It’s mostly the voice that gets you get up / And mostly the voice that gets you buck. — Gang Starr

The tempos and rhythms of a hockey game are not just complemented but heightened when paired with the right play-by-play man.

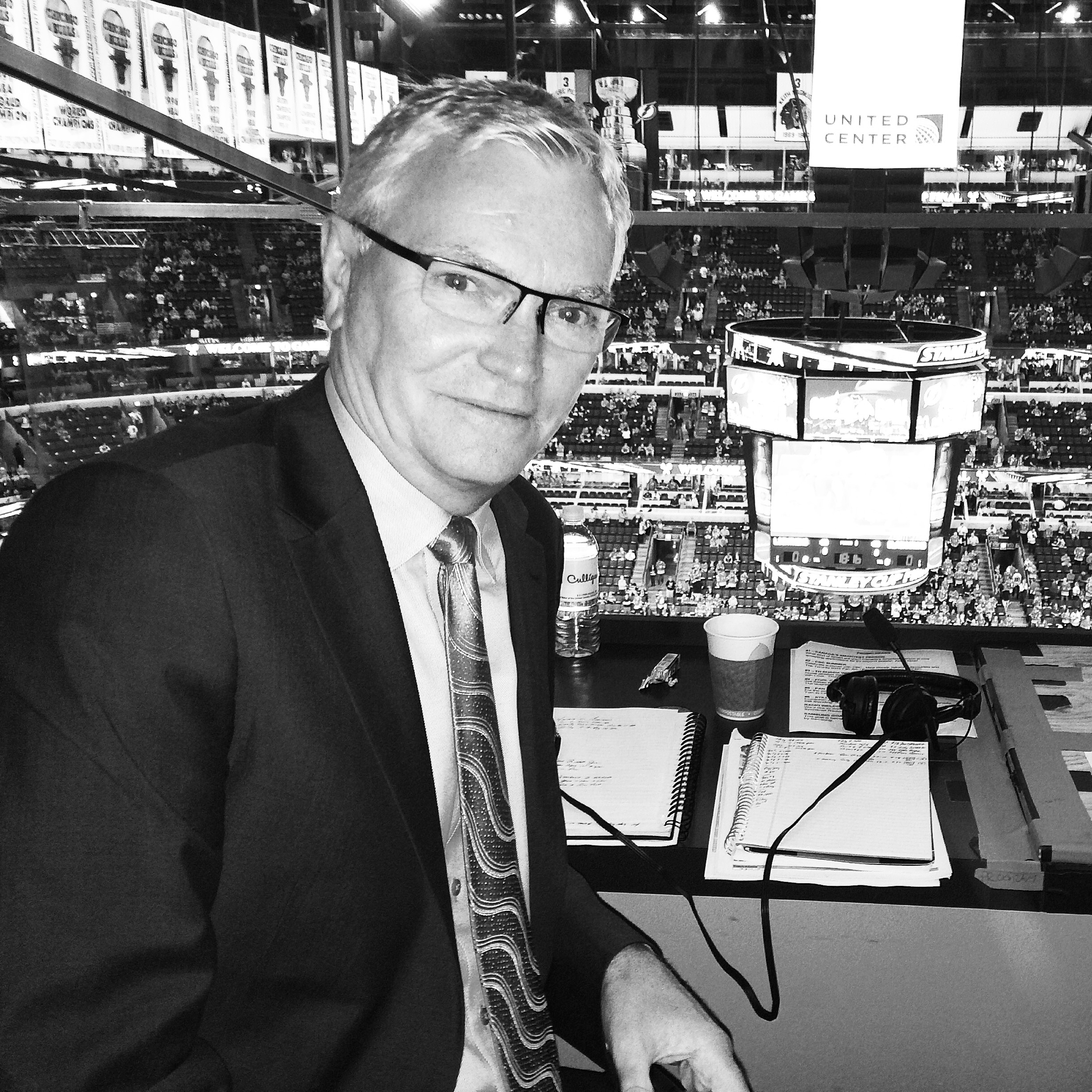

Jim Hughson, 58, has served as on-ice tour guide for Vancouver Canucks fans since the early 1980s.

For the last seven seasons the B.C native has been Canada’s soundtrack to the Stanley Cup Final, after working his way up and taking the baton from Bob Cole as the No. 1 booth man on Hockey Night in Canada.

Hughson has done a bunch of other cool things, like commentating EA’s massively successful NHL video game series, making Toronto Blue Jays games sing, and appearing in 2000’s monkey-on-ice cinematic classic MVP: Most Valuable Primate.

The day he called the 2015 Stanley Cup championship game in Chicago, we discussed the craft of play-by-play, why he’s not a fan of catchphrases, and how the repair guys recognize him by just his voice.

It’s mostly the voice.

READ MORE: Q&A with NBC’s NHL voice Mike “Doc” Emrick

SPORTSNET.CA: When did you know you wanted to call games?

Jim Hughson: Nothing was preordained. I went to university, didn’t finish a degree, went back to work in the radio business. I just wanted a job. Just moved around making $50 more a month where I went to.

When the opportunity came to move to Vancouver at a big radio station, I jumped at the opportunity and started working before I found out how much money I was going to make. I got the opportunity to fill in for [Canucks voice] Jim Robson. When he would do television games on Hockey Night in Canada, I would do the radio games. That was the first time I thought: This could be really cool. I like the idea of working in the winter and doing hockey games and play-by-play. I’d done some of that in junior. I also liked the idea of having the summer off.

SN: Does calling a championship make you nervous?

JH: I don’t think it’s a nervousness; it’s an awareness. There’s a real clarity, especially in the playoffs. You want to do a real good job; you want to know exactly what’s going on and not miss anything. It’s a nervous energy. You can feel it in the building; you can feel it in the teams. It’s not similar to playing, but there’s a real heightened awareness of what’s happening.

SN: What is your pre-game routine?

JH: By the time the playoffs come, I’ve seen all the teams. I know quite a bit about them. As the series go on, each game is like a mini drama, a show on its own. It’s really hard to prepare for them. What you do in the playoffs is you watch the games. I make notes to prepare for some things statistically, and I look over a lot of news and analytics stuff to see if it tells me what I think I saw. Usually it does.

My routine is different. Today I took the morning skate off because I wanted to go for a long run along Lake Michigan. My routine always includes a workout to be ready to call the game.

“I don’t think it’s a nervousness; it’s an awareness. There’s a real clarity, especially in the playoffs.”

SN: Do you mentally prepare what you’re going to say for a big moment, like a Cup or Olympic win?

JH: I don’t try to think of something original because for years what we say works. If you watch the videos, what you hear works. If you listen to the last minutes of the Cup games, like: “The Boston Bruins have won the Stanley Cup.” Those sort of lines, they fit all the time. Why try to invent something new?

You try to be ready for the end of the game, but you don’t know what that’ll bring. Los Angeles in 2014 was overtime, and it was a spontaneous reaction, a far more excited reaction. The first time in L.A., we didn’t say anything. We had been silent for three minutes at the end of the game because the decision had been made. They were ahead of New Jersey, we knew they were going to win, and they were at home, so you just let the fans take it.

SN: Is that your decision, or does someone in the production truck advise you to be quiet?

JH: I talked to our guys beforehand. Basically, we as a group always say that if the home team is ahead and there’s nothing left to be said, why? Just turn it over to the director, let him take shots and let the audio guy ride it. So I didn’t say anything until the game was over, the pileup was on, and we had shots of the excitement everywhere. I just added: “And here are the words that have never before been spoken: The Los Angeles Kings have won the Stanley Cup.”

SN: How do you succeed Bob Cole? He was The Man for so long.

JH: My profession is no different than the players’: You want to be working on the last day of the season. And the only place where I could do that is at Hockey Night in Canada. I was there for several years before I got the opportunity to do that. It was good. You want to have the honour of calling the last game when the horn sounds at the end or the goal goes in at the end of the season.

SN: Did you have a conversation with Bob when you were promoted?

JH: We haven’t spoken a lot. It’s like a lot of play-by-play guys—you never see them because we do the same job. When I’m working, he’s working.

SN: Describe how you dealt with Patrick Kane’s confusing Cup-winning goal in 2010.

JH: That was so bizarre. There were only two places the puck could be: under Michael Leighton’s pad or in the net. I had to make a real snap decision whether I believed Patrick Kane, because he was the first one reacting. And he reacted like he’d scored the goal. After the pause and wondering where the puck was, I decided instead of saying something like, “Where’d the puck go?” I decided to believe him. He was celebrating like he knew exactly where the puck was. He went down to the other end, and we were still trying to find the puck.

Not everyone was convinced they’d won the Stanley Cup. Even guys on the Chicago bench and the players wanted to celebrate, but they kept looking back for someone to confirm they’d won. It was pretty crazy. That’s the beauty of live sports—you never know what’ll happen.

It was an interesting night afterward. I talked to guys who do the same job I do for other networks—everyone was in the same boat. Guys had the same problem: They couldn’t find the puck.

SN: What is your favourite hockey phrase?

JH: I never thought about that. I do know if I ever get into saying catchphrases, things I say too often, I abandon them. I don’t need catchphrases, and I’d rather not be known for a particular phrase, so I’ll change it. I prefer the old phraseology of hockey. I don’t call the boards the wall. What’s wrong with the boards? They were always fine with me.

SN: Celly?

JH: Not into that. Things like he elevated the puck. Well, raise was a pretty good word for a long time. He’s activating his defenceman. No. The defenceman jumped into the play. I’m not sure why we started to change all this stuff. Back-checking became back pressure. I prefer the basic stuff, the simpler form.

SN: How do you stay sharp? How much of calling a fast-paced game is innate ability and how much is just repetition?

JH: I think a lot of it is reps. I guess it’s a hard thing to do because there’s not a lot of guys that do it and are good at it. I realize you have to work at it. The biggest thing for me is: watch the game, understand the game. If you watch it long enough, you’ll understand what’s unfolding in front of you. And if you understand what’s unfolding, it’ll slow down for you. Knowing who’s on the ice, knowing what they probably want to do with the puck, knowing who’s the key man on the power play. Sometimes there are changes on the fly you can’t see, like who’s come on to play the right wing, but if you trust yourself, you know who that right winger is because of whose line he’s on or you know how he skates, so you don’t need to wait to see his number. That’s repetition, repetition, repetition, watching a million games.

“If I ever get into saying catchphrases, I abandon them.”

SN: You called plenty of baseball in your day. How is the approach different with hockey?

JH: I went back and forth between them. They’re so very different. You have to psyche yourself up for a hockey game because you know it’s going to be fast and over in a hurry. Baseball, you’ve got to be ready with all sorts of anecdotal information and stories because it’ll meander along forever. I love them both for how different they are. You prepare differently, but you have to be aware of what’s going on—that doesn’t change in any sport. I’m convinced of that.

Young people ask me how to get into this business, and especially in hockey they think the difficulty is memorizing all the names. Simple memorization is the easiest part of the job. Everyone does something in their job that is redundant, that they do without thinking about it. Mine is knowing the players.

Knowing what you’re watching and understanding the game is the difficult part. You never master it. Because the game is changing. Guys are finding new ways to play it. In a playoff series they make adjustments and find new ways to beat an opponent. The difficulty is understanding what they’ve done and how they’re doing it.

SN: When you call to order a pizza, does the guy at the pizzeria recognize your voice?

JH: Often. If you’re phoning a repairman to get something done, the guy on the other end will pause for second and say, “Is this the Jim Hughson I think it is?” At one point I was doing the EA Sports games, and I had people in the U.S. who would recognize my voice and they’d ask, “Do you call real games or just video games?”

SN: Best moment you’ve had the chance to call?

JH: The Olympics in Sochi was spectacular. I would not differentiate any one Stanley Cup from another. Just to have the voice of record for a Stanley Cup championship game is pretty cool. The Canadian team in Sochi is the finest team I’ve ever watched play hockey. To see the whole world of hockey—the best from all over—and to see how far it’s come, how much better it is, even though there are one-sided games, is pretty cool.

SN: Any European name that always trips you up?

JH: New guys. I remember the days when the Russians first sent their touring guys over here and they’d play NHL teams, they had no PR people with them. There was no way of figuring out how to say a name, so you’d ask somebody you thought was from Russia—some guy covering the team from a Russian newspaper. Doing the video games, I’m sure there were a million mistakes with the foreign names, but after a while I got the Swedish and Finnish and Russian names down. The syllables follow a similar pattern, so you can guess your way through it. Then you get to the Olympics and you run into Sabahudin Kovacevic. Never heard of him before, and there’s no one to ask.

(photo by Luke Fox)