It seems that at least once per summer, a contract negotiation between an emerging young star and his NHL teams goes all pear-shaped. This year, the distinction belongs to Columbus Blue Jackets pivot Ryan Johansen, the 2010 fourth-overall pick who broke through in 2013-14 after two disappointing professional seasons.

In hindsight, the impasse seems predictable, simply because of the dichotomy between what Johansen accomplished last season and what he had done previously as a pro. It’s well worth remembering that as recently as May 2013 the centre was a healthy scratch—and not for the Jackets, but for their AHL affiliate, a team fighting for its playoff life. “It’s not something I enjoyed doing or wanted to do,” Springfield Falcons coach Brad Larsen told the Columbus Dispatch at the time. “But, to be honest with you, it wasn’t all that hard of a decision. We talked after Game 2, and I tried to ramp him up. In Game 3, we just felt like he wasn’t all there, like he wasn’t invested 100 percent.”

For a limited time get Sportsnet Magazine’s digital edition free for 60 days. Visit Appstore/RogersMagazines to see what you’re missing out on.

With that kind of history, it is entirely understandable that the Blue Jackets would look at Johansen’s 2013-14 performance with some skepticism, asking themselves if it’s really representative of that player’s future performance. Johansen’s camp understandably wants the player to get paid for what was an exceptional year. He led the team’s forward group in minutes played and was second only to Brandon Dubinsky (who regularly kills penalties) in minutes per game. He also scored 33 goals; one more would have had him in the NHL’s top 10.

The Blue Jackets’ solution to the conundrum has been the obvious one: to offer the player a “bridge” contract, a short-term deal to allow both sides to feel each other out. It hasn’t been received well; Johansen called it a “slap in the face” back in June and the Dispatch’s Michael Arace writes that Johansen’s agent is seeking something in the neighborhood of $7.0 million per season on such a deal.

Adding fuel to the fire are the options available to each side. The Jackets are well-stocked down the middle, and while they obviously want Johansen playing they could go into 2014-15 reasonably comfortable with Dubinsky, Artem Anisimov, Boone Jenner and Mark Letestu at centre. Johansen’s side can hope for an offer sheet; a rival team could bid well over $6.0 million for his services without surrendering more than a first-, second- and third-round draft pick.

The art of the negotiation here is fascinating. The principle question at its heart, however, is whether or not Johansen’s 2013-14 is an aberration or truly represents him coming of age as a No. 1 centre in the world’s toughest league. It’s a question that warrants further examination.

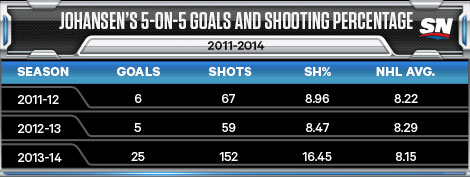

A common warning sign of unsustainable success is shooting percentage. If we see a big spike in a player’s personal success rate, it gives rise to suspicions that he just had one of those years where pucks go in; likewise if we see a big spike in the shooting percentage for an entire team with a given player on the ice.

Most of Johansen’s goals (25 of 32) came during five-on-five play, and there is indeed a red flag in the data:

Over the first two seasons of Johansen’s career, he was just slightly better than the NHL average at converting shots into goals. In 2013-14, his shooting percentage basically doubled. It’s unlikely that this was a result of an increase in skill on Johansen’s part, since we typically see NHL players’ shooting percentage fall off with age.

What is possible is that Johansen’s first two seasons understate his true shooting ability. This is a player who was a fourth-overall pick, who only had a small sample of 126 shots in five-on-five NHL play on his resume, who shot at a 17.9 percent clip in the minors over 40 games in 2012-13. On the other side of the ledger, this is also a player who was always more playmaker than goal-scorer and who only notched 25 goals in his draft year. Moving beyond the personal, the fact remains too that only a very, very small number of players are consistently able to out-shoot the NHL average by anything even remotely resembling a 2:1 margin. An additional wrinkle is that three of Johansen’s goals were into empty nets; only three other players had more.

Other indicators point to a player who does a lot of things right. Johansen can’t be accused of profiting from the efforts of superior linemates; he spent most of 2013-14 playing with Nick Foligno (who has never scored 20 goals or recorded 50 points) and the since-discarded R.J. Umberger. He played tough minutes, ranking near the team lead in both quality of competition and the percentage of his shifts starting in the defensive zone. Even with those limitations, his team did an exceptional job of out-shooting the opposition when he was on the ice.

Despite his somewhat checkered history, 2013-14 reveals that Johansen likely is an exceptional player, a big strong centre who drives out-shooting and consequently out-scoring in exactly the manner that was envisioned when the Jackets picked him so early at the 2010 draft. Having just turned 22, he likely isn’t finished improving either. There is, however, a good chance that last season’s goal outburst is a bit of an aberration and that his offensive totals may regress somewhat.

Understandably, Johansen and his agent hope to cash-in on a season in which the player was very good but also had a lot of things go right. Just as understandably, the Blue Jackets would rather take a wait-and-see approach. The trick now is to find a contract that balances the risk for both parties while simultaneously rewarding Johansen for the season he just had.

That’s not easy to find, even between parties with a good relationship and positive history. It’s going to be even more difficult for two adversarial camps, each with a potential nuclear option at its disposal. The obvious solution is for Columbus to offer a little more term than it is really comfortable with and for Johansen to accept a more modest dollar figure. That compromise doesn’t seem imminent.