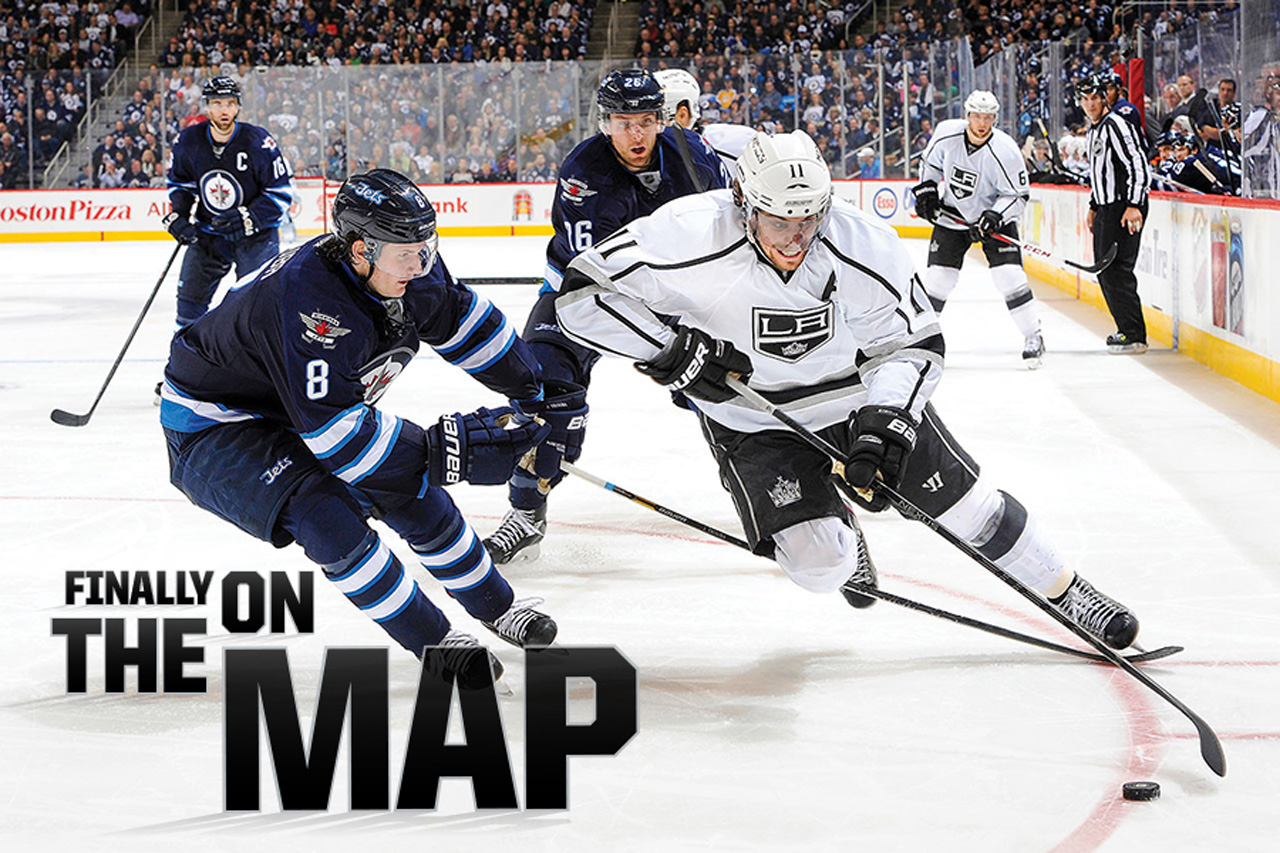

Two Stanley Cups and 550 points into his career, Anze Kopitar is the pride of Slovenia. And the NHL’s most underrated superstar.

By Dan Robson in Los Angeles

he first time Anze Kopitar brought the Stanley Cup to Slovenia, thousands of fans packed into a soccer field in his hometown, where a stage was erected in his honour. He was driven through the crowd in a horse-drawn carriage as fans stretched their arms over the top of the people in front of them to try and snap a picture of the local legend with his silver mug.

he first time Anze Kopitar brought the Stanley Cup to Slovenia, thousands of fans packed into a soccer field in his hometown, where a stage was erected in his honour. He was driven through the crowd in a horse-drawn carriage as fans stretched their arms over the top of the people in front of them to try and snap a picture of the local legend with his silver mug.

They chanted “Anze, Anze, Anze,” and a row of young hockey players on the stage tapped their sticks in salute. Kopitar hoisted the Cup high above his head and all those in attendance pretended to lift it with him. It was the first time a player from Slovenia had won the Stanley Cup, and the first time hockey’s grail had visited the picturesque nation of two million that borders Austria, Croatia, Italy and Hungary. Many of those people had stayed up through the nights to watch Kopitar and the Los Angeles Kings battle the New Jersey Devils in the 2012 NHL final.

He was a national hero, an icon—the “wonder boy,”as local media called him. “It’s kind of like Brad Pitt walking around here,” says Justin Williams, Kopitar’s longtime Kings teammate, who visited his friend’s hometown the summer they first won the Cup. “Everyone knows who he is.”

For nearly a decade, Kopitar has been one of the best all-around players in the game. And yet, it seems, not everyone knows who Kopitar is. Playing on the West Coast in a city of stars, his local celebrity is naturally muted. And though he’s been one of the most consistent and effective two-way centres in the game, he is routinely left out of discussions about hockey’s greatest players.

If there is indeed a traditional-puck-market bias in the collective hockey conversation, Kopitar is its biggest victim. Nearly a point-per-game player since he entered the league as a 19-year-old, Kopitar is also one of the game’s most reliable penalty killers and his possession numbers are exceptional. Yet he has never won a major NHL award—aside from those two Stanley Cups.

“I think Anze Kopitar right now is the third-best player in the National Hockey League, only behind Crosby and Toews,” said Wayne Gretzky during last season’s playoffs. “And he’s getting better every game.”

Matjaz Kopitar, Anze’s father, exhales in appreciation when the Great One’s analysis is relayed to him over the phone in Slovenia. “Who would know, if not him?” he says. “It has to be true.”

In a quick survey of the Stanley Cup champions at the team’s practice facility near Manhattan Beach in Los Angeles, the dressing room is clearly in agreement with Kopitar’s dad: “I’m sure if he played in Canada or New York or Chicago, he’d probably get more attention,” says Kings captain Dustin Brown.

“He takes pride in defence,” says Drew Doughty. “In five-on-three he’s one of our first killers. In five-on-four he’s one of our first killers. At the end of the game he’s out there. That’s what separates him from other guys.”

But the most insight into what fuels Kopitar’s success comes from a man known for brevity. When Darryl Sutter first joined the Kings, he underestimated Kopitar’s ability—like many do. But he quickly learned that his front-line centre had a “special insight” into the game. Players like that, Sutter says, can help their coaches more than their coaches can help them.

Since Sutter’s realization, Kopitar and his coach have become close. Over the past few years, Kopitar has developed a connection with Sutter’s son, Chris, who has Down syndrome. They talk about basketball and shoot hoops together after practice sometimes when Chris comes down to the rink. Recently, the 27-year-old Slovenian told his coach that he and his wife—whose name, Ines, is tattooed around his ring finger—are expecting a baby girl. It was an emotional conversation, Sutter says.

“You can see the way he is with his family, with his wife—it’s special.”

That connection—to family and home—is the foundation on which Kopitar has built a career that seems destined for the Hall of Fame. And it helps that hockey has always been part of the family lexicon. “There’s good reason why he has so much knowledge about the game. He was raised in the rink,” Sutter says. “He’s been learning it since he was little.”

When he was just a boy, Kopitar watched every move his hero made—how he moved, how he passed, how he shot the puck. He studied every play in the man’s two-way game. Barely old enough for school, young Anze sat in front of the television in his family’s two-storey home in Hrusica, a small steel town in northern Slovenia on the border of Austria.

Kopitar imagined himself on that ice, carving past his opponents and filling the net while the thousands roared—just like they did for his hero. Kopitar had heard of other players, sure: Gretzky, Hull, Lemieux. But they were only characters in his imagination, outlined by numbers in the sports pages and tall tales of greatness. This man, though—this hero—he could see. And so, when Matjaz Kopitar, a goal-scoring left-winger, threw his hands in the air in celebration of winning the Slovenian Ice Hockey League championship for HK Acroni Jesenice—as he did three straight times from 1992 to 1994—his son Anze did, too. And the boy hoped to be like him, the greatest player he could dream of.

Kopitar learned the game when he was four, on the ice rink behind their house, built by his father and grandfather. As he grew, he laid the foundations for his snapshot and quick hands, putting his younger brother, Gasper, in goal as they played for hours into the night. If Dad was home, he’d be out there, too—watching, instructing. If not, he’d be on TV, playing his role as a national hockey icon.

Slovenia was technically young then, having secured independence from Yugoslavia in 1991. It was free and immensely proud. And it was small, measuring 20,000 square kilometres, with just six rinks within its borders. But fans were mad for hockey. The arenas would overflow for games between Jesenice and Olimpija, the team from the country’s capital, Ljubljana—the Slovenian equivalent of Bruins-Habs.

Mateja Kopitar drove her sons everywhere—shuttling them to and from individual games and practices as they always played on separate teams. She saw more hockey than her husband at that time. When Matjaz’s team played at home, he’d bring his sons to the rink. Anze would sit in his father’s stall, too shy to talk, and look around the room. This was it, he thought. One day he’d make it big—he’d make it here.

Kopitar couldn’t see how far this dream could go, then. He couldn’t even watch NHL games, let alone imagine himself playing for the same team Wayne Gretzky once did. The Great One’s poster hung in the middle of the bedroom he shared with his brother, which was scattered with the plastic and wooden mini-sticks they played with nightly until well past bedtime.

When the brothers were still in minor hockey, they picked up the poster just over the border in Austria, in the closest sporting-goods store that sold hockey gear. The brothers saw Gretzky standing tall in his Kings uniform and knew they had to bring it home.

That might have been when his vision expanded beyond the realm of Slovenia, though Kopitar can’t really pin it down. He remembers watching the Russian players who came to his father’s team as imports. The way they played was beautiful, he thought—the puck always moving, every action part of a greater play. But it wasn’t until he watched the Winter Games in Nagano on television that he realized the incredible skill of NHL hockey. Kopitar watched Sergei Fedorov play for Russia and Peter Forsberg for Sweden, and found new models for his game.

Before he was a teenager, Kopitar had outgrown his competition in Slovenia. He played levels above his age and on multiple teams, and he even took a turn in the Slovenian professional league when he was just 15. He’d followed the path of his father right up to his heels; now he’d have to surpass him.

When he was given the chance to play in a Swedish junior league in 2004, Kopitar and his family knew he had to go. He joined the only team that offered him a tryout and set up in a tiny apartment by himself. The move to Sweden was essential, exposing him as one of the top prospects in Europe. He won the league scoring title with 49 points in 30 games, playing in a home rink that sat more than 6,000 people. He was the talk of the 2005 world championship, even when his Slovenian team was being slaughtered by the U.S. and Canada.

Scouts wondered if they’d found Europe’s answer to Sidney Crosby, and pretended they knew where Slovenia was. Unlike most highly touted NHL prospects, though, Kopitar didn’t make the trip to Ottawa for the entry draft in 2005. His team’s pre-season had already started and he didn’t want to abandon his teammates. Instead, the players threw a draft party, watching the names called on television, starting with Crosby. When Kopitar was selected 11th overall by the Los Angeles Kings, his phone rang almost immediately. It was his dad. For years he’d been a hard-nosed, typical hockey man. Now, Matjaz Kopitar wept. It was the first time the son had heard his father cry.

“He couldn’t get any words out,” Kopitar says. They stayed on the phone for a couple of wordless, tear-filled minutes before hanging up. When Kopitar called his father back a little while later, his dad’s pride hadn’t subsided, but the pragmatic coach in him had returned: “This was just the first step you took,” he told his son. “Now it’s time to take the next few.”

up to speed After a relatively slow start to the 2014–15 season with three points in his first 11 games, Kopitar blew up for seven points in

the next five

Kopitar spent the next season playing professional hockey in Sweden before he was thrust into the hyper-critical, make-or-break world of the NHL. More than a nine-hour time-zone shift and nearly 10,000 kilometres separated Kopitar from his family, who stayed up all night to take in his first game, against the Ducks, at 4:30 a.m. in Slovenia. They weren’t able to get a television feed, so they had to settle for a choppy radio call from Anaheim on their computer. “My English wasn’t that good back then, so we didn’t really know what was going on,” says Gasper. But he managed to catch the call of his brother’s name and a “first goal!”—“I think he just scored!” Gasper told his parents. They all crowded around the computer screen waiting for the box score to update, and, sure enough, Anze Kopitar appeared in the goals column when the screen refreshed. “It was pretty sweet,” Gasper says. Anze scored his second before the game was through. When it was over, they all just passed out and waited until the morning to celebrate.

The 4:30 a.m. game time would become a tradition for Kopitar’s parents and grandparents that year as they mastered the art of interrupting a night’s sleep with a couple hours of hockey broadcast from California. Mateja refused to miss any of her son’s games while Kopitar played well as a rookie between fellow freshman Patrick O’Sullivan and Dustin Brown, then in his third year. They were the youngest line on the team, but also the most effective, and new Kings GM Dean Lombardi saw them as the core of his plan to rebuild the franchise.

Kopitar—then just 19 years old—and O’Sullivan, 21, moved into a beachfront condo they rented from teammate George Parros in Hermosa Beach. Neither was a recognizable figure in Los Angeles at the time, so for two young men making considerable wages, Hermosa was paradise. “We were just two kids running around the beach,” Kopitar says. “It was fun.”

O’Sullivan helped Kopitar adapt to a lifestyle that was a long way from his experience in Sweden, let alone Slovenia. He had to learn simple things that others would take for granted, like which restaurants to eat at: The Cheesecake Factory became a favourite. Veterans like Rob Blake, Mattias Norstrom and Craig Conroy were essential, too, taking care of the young Slovenian. On the road, he roomed with Brian Willsie, a journeyman vet who would take him out for dinners and show him around the cities they visited.

On the ice that season, the Kings were terrible—made up mostly of rusted-out veterans—and finished 14th in the Western Conference. But it was a formative time for Kopitar, who finished with 20 goals and 61 points. By season’s end his shyness had dissipated and he became adept at giving back the playful needling he took from teammates.

The following year, his parents and brother moved to Los Angeles, and the four Kopitars settled into a house by the beach. O’Sullivan often found himself at his former roommate’s home. His difficult relationship with his own family had been publicly chronicled during his rise as a top prospect in junior hockey. He felt welcomed at the Kopitars’, filling his stomach with home-cooked meals and admiring the bond Kopitar had with his father. “It was weird to see what a normal family should be like,” O’Sullivan says.

Kopitar’s rise in the NHL since then has been well-documented, though constantly understated. He led the Kings in scoring in his second season and made the Western Conference All-Star team, where he was the youngest player by nearly two years. Under coach Terry Murray, Kopitar developed into one of the best two-way centres in the game, fully utilizing his six-foot-three, 225-lb. frame. He signed a seven-year contract extension for $47.6-million while the pieces of one of the most dominating franchises in the game were starting to come together. Drew Doughty joined the blueline as an 18-year-old in 2008—the same season Jonathan Quick asserted himself as the Kings’ future in goal.

Outside the typical hockey fishbowl, playing games when East Coast fans were getting ready for bed, Kopitar’s remarkable play didn’t register the way you’d expect. But that started to change when Sutter arrived in Los Angeles to take over as head coach in December 2011. The Kings squeaked into the post-season with the eighth seed that year, then ran the table through the playoffs. In the first game of the Stanley Cup final against New Jersey, Kopitar scored an electrifying breakaway goal on Martin Brodeur in overtime, a goal that jolted fans who hadn’t realized just how dynamic he was.

family m-anze Kopitar celebrates the Kings’ 2014 Stanley Cup win with his younger brother, Gasper

When it was his turn to hold the Cup after the Kings won in six games, Kopitar skated to the corner and faced section 105 where his family always sat. He found his mother, father, brother and then-girlfriend, Ines, in the stands and lifted the Cup high over his head. “Not many things bring tears to my eyes, but when he did that it got me choked up,” says Gasper. Later, when the family made their way down to the ice, Kopitar grabbed his brother in a giant bear hug and lifted him up, leaving massive sweat stains on his grey sweater.

Through the lockout-shortened 2011–12 season, Kopitar played with Gasper in Sweden, where the younger brother was trying to carve out a career of his own. Gasper had played junior with the Portland Winterhawks for a brief time and then with the Des Moines Buccaneers of the USHL, before heading back to Europe. Through that time—with two sons playing in completely different spectrums of the game—Mateja was equally passionate about both sons’ pursuits. She’d often set up two screens to watch both Anze and Gasper play if they were on the road, and if she attended a game she’d have the other son’s game streaming on her phone.

At the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Matjaz Kopitar was at the helm of the Slovenian team that featured Anze and became one of the stories of the tournament, beating their rivals from Slovakia and making it to the quarterfinals—a notable accomplishment for a country with less than 200 registered hockey players. Many of the Slovenian players spent their time watching other teams with NHL players practise, amazed by the skill and speed. “It was special to see them looking up to those guys,” says Kopitar. “For me it was special because my dad was there and he was the coach—and you don’t know if you’re ever going to experience the Olympics again, because of the circumstances we have.”

KOPITAR: “To have two Stanley Cups is pretty cool. But maybe I can have another one.”

That part sunk in for Kopitar when he said goodbye to his Slovenian team at the airport in Sochi—before he caught a charter back to Los Angeles. “Everyone thought we were going to get shit-kicked,” he says. “But we held our ground and managed to put Slovenia on the hockey map.”

Returning to the Kings, Kopitar finished the season with 29 goals and 70 points—a team-best total for the seventh straight year. He added 29 points through the playoffs as the Kings pulled through three seven-game series to win the Stanley Cup for the second time in three years.

This time, when he brought the Cup home to Slovenia, Kopitar took more time to enjoy it. Instead of the big public display, he brought it to his grandparents’ house where they sat around the kitchen table sharing its shiny glory, its history, together—as a family. “It’s the best when you can sit at home with your family and the Cup is right in the middle of the table,” Kopitar says. “And you’re just having some drinks, telling stories of growing up.”

Sitting there with their mom and dad and grandparents, Anze and Gasper traced their fingers over the names of the players they adored, which lined the silver rings multiple times: Wayne Gretzky, Sergei Fedorov, Peter Forsberg, Joe Sakic. “And you start thinking, Sakic won two,” he says of a name that everyone knows. “To have two is pretty cool—but maybe I can have another one.” @RobsonDan

Almost Done!

Please confirm the information below before signing up.

{* #socialRegistrationForm_radio_2 *} {* socialRegistration_firstName *} {* socialRegistration_lastName *} {* socialRegistration_emailAddress *} {* socialRegistration_displayName *} By checking this box, I agree to the terms of service and privacy policy of Rogers Media.