities. Forced to set and judge depth while on the move is a recipe for disaster and Dubnyk—like Scrivens and Viktor Fasth—wasn’t equipped to handle this type of volatile environment. Just over 80 per cent of Dubnyk’s looks in Edmonton were clean. Contrast that to Minnesota where his clean looks went up to 88 per cent and Dubnyk’s size became an asset again. This accounts for the .017-point differential in expected SV% differential.

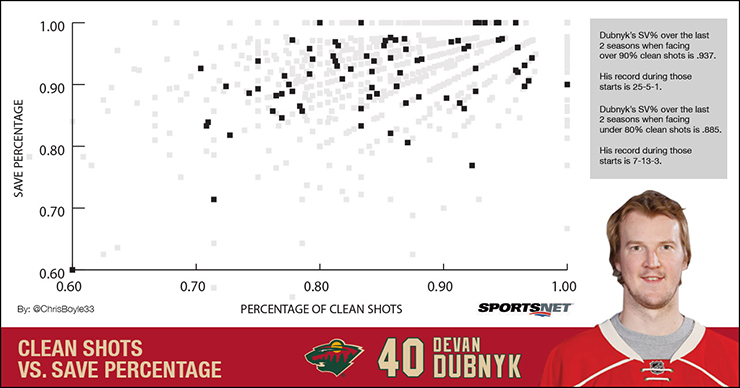

When I started this project, one of the things I did was track individual games and the effect clean looks had on save percentage. The more clean looks, the more success.

Dubnyk is no different. If he gets defensive support and is allowed clear sight and the ability to set his depth and angle, he has more success. When the defensive structure in front of him clears shooting lanes and clogs passing lanes, Dubnyk is a .937 goaltender—when they fail to do so he becomes an .885 goaltender.

We make assumptions that goaltenders control their destiny, and to an extent they do. The position is a random set of math problems being fired at them at 100 m.p.h. and their job is to judge distance, angle and velocity, and attempt to read and recognize the problem scenario before it happens. It is why the mental aspect of the game is so important. If you have all the technical greatness in the world and your recognition is poor, you will position yourself for a scenario that isn’t going to occur. The elite goaltenders in the NHL are able to do both and get maximum coverage for most scenarios even when things breakdown.

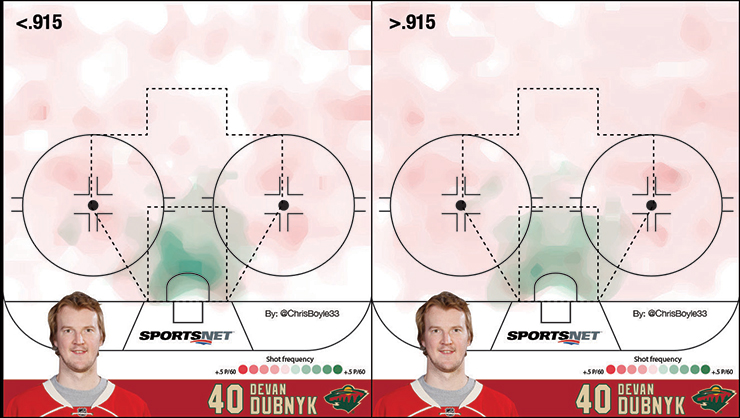

The problem: Some goaltenders get more fifth-grade-level math problems and some are tasked with solving the Kobayashi Maru. We can see this with Dubnyk. When we separate the games where he failed and where he excelled we see that success in these scenarios isn’t random.

The “good start” and “bad start” labels imply that the goaltender is fully in control of the result. Over the last two seasons I separated the shots when Dubnyk was considered to have been successful and starts where he would have been attached blame for failure. The chart on the left is below-average results—the chart on the right above average. Just like the Edmonton/Minnesota split, the more pre-shot movement he faced, the less success he enjoyed. The more clean looks from the perimeter he faced, the higher his save percentage.

Through two full seasons of advanced goaltender data, Dubnyk grades out around average, right in the NHL middle-class. This matches up closely with his career save percentage of .914.

The important question that can be answered as I gather more data is whether the Oilers were a .905 team while he was producing save percentages of .914 to .920. If Dubnyk was actually a +.010 above-expectation goaltender, then he was merely a small-sample failure on a team lacking defensive structure and is everything that management should be looking for in exploiting a market inefficiency.

The Minnesota Wild admitted that the Dubnyk acquisition was born of desperation, but identifying players like this is the driving force behind analytics. The first team to separate the defensive noise from actual goaltender performance will have a window where they can pick and choose undervalued goaltenders on the NHL market as well as raid major-junior at minimal cost.