One of the toughest things in sports is dealing with is an aging superstar. The player generally sees himself as an extension of the impact player he’s been his whole life—a conqueror of every challenge they have faced since childhood. They have had success after success and struggle to understand or accept that they can no longer match their personal expectations.

It’s also a struggle For management and fans. Both want to show loyalty to the player who provided them with championships and memories, but they also want to maintain success on the ice.

This is the scenario currently playing out in New Jersey. Martin Brodeur’s resumé is pretty impeccable and he has a sterling reputation throughout the NHL—one so strong that he is being considered a trade candidate because his Stanley Cup experience could possibly push a contender to champion.

The problem is that over the past four seasons Brodeur has struggled to produce back-up level goaltending, let alone championship-calibre performances. The Devils addressed this issue when they acquired Cory Schneider last summer, but Brodeur’s legacy and iconic status have forced New Jersey into platooning the two, even though one is producing at an All-Star level and the other would be in the American Hockey League if not for his CV.

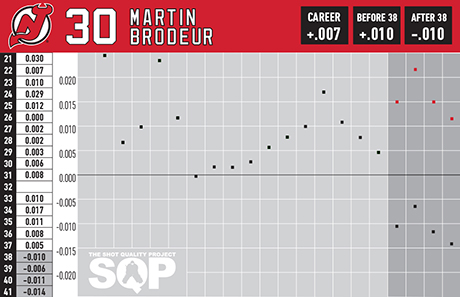

Over the past four seasons, Brodeur has crashed to a level on par with a career backup like Peter Budaj. Comparing Brodeur’s seasons to Cory Schneider’s (in red) and against the league average shows there is no question who the better goaltender is today.

If we look at both of their records, we might not see where Brodeur is costing the Devils a wild-card spot. New Jersey is three points out of the eighth and final playoff spot. In Brodeur’s starts, the Devils have earned 32 of a possible 58 points, good for a 90-point pace. Schneider’s have only produced a .500 pace, or an 82-point pace. So on the surface it appears Broduer is the reason the Devils are still in the hunt. Not so much.

At issue is goal support. Even though Brodeur has puttered along with a .900 save percentage, the Devils are averaging three goals a game in support. Schneider is receiving fewer than two goals for per game. To illustrate this I took the shots against and subtracted them from goals for. That tells us what save percentage a goaltender must register to earn a point based on their team’s offensive performance in front of them.

In a 3-1 victory, the assumption would be that to earn a point the goaltender would have to allow no more than three goals. Inversely, in a 3-1 loss the goaltender would need to have allowed no more than one goal.

Schneider has had to be well above league average just to record a .500 record. Brodeur, on the other hand, to register .500 would essentially have had to play like Glenn Healy all season. When putting both goaltenders to the shot quality test the same conclusion is met.

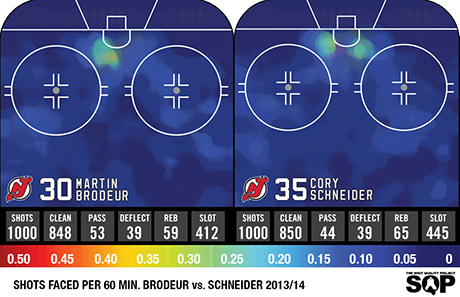

Both Brodeur and Schneider are facing close to an average workload. Brodeur is facing slightly more transition passes, while Schneider is exposed more to rebound and slot opportunities. Even visually we can see that neither goaltender is really being overly exposed in one area. With things being fairly equal we should expect two evenly matched goaltenders to produce comparable results.

The problem is that Schneider is markedly superior to Brodeur. If the Devils had handed Schneider the starting role and spot-started Brodeur—like a regular backup—they would likely have bridged the three-point gap and sit in playoff position.

Ultimately this observation isn’t solely based on data. Martin Brodeur is the last of his kind. A goaltender who lacks zero on ice mobility. The next butterfly push he does will be his first. He gets up with the improper drive leg, he lunges at pucks, he cheats and guesses and relies on old-school techniques like shading blocker side to entice shooters to shoot glove side. He is of a different generation. He was not taught modern techniques and after the success he has enjoyed at the NHL level, probably saw no reason to learn any.

The problem is that as goalies age and their reflexes dull and they don’t rely on precise positioning and strong recovery position, they are prone to fall off a Curtis Joseph-like cliff. This was exposed in the data when differentiating Brodeur’s and Schneider’s success.

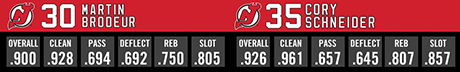

The number that explodes off the page is clean save percentage. During my study the league average is .951. The number is significant because it has the highest sample and 85 percent of the shots the Devils have faced in 2013-14 have been clean. The difference between .694 and .657 lateral save percentage on 50 shots is two to three goals, but the difference between .928 and .961 on 850 clean shots is 28 goals. The difference between Brodeur and Schneider comes down to the ability to stop shots they can see. Schneider is elite, Brodeur is below replacement level.

The logic that an aging goaltender who relies on 20-year-old techniques cannot stop pucks he can see is consistent with the data. Brodeur just isn’t a starter in the NHL any longer. The Devils must know this, but must be struggling with the loyalty issue described above. However, any team that takes a chance with a goaltender who would not be in the league were in not for the hyperbole surrounding his name and past accomplishments deserves to lose.

It is a tough situation for the Devils, but they need to move forward with Schneider.