Since the 2014-2015 season the NHL salary cap has jumped just $4 million. That’s roughly the same amount as the jump from the 2012-13 to 2013-14 season and less than the jump from 2013-14 to 2014-15. Simply put, the salary cap isn’t moving as quickly as it used to and it’s forcing teams to make difficult sacrifices to avoid overage – just ask the Blackhawks if Brandon Saad could’ve helped their playoff push last season.

With the number of teams pressed against the cap growing the need to shed unappealing contracts becomes greater, and the number of teams that can take those contracts dwindles. As a result you see quality players like Patrick Sharp traded for pennies on the dollar, all in effort to stay within the binds of an ever-restrictive salary cap.

In a league so mired in parity, how do teams gain a competitive advantage? The answer lies in the same system that is so frequently their nemesis.

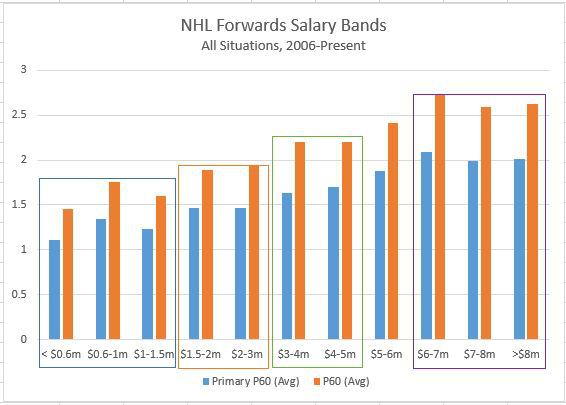

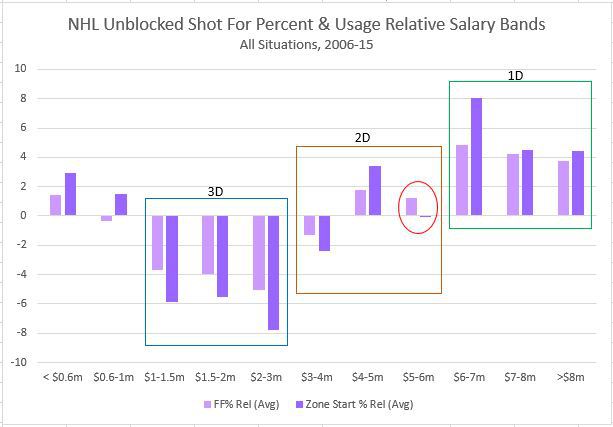

Carolyn Wilke has done excellent work in this field, and if you haven’t seen it, you should definitely take the time to dig deeper into her work. As a result of her efforts we can determine the average value of players based on their salaries, and from that expand on how to maximize the value for each salary band. Each of these images was produce by Carolyn.

Starting with the forwards what we see is pretty standard – the more money you make, the more points you score; the one exception being the $0.6-1M range, but this is skewed due to entry-level contracts (ELC).

When it comes to defencemen things get a little more complex, but it follows mostly the same pattern. This time looking at possession numbers we see typically the higher you’re paid the better you control play, with the one exception being the $5-6M range; this suggests we may be overvaluing some second-pairing defencemen.

Knowing the averages for each category, the question then becomes how can teams maximize production for each salary band; in other words how can you get better production at a lower cost?

In a sentence, NHL general managers need to take more risks.

Think of the recent Stanley Cup winners. Most of those teams have had something in common: strong players on entry-level contracts. When the Penguins won the cup in 2009 Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin were both on ELCs. When the Blackhawks kicked off their string of Cups they started it with Patrick Kane and Jonathan Toews both on ELCs, and this year the Penguins were backstopped by a goalie who had never previously touched NHL ice – also on his ELC.

The problem general managers face is that most players don’t make the NHL in the first year of their ELC; they usually take a season or two to adjust to the NHL from junior or the AHL. Some of this can be circumvented by using the ELC’s sliding scale, which allows prospects to play up to nine NHL games without counting towards the first year of their contract, but only offers the GM a brief glimpse into the players potential.

The other option is to keep them up longer, and sacrifice the first year of their contract. That leaves GMs with just a season or two of work to judge a prospect and decide how much they are worth to the team, and how long to sign them. It’s not a lot to go on.

Enter the bridge deal – a two or three year contract that says, “I like what I’ve seen so far, now show me you can keep it up.” It’s the perfect proposal to a young prospect. It keeps them on the team, doesn’t chew up too much of their prime, and keeps costs down for the GM over the next few seasons. Issues only begin to arise once these contracts come to an end. Now you’re left with a very capable player, in the middle of his prime, asking for a lot of money. Often, more than the team can afford.

This issue is only exacerbated when it comes to small market teams who can’t afford to spend to the salary cap – the Anaheim Ducks and Bobby Ryan being a perfect example of this.

This raises the question, how do teams that can’t afford to spend to the cap compete when they can’t retain their best players?

The answer is simple: by eliminating the bridge contract.

A quick look around some of the best contracts in the league brings up a number of names, but the most prominent is Erik Karlsson. The two-time Norris Trophy winner signed a seven-year, $6.5-million contract immediately after his ELC. In comparison, after P.K. Subban‘s two-year $5.75 million bridge deal, he signed an eight-year deal with a $9 million AAV – making Karlsson look like an even bigger bargain.

This off-season has already been a prime example as more teams stray from the bridge deal. The Colorado Avalanche inked 20-year-old Nathan MacKinnon to a seven-year $6.3-million contract that already has captured the hearts of Avs fans. Not to be outdone, Winnipeg Jets GM Kevin Cheveldayoff locked Mark Scheifele down for the next eight years to the tune of $6.125 million.

The Hurricanes and Panthers have also done the same signing Victor Rask and Vincent Trocheck to long-term deals.

Although the initial cost of these contracts may seem high in comparison to their bodies of work, the contracts are signed on a mentality opposite to the typical NHL contract. Instead of paying a player for what they’ve done, teams are paying players for what they’re going to do.

It’s a situation that offers positives for all parties involved. From a players’ perspective it’s job security; a promise that the team is willing to commit to them for the foreseeable future. For the team it’s a contract that, if your evaluation of the player pans out, will be well below market value when they enter their prime – especially as the cap continues to rise.

Eliminating the bridge deal takes the benefits of the ELC and extends it, offering teams the cap-room to sign big name free agents come the deadline. It’s the reason the Avalanche can afford to have MacKinnon and Gabriel Landeskog for a combined $11.625 million cap-hit next season, and the reason they may not be able to bring back Tyson Barrie after signing him to a two-year $5.2 million dollar deal in 2014.

For small-market teams the best way to stay competitive is to maximize contract value, or as Eugene Melnyk would put it, the cost-per-point. The best way to do that is to stop playing it safe.

It’s time for NHL GMs to take the risk and bid adieu to the bridge contract.