I’ve written at length this post-season about the various ways defencemen can put their imprint on the run of play at five-on-five. By keying in on specific sequences through the lens of microstat tracking, whether it be zone exit attempts or zone entries against, we’ve been able to grasp a better understanding of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ individual blueliners do to help tilt the ice.

While it’s necessary to split those two facets into separate quantities in order to isolate different strengths and weaknesses, I’m a big believer that there’s still an inherent interplay between the two. Being able to effectively man the defensive blueline and disrupt the advances of the opposition in a timely fashion should theoretically feed directly into kickstarting the transition offence moving the other way. Or better put: the less time you spend defending, the more time you’ll spend attacking.

There may be no better example of this than Joe Thornton, who drew legitimate Selke Trophy buzz for his play this season despite not generally being considered that type of player. But the reality is he’s stifled most of what the opposition has wanted to do simply because his team has seemingly had possession of the puck whenever he’s been on the ice.

The inverse is true as well. What you typically see from players who make a habit of being hemmed deep in their own zone is that by the time they retrieve the puck, they’re all too happy to dump it out and get off for a change. By devoting all of their energy to defending, they’re not only suppressing any offence they may have generated, but they’re also putting the guys who come on the ice after them at a disadvantage.

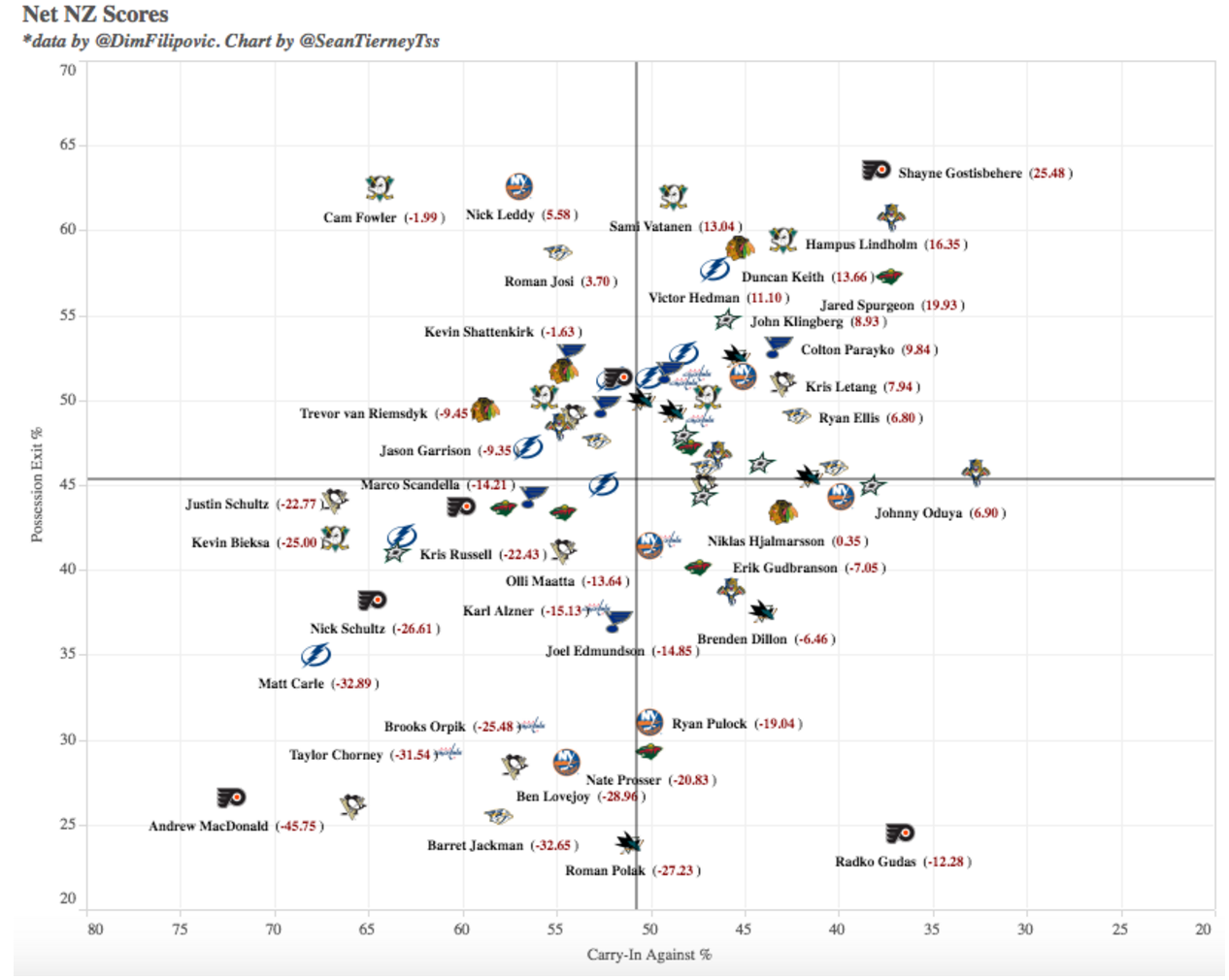

This brings us to the “Net Neutral Zone Scores” charted below, which is based on an aggregate total that combines the two aforementioned components. While it’s a figure that’ll certainly require tinkering and contextual adjustments in the future, for now it can serve as a proxy for identifying how well individual defencemen have controlled their blueline. In the simplest terms: it’s a ballpark estimate for the number of pucks that cleanly move across the blueline and through the neutral zone whenever a specific player is directly involved in the play.

(The numbers are updated all of the way through the Conference Finals, and include only players who appeared in 5+ games this post-season. For a frame of reference: Upper Right Quadrant = Good, Bottom Left Quadrant = Bad.)

The Penguins are an interesting case study here, because despite all of their tremendous team success they don’t really have any standouts here beyond Kris Letang (who himself is just managing to hover above the 50 per cent plateau with his zone exits). I suspect a large amount of that can be attributed to a deliberate system they’re running under Mike Sullivan, with their top-flight forwards being tasked with a larger share of the workload than we typically see. When you have players who can maneuver through the neutral zone like Sidney Crosby, Evgeni Malkin, and Phil Kessel, it’s hard to argue with that preference.

When their defencemen do attempt to make a breakout, they’ve developed quite the affinity for the “alley-oop” play where the puck is lobbed high in the air towards an open sheet of ice for the forward to go and retrieve it. While I’m generally not a huge fan of the play, Pittsburgh’s personnel and the tempo they execute the play with gives them a chance to convert a higher percentage of those plays than your average team. There’s very little hesitation with their decision-making and their north-south movement, which makes it next to impossible for the opposition to set up its defensive shell. The Penguins have proven to be an entirely different animal, and no one has been able to find an answer for neutralizing them.

One final note on the Penguins: I don’t really have an explanation for how good the Schultz and Cole pairing has been since they were put together early in the Eastern Conference Final. Especially after Schultz didn’t even have a regular spot in the lineup early in the post-season, and Cole (along with Ben Lovejoy) was half responsible for one of the least effective pairings you’ll ever see. More power to these two, because they’ve helped the Penguins survive the injury to Trevor Daley.

Fully acknowledging that there’s a certain level of nitpicking involved in finding flaws for a team that was one game away from making it back to a second consecutive Stanley Cup Final, I do think it’s worth calling into question the way the Tampa Bay Lightning have assembled their defence corps.

Despite Victor Hedman’s herculean efforts to cover up many of the holes behind him on the depth chart, the Penguins eventually exposed this group. The common thread between many of these blueliners, who were routinely picked on by Pittsburgh’s speed, is the premium Steve Yzerman and his staff have placed on size. All things being equal, valuing size is perfectly fine. But you get yourself in trouble when you start sacrificing other skills.

By putting so many of their eggs in that one basket, the Lightning were forced to give significant blocks of ice time to players like Braydon Coburn, Jason Garrison, and Andrej Sustr despite the fact they were having a hellish time keeping up with the pace. The end result wasn’t pretty. They were each completing well under half of their exit attempts, surrendering their own blueline to clean carry-ins more than half of the time, and ultimately wound up south of 50 per cent in both shot and expected goal metrics.

If you include Matt Carle in that group, the most troubling thing of all is the Lightning have more than $15 million in cap space tied up in those four defencemen heading into next season. If the Lightning are going to keep pushing for Stanley Cups they’ll need to recalibrate the attributes they’re prioritizing on the back end. If they don’t, they won’t be optimizing their otherwise tremendously talented roster.

On the other end of the spectrum is San Jose’s defence corps, whose balance and well-rounded composition held up exceptionally well through the first three rounds. Brent Burns justifiably garners the lion’s share of the attention because of his gaudy point totals, and the affable character he portrays on and off of the ice. His puck skills are obviously the driving force of his game, but his combination of aggressiveness, reach, and freakishly slick skating ability for a player of his size is underappreciated. These elements cause all sorts of trouble for the other team.

A great example of that unique package is neatly captured in the sequence below, where he single-handedly thwarted a developing man advantage for the opposition and turned it into a scoring chance for his teammate in a matter of seconds:

While Burns is more of an exception than a rule, the rest of San Jose’s top-four defenders still manage to be effective by doing a little bit of everything well in a more subtle manner. Players such as Paul Martin and Justin Braun tend to slip through the cracks because they don’t have one single skill that’s instantly noticeable to the eye in limited viewings, but they make up for that by always being in the right place at the right time. They understand their own capabilities and make smart, (purposefully) simple plays with the puck to keep it moving in the right direction.

Unfortunately for the Sharks, the same can’t be said for all of their defenders. Their third pairing of Brenden Dillon and Roman Polak has been roasted all post-season long by whoever they’ve gone up against, with San Jose controlling just 44.9 per cent of the shots and 32.9 per cent of the goals scored whenever those two are on the ice together.

While Dillon has had his own share of difficulties, it’s really Polak – who currently sits as the league’s least effective defenceman when it comes to transitioning the puck out of his own zone – who has been exposed as a liability. It’s a little bit of a head scratcher that the Sharks, who have put together a very skilled roster, went out of their way to acquire Polak for a premium. They knew what they were getting, and it hasn’t been very good.