As you probably know, Jacob Trouba made a public request to be traded out of Winnipeg two months ago. After going unsigned as a restricted free agent into the start of the season, he finally came to terms on a very affordable two-year, $6 million contract that should make him appealing for any trade partner.

The question that both the Jets and their prospective trading partners need to answer is simple: What is Trouba worth, or put another way, how good will the 22-year-old rearguard be in his prime?

Traditionally, the only available answer to that question came from scouting. Trained eyes would monitor a player’s skating, ability with the puck, strength in front of the net and myriad other qualities and then project the player’s future development. Trouba, a big, mobile defenceman who plays the game with an edge and can handle the puck, typically fares well in such assessments.

For the most part, it’s an effective approach. NHL teams routinely take on the Herculean task of assessing draft-eligible players much younger than Trouba, and the league as a whole does a good job of sorting teenage players by skill. But in a competitive environment where even marginal gains can make a big difference, there’s every reason to look for an edge, which is where the extra data offered by analytics comes in.

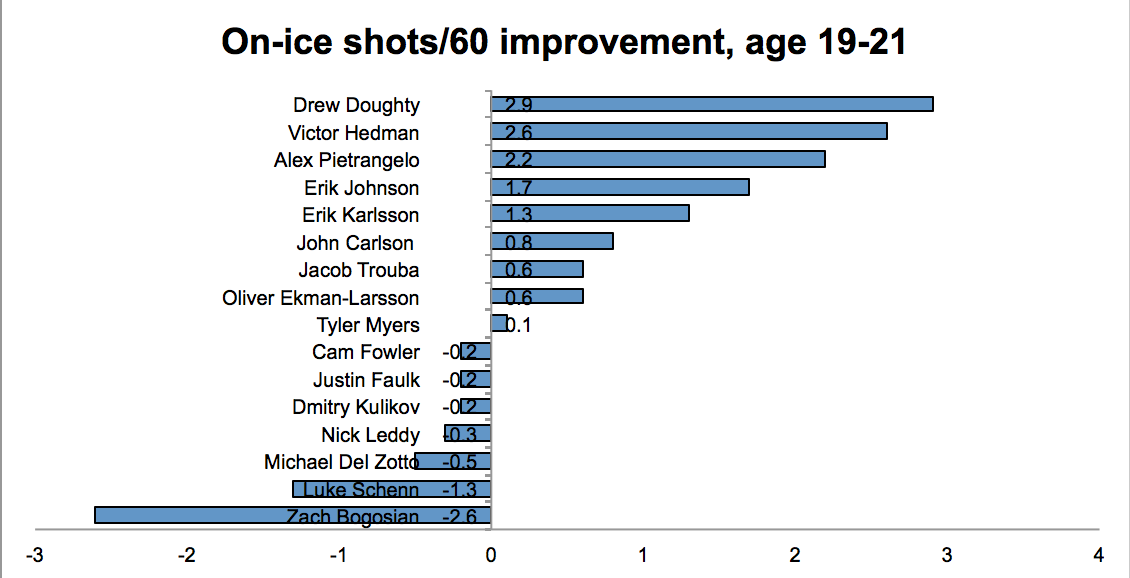

We start with a list of players who, like Trouba, played significant NHL minutes between the ages of 19 and 21. But we limited this assessment to the post-2007 period because that’s when these statistics first became available. We then sorted those players by how much better (in terms of shots per hour) their teams fared when they were on the ice in 5-on-5 situations. The result is a remarkably good indicator of how these players would turn out in following seasons:

At the top of the list are Norris-type defencemen, players such as Drew Doughty and Victor Hedman, who even at a young age drove shot differential for their teams. With the exception of Erik Johnson (who belongs in the second tier) every player listed who improved his team by at least 0.5 shots/hour would end up turning into a great defenceman. Trouba showing up in that part of the list is a very good sign.

Players who didn’t drive shot differential at a young age generally have enjoyed less stellar careers. The break-even types in the middle of the chart include a bunch of good but not great defencemen, such as Cam Fowler and Tyler Myers. It’s a little early to tell with Justin Faulk, but he may buck the trend and climb into the Norris group at the top of the list.

Luke Schenn, unsurprisingly, comes in near the bottom of the list. Zach Bogosian is in last place, which seems low given the career he’s had, but is quickly explained when we switch to a look at situational factors.

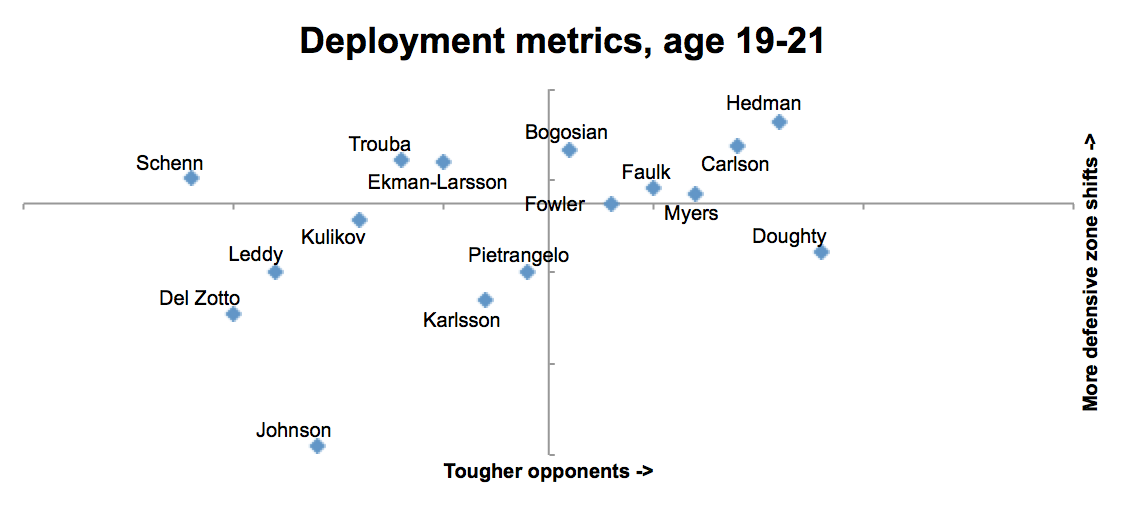

Going from left to right, the scatter plot above shows quality of competition (based on the average ice-time of each player’s opponents), with the guys facing the toughest opponents on the far right. From top to bottom, we see which players got a lot of shifts starting in the defensive zone, with the toughest minutes at the top and the easiest at the bottom.

The extent to which quality of competition and zone starts influence shot metrics is still debated within analytics circles, but there’s little doubt that at the extremes they tend to matter more. Thus Bogosian, who faced tough opponents and zone starts, has some excuse for his wretched shot metrics. At the other end of the spectrum, Erik Johnson was sheltered like no other player on this list, which helps explain why at first glance he was hanging out with the manifestly superior Erik Karlsson and Alex Pietrangelo.

If we draw a diagonal line from the bottom left corner (easiest minutes) to the top right corner (hardest minutes), Trouba comes pretty close to the mushy middle; he hasn’t been thrown to the wolves nor coddled by his minders. His shot metrics are a study, too; he’s right on the heels of John Carlson and Oliver Ekman-Larsson at the same age, but he also isn’t far clear of Tyler Myers and Cam Fowler.

This is where it’s worth mentioning his defensive partner. Winnipeg’s deficit on the left side means that Trouba has spent more than half of his early career playing on a pairing with depth defender Mark Stuart — and when he hasn’t, he’s often been forced to switch to his off-side.

Stuart has a long history of getting out-shot in the NHL. In all but one season of his NHL career his team has been out-shot when he was on the ice. The lone exception was 2014-15, when he spent 80 per cent of his time with Trouba and posted a 54% Corsi rating in those minutes. In the other 20 per cent of his time he had just a 47% Corsi rating.

Offence is worth considering, too. Trouba’s point totals have trended down over his three-year NHL career, and his scoring rates both at 5-on-5 and the power play are unimpressive when compared to the other players on this list.

Trouba’s shot metrics suggest he’s on the fence between being a good and great two-way defenceman, with either outcome possible. He lacks the offensive flair of the top-end producers considered above, but he also played with a less effective partner than most of those defencemen.

The prudent approach for a prospective suitor is to bank on Trouba developing into a very good but not elite defenceman and paying accordingly. He’s proven significantly less than players such as Hedman and Doughty and isn’t as sure a bet as they were at the same age. Yet there’s upside in such a bet, because his performance has been good enough that a high-end career cannot be ruled out.