One of the most important aspects of playing goal is the mental preparation that it requires. If you have never played the position, it is difficult to understand or relate to a goaltender while watching him in a game. There are plenty of mental hurdles to overcome from recovering from bad goals to staying in the right headspace despite a light workload.

Kelly Hrudey mentioned that when he played, he broke the game into five-minute segments and focused on delivering a shutout during that time span because it allowed him to create an attainable goal that would shelter him from mental breakdowns should he fail. If he allowed a goal, he would set a new five-minute window.

Maintaining focus is extremely important. As Kristers Gudlevskis was getting bombarded during the Canada-Latvia game at the Olympics, Carey Price had to stay mentally ready in order to avoid a letdown that could cost his country a gold medal. The pressure on every shot he faced was enormous.

When he delivered the expected gold medal it was easy to overlook what he accomplished because he faced just 20 shots per game—but what if 20 shots per game isn’t easy?

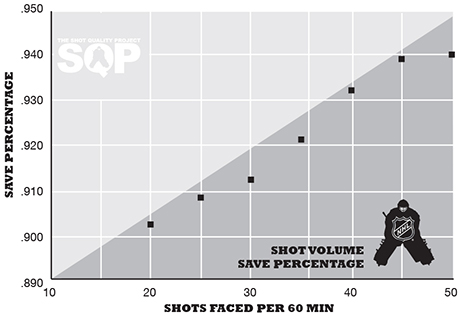

This season, Twitter started spitting out facts about goaltenders’ records when faced with absurd workloads. Jonathan Bernier is 6-3 with a .950 save percentage when facing 40-plus shots. Amazing right? Maybe not. This season, goalies have been exposed to 40-plus shots 159 times. Their average save percentage on those nights is .940. Only 30 of those 159 games resulted in a goaltender registering less than the 2013–14 NHL average of .913. Ninety-eight of those starts resulted in .930 or better. I decided to see if there was any type of link to shots faced and save percentage.

I researched all starts of 50 minutes or more to remove any sub 20-shot starts that were filled with noise from terrible performance and early removal. I then categorized games into categories based on shots faced.

< 20 shots

21–30 shots

31–40 shots

40+ shots

Data based on the 2013–14 season

I found that as a goaltender’s workload increased, so did his save percentage. But the results are counterintuitive—we generally fawn over goaltenders with the high save count with first-star recognition. When reviewing the 156 games with 20 shots or fewer, goaltenders registered a sub-.913 save percentage 92 times. When facing fewer than 20 shots, it is essential to not allow more than one goal to maintain anything above .900.

Henrik Lundqvist has faced fewer than 20 shots 20 times during the past four seasons, and he has allowed one goal or less six times—his save percentage in those 20 starts is .885. “The King” has 12 starts of 40-plus shots during the same time span and has given up one or less five times, totaling a save percentage of .956. Research each individual goaltender and the same results consistently arise.

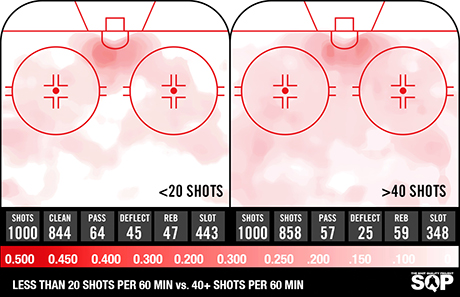

I wanted to see if my x,y data could provide any answers. I separated 30,000 shots’ worth of my data into individual game events like I did above. I wanted to see the effect on the extreme comparable so I mapped games with fewer than 20 shots versus games with more than 40 shots.

Visually we can see where a lot of the extra shots originate from.

The slot volume on the smaller workload is higher. The home plate area is the definition for most scoring-chance projects, so the lighter workload exposes goalies to a higher percentage of scoring chances. Without the save-percentage inflators provided by shots from above the faceoff circles (which have an expected save percentage of .974) it becomes difficult to register anything over .900 when facing lighter than a 20-shot workload.

The pre-shot movement isn’t that decisive, although the smaller workload does see slightly more difficult opportunities. When I calculated movement, second-chance opportunities, deflections and distance against the expected league averages, the lighter workload represented only a .018 difference, half of the .036 represented in the actual numbers.

The SQP data can’t quite bridge that .018 gap to provide a definitive answer for why a larger workload produces higher save percentages, but there may be other noise to explain it. Maybe the assumption that more work produces sharper focus is 100-percent true. Goaltenders must play mind games with themselves to concentration when faced with lulls in play, but even somebody as mentally strong as Lundqvist can’t seem to excel when given an extremely light workload. When faced with constant work, their focus is easily directed to the action going on in front of them.

Score effects could play into the inflated shot totals as well. Teams that trail tend to put more pucks on net.

We won’t likely have a definitive answer for this until SportsVu cameras populate every NHL arena. Until then if you see a goaltender drop a .940 save percentage during a 40-plus shot game, keep in mind that statistically the performance is average, almost expected, not the work of a phenom.