One player is the centre of the Pittsburgh Penguins’ most productive line through three rounds of the playoffs. The other was the No. 2 defenceman for the Tampa Bay Lightning for almost as long in the absence of injured rearguard Anton Stralman.

The connecting link between Nick Bonino and Jason Garrison is that both were acquired by their current clubs via trade with the Vancouver Canucks.

The deal for Garrison took place at the 2014 NHL Draft and was part of a larger series of trades on the draft floor. It was a defensible move in the larger context, which also saw Vancouver add Luca Sbisa in a separate deal. Sbisa was younger, cost less than half as much as Garrison at the time, was a reasonable replacement for the outgoing veteran on the penalty kill and at even strength. With the Canucks having other options on the power play, swapping Garrison for a second-round pick made some sense.

The trouble is that after a single season, Sbisa stopped being cheap. He signed a three-year deal with a cap hit just $1 million shy of Garrison’s contract, and given his more limited skillset it’s difficult to call that a savings. That contract decision undid whatever rationale the Canucks had to trade Garrison.

Meanwhile, the Lightning benefited. After Victor Hedman, most of Tampa Bay’s key building blocks on the blue line are veterans acquired rather than young players developed within the organization. Stralman was added via free agency, while Garrison and Braydon Coburn were procured via trade.

The Lightning have not yet had cause to regret dealing that second-rounder for Garrison. In 2015, Garrison was the team’s No. 3 defenceman as it advanced to the Stanley Cup Final. This spring, with Stralman hurt, he filled the No. 2 slot for most of his team’s deep playoff run.

Garrison hasn’t been a perfect fit in the role, and his possession numbers both years in Tampa have been below club average, but he has been useful as a jack-of-all-trades player.

My colleague Dimitri Filipovic’s findings this spring show that nicely: Although not outstanding in either area, Garrison has been about league-average both in getting the puck out of his own end of the ice and in defending the Tampa Bay blue line from opposition rushes.

But if the Garrison deal was a defensible move for the Canucks, there never was such an excuse for the trade that sent Nick Bonino to Pittsburgh. Vancouver paid dearly in assets, salary and downgraded at the centre position.

Vancouver acquired Brandon Sutter and a third-round pick from the Penguins in exchange for Bonino, Adam Clendening and a second-round pick. Sutter was in the final year of a $3.3 million deal and quickly signed a multi-year extension worth just under $4.4 million, while Bonino had two seasons left at a $1.9 million cap hit.

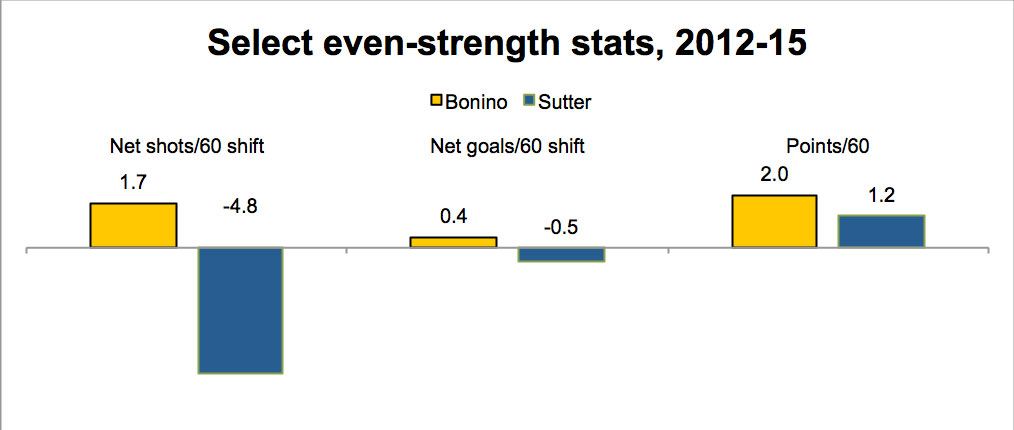

The sweeteners provided by the Canucks and the nearly $4 million in additional salary taken on over two years look bad, but the primary reason this deal was so lopsidedly in favour of the Penguins is that while Sutter is a more famous player, Bonino is the better one. Consider how both player affected his team’s even-strength numbers in the three years prior to the trade:

When Bonino was on the ice in Anaheim and Vancouver, his team got better. They fired two more shots per hour, and scored nearly half a goal more. His scoring rate of 2.0 points/hour ranked 71st among NHL forwards (min. 1,000 minutes) over that span; in those three years he was as likely to pick up a point on an even-strength shift as Henrik Sedin or Bryan Little, both first-line centres.

On the other hand, when Sutter was on the ice in Pittsburgh, his team got worse. Its shot differential fell by five shots per hour; its goal differential fell by half a goal per hour. Sutter’s personal scoring rate of 1.2 points/hour was tied with depth players like Michal Handzus and James Sheppard.

The rationale for the move was that Sutter played in a defensive role behind superstar pivots, while Bonino played in a sheltered role behind lesser lights. But that never made much sense. In terms of quality of competition, Sutter and Bonino’s numbers were virtually identical (as one would expect, Sidney Crosby and Ryan Getzlaf drew the toughest opponents); ditto in terms of defensive zone assignments.

The difference between the two has been painfully clear this season.

In Pittsburgh, Bonino has kept doing what he’s always done. His team improves by three shots per hour when he’s on the ice, and by 0.3 goals per hour; totals virtually identical to what he’d attained in three previous seasons. He’s certainly benefited from playing with Phil Kessel, but even in his minutes away from Kessel his scoring compares favourably to Sutter.

Meanwhile, in Vancouver, Sutter was hurt for much of the year so it’s been difficult to judge. Prior to injury, though, he was doing what we’ve come to expect. An anticipated offensive evolution never came; after putting up 33 points in 80 games a year ago Sutter was on pace for 36 over the same span this season. Worse, the Canucks’ shot metrics as a team dipped when he was on the ice and his possession woes were not cured with increased responsibility.

The bottom line is that both Eastern Conference finalists owe a measure of their success to Vancouver. Tampa Bay added a defenceman in a reasonable trade in which the Canucks failed to capitalize on the cap savings attained. Pittsburgh, on the other hand, simply picked up the better player in a one-for-one swap and then managed to convince the Canucks to give up futures and cap space, too.