James Hinchcliffe almost bled out at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Now, he’s ready to return to the track.

By Dan Robson in Indianapolis

Photography by Aaron Wynia

Rocketing around the oval track at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, everything was going right for James Hinchcliffe. He had recently signed a new contract with Schmidt Peterson Motorsports for his fifth season on the IndyCar circuit and his team had won the second race of the year in New Orleans a month earlier. As he accelerated into the third lap of a practice run, preparing to race in the Indy 500, Hinchcliffe was locked into the tiniest details that might give him an edge in the coming race (during which he’d cover roughly the distance from his hometown in Oakville, Ont., to Indianapolis). Travelling at more than 320 km/h, Hinchcliffe’s red gloves gripped the wheel as he gained on Juan Pablo Montoya, also on a practice run. He tucked his car up behind Montoya’s bumper, using his rival for a tow lap. That’s the last thing Hinchcliffe remembers of the day. A blink, and there was nothing.

Hinchcliffe can’t recall the jolt he received when a small piece of his suspension snapped as he entered the oval track’s third turn. He can’t recall his front right wheel rising off the asphalt, or hurtling toward the wall, unable to steer. Despite the speed, Hinchcliffe knows that it would have felt like forever as he slid toward the inevitable collision. He knows that at some point in those frozen flashes of time, he would’ve accepted that all he could do was let go of the wheel and wait. He was conscious through the rest of it, but his mind is gracious with the blanks it provides. He doesn’t remember the impact, or the flying debris, or the fire, or the pain. He doesn’t remember spinning to a stop with the right side of his car smashed to pieces. He has no memory of the realization that a severed metal rod from the car’s suspension had ripped through his seat, torn into the back of his upper right thigh, ripped through his pelvis, exited just below his left hip and embedded itself into the side of the cockpit.

James Hinchcliffe had experienced several near misses on the track before. Like every driver who climbs into a race car and pushes against the limits, he understood the risk he faced with every lap. But the gregarious “Mayor of Hinchtown” had never endured the kind of trauma he did that day last May at the Brickyard. He was spared by only fractions of an inch, and saved by an emergency crew that wasted not a fraction of a second. Lucky just to be breathing, Hinchcliffe, 29, has embarked on a relentless effort to return to the track in time for the 2016 season. In March, he aims to climb into his car and race in the Firestone Grand Prix of St. Petersburg in Florida, completing his remarkable, once-unthinkable comeback. This is the story of that journey.

Track surgeon Tim Pohlman was dozing in a chair at the Speedway’s field hospital when a peanut butter–stuffed pretzel struck him between the eyes. “Wake up, doofus!” shouted Dave Clark, the head of the field hospital. “We’ve got work to do.”

It had been another sleepy day during practice runs at the Indy until the tattered wreck of Hinchcliffe’s gold car spun to a halt on the closed-circuit TV in the hospital office. Startled awake, Pohlman looked up at the screen and immediately knew it was bad. Normally, a driver puts his hands up to indicate he’s OK. But the only movement came from Hinchcliffe’s helmet, which bobbed back and forth. The Holmatro safety crew—IndyCar’s emergency response team of paramedics, doctors and firefighters—arrived within seconds of the crash. One of the first held five fingers up: Code 5, meaning the driver’s life was in peril. But it was taking too long to get Hinchcliffe out of the car.

On the track, IndyCar’s director of safety Mike Yates tried to slide his hand into the cockpit beside Hinchcliffe, but there was no room between the driver and the walls of the tub. Hinchcliffe told them his seat belt was stuck and he couldn’t move. He said he felt pain in his lower back. Yates had dealt with many difficult scenes in his long career as a track paramedic, so when the jaws of life finally opened up enough of a gap for him to reach in, he knew the situation was desperate. The bright-red blood pooling in the tub meant an artery had been severed. But Yates couldn’t see the wound and didn’t immediately see the rod, which had entered the seat beneath Hinchcliffe and torn through his side, spiking him in place. On its path through his body, the rod had struck Hinchcliffe’s superior gluteal artery, but that was relatively fortunate—had it instead severed his common iliac artery, which provides blood to the lower body, he would have bled out in under two minutes. At the scene, Yates’s first priority was to get the driver out of the car. So he and four other members of the safety team carefully but urgently pulled Hinchcliffe up and out the left side of the car and put him into the ambulance. The rod slipped back out through Hinchcliffe, but Yates wouldn’t realize that until he was shown photos from the scene later.

Yates and Andrew Stevens, a trackside doctor, climbed into the ambulance behind Hinchcliffe, raced to pick up Pohlman at the field hospital and took off down West 16th Street toward Indianapolis University Health Methodist Hospital. Hinchcliffe, stripped to his fire-retardant base layer, faded in and out of consciousness as the paramedics hooked up an IV to pump a saline solution into his system, helping to buy a few precious minutes. Pohlman tried to dam the gaping wound in Hinchcliffe’s side, reaching in to apply as much gauze as he could. Yates did the same to the wound on his other side. It was of little use. The severed artery was deep in Hinchcliffe’s pelvis, and there was no way to control the bleeding without surgery.

About 20 minutes after the accident, Hinchcliffe was rushed into the shock room at Methodist, where a trauma crew immediately started pumping bags of O-negative blood into him. Unconscious and on life support, he was rolled onto his side, and Pohlman found a pool of blood soaking through the gurney. He realized the spike had ripped through both of Hinchcliffe’s glute muscles, leaving two more wounds that were still bleeding. The blood was rushing out of him as quickly as they pumped it in. There was no more time. The hospital trauma team ran down the hallway, wheeling the gurney toward an elevator to the operating room. On the brief ride up to the floor above, Pohlman searched for Hinchcliffe’s pulse. He couldn’t find it. The doors opened into the operating room, but the surgeon knew that survival was improbable. A gut-wrenching thought flashed through his mind: James Hinchcliffe wasn’t going make it.

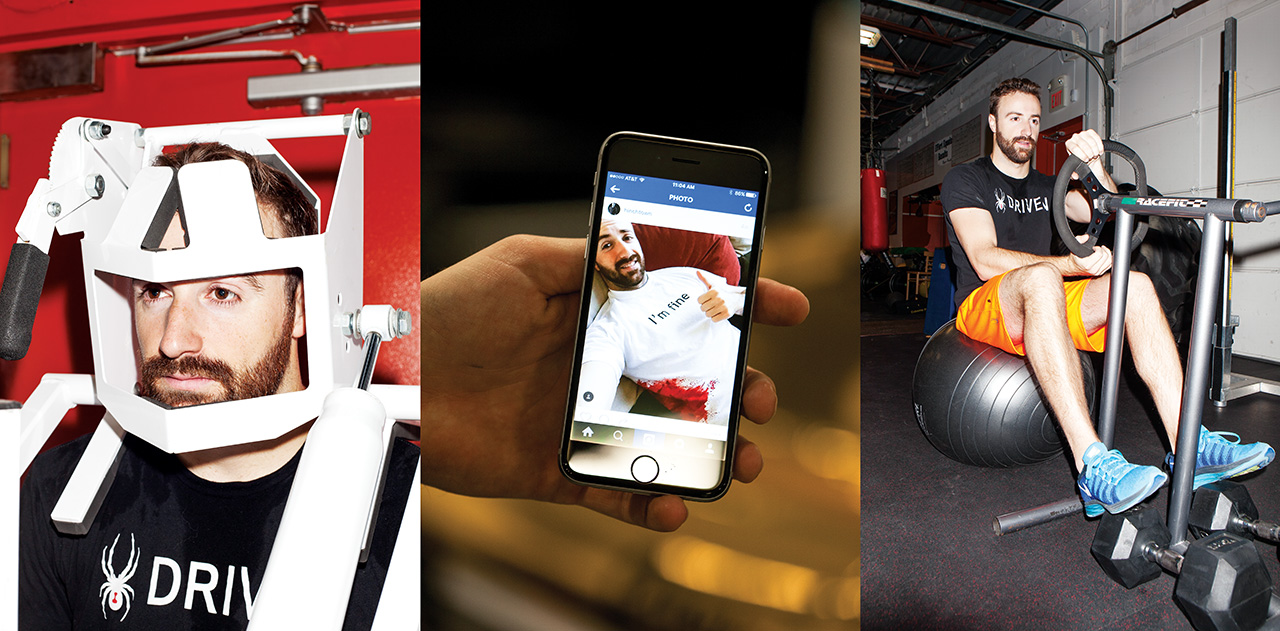

trial by injury In addition to the damage done to his legs, hips, buttocks and abdomen, Hinchcliffe had a severely strained neck that limited movement months into his recovery

A blink and there was something. Bright lights. White walls. A tube in his throat. Beeping machines. A blink, and then a hospital bed. Everything else was hazy. No sense of time or place. But the deep-seated memories, the ones that make a life, were still intact. The posters of cars plastered on the wall of his childhood bedroom. The monthly arrival of his Jacques Villeneuve fan-club letter. Sunday mornings watching races with Dad. Steering bumper cars while dad worked the pedals. Skipping down the Toronto Indy bleachers to see the cars rip by. Waiting three hours in the heat for a chance to meet his idol, Greg Moore. The ham-and-cheese sandwiches his mom made before every go-kart race. The same Spencer Davis Group song, “Gimme Some Lovin’”—a superstitious routine—blasting from the stereo as the family drove to the Goodwood go-kart track just north of Toronto.

Hours earlier, his pulse had been undetectable, but ever so weakly, his heart beat on. The surgical team had cut into Hinchcliffe’s abdomen, inserted catheters, reached the artery deep in his pelvis and finally closed it off. The Holmatro crew’s swift work had given him a chance, and Pohlman’s expertise had pulled him along, but Hinchcliffe had endured trauma that should have killed him. An hour and 20 minutes after the crash, Hinchcliffe was alive. Most people, Pohlman says, would have died before reaching the operating table. “He saved himself, really,” Pohlman says, crediting Hinchcliffe’s fitness for the few extra minutes that spared him.

Several hours later, awake in the ICU, Hinchcliffe slowly pieced together what had happened—and decided that he was the “luckiest unlucky bastard in the world.” Aside from slipping past the artery that would have killed him right on the track, the rod narrowly missed a series of nerves at the base of his spine that, if damaged, would have affected the function of his legs. (Instead, it merely chipped his tailbone.) In the end, 22 units of blood were pumped into him—twice the amount his body initially held.

Unable to talk, Hinchcliffe was given a pad of paper to communicate with his girlfriend, Kirsten Dee, and his close friend and fellow IndyCar driver, Marco Andretti. He asked how Dee was feeling in the wake of the trauma and whether his parents knew he’d survived. Then he scribbled one more question: “When can I get back in the car?”

Hinchcliffe was told he wouldn’t walk for two weeks and that he’d be in the hospital for at least a month. He walked four days after the accident and left the hospital in 10. He’d lost more than 20 lb. from his already lean frame, dipping as low as 144 lb. on the scale. Partially to avoid his gaunt reflection, he grew out his beard and vowed that he wouldn’t shave it until he got back in a race car. Members of the Schmidt Peterson crew were shaken by the near death of their driver, who had quickly endeared himself in his first season with them. They proudly wore “Hinch Strong” hats and T-shirts. Thousands of fans signed an enormous “#GetWellSoonHinch” banner at the Brickyard, and the same hashtag was written in big white letters down the pole at the start of the Indy 500 a few days after the accident. Less than a month after the crash, Hinchcliffe served as the grand marshal at the Honda Indy Toronto, maintaining a perfect attendance record that started when he was 18 months old. Pale and thin, he cheerfully signed autographs and posed for pictures. The trip home for the race was a statement to the fans and to his team, but most importantly to himself: You can be damn sure that James Hinchcliffe will be back.

On June 18, exactly a month after the accident, he sat on a weightlifting bench at PitFit Training in Indianapolis. He was hoping to continue to speed his way through the recovery process when his long-time trainer Jim Leo handed him a pair of 2.5-lb. weights to do some side-arm raises. “What are you? High?” Hinchcliffe said, scoffing at the tiny load. But he was gasping after 10 reps.

Frustrated by how little strength and endurance he had, Hinchcliffe’s instinct was to push harder in the gym, even though his wounds were still healing. He had an incision in his stomach from the surgery and had to let his muscles heal before he could engage them. He also had a severely strained neck and had to be seated with his back braced for support during any exercise. (He was given a pillow shaped like a giant doughnut with pink icing and sprinkles to sit on at home.) For the first time in his life, Hinchcliffe had to take it slow.

Leo, who has worked with Hinchcliffe since the driver was 17 years old, designed a program that would slowly rebuild his cardio and muscle mass, while eventually working in exercises that would sharpen his reflexes. Hinchcliffe started off on an Airdyne bike, slowly pumping its handles back and forth to spin a giant fan in front of him. When his doctors cleared him, he moved to the treadmill. Leo had him walk at a pace of 2.5 km/h.

During the next few weeks, Hinchcliffe started to make progress. Then one day he jumped on a slackline in the gym before Leo could object to the core-straining exercise. But Hinchcliffe managed to teeter his way across it. He could feel the things he’d lost—balance, strength, endurance—starting to come back. He posted updates of his progress on Instagram. Just under a month after he returned to the gym, he posted a pedometer reading that showed he had taken nearly 10,000 steps in one day next to another one from the early days after the accident, when he’d taken just five. “Baby steps, but we are getting there,” he wrote.

But his stubborn drive set him back, too. A stomach flu hit him in July, and he tried to sweat it out. When it lasted for more than a week, Hinchcliffe finally had to admit something was wrong. He wound up back in the hospital with doctors concerned he might have contracted C. difficile, a serious bacterial infection that can be fatal. Hinchcliffe again found himself in a bed having fluids pumped into his system. After two days hooked up to an IV, the flu started to lift and tests returned negative for C. difficile. A fortunate break, but in the nearly two weeks it took to get through the bug, Hinchcliffe lost all the weight he’d gained back. Most of his strength was gone, too. He was put on a special diet: Eat whatever you want, and lots of it. That small bonus aside, Hinchcliffe was sent back to the start of his recovery. “We had built up to certain points, but there was so much further to go,” says Leo.

Through August, Hinchcliffe still wasn’t able to put any strain on his neck. Once, while looking down, he was thrust into so much pain that it took him nearly 10 minutes to be able to raise his head again. But still, he insists that the psychological struggles were worse, and most were rooted in his inability to immediately get back on the track. He worried that despite his relentless efforts, the physical effects of the accident might never fully heal, leading to an early end to his racing career. With no memory of the accident itself, Hinchcliffe still seemed detached from the grim reality of it, even though Pohlman had walked him frame-by-frame through that frantic day. Hinchcliffe knew the details, but he couldn’t see or feel them—it wasn’t quite real—until a tragedy on the track jolted him into realizing just how lucky he’d been.

On Aug. 23, 2015, veteran driver Justin Wilson was struck in the head by a large piece of debris from another driver’s car at the Pocono Raceway in Pennsylvania. The 37-year-old father of two young daughters suffered a traumatic injury and was rushed to the hospital. Hinchcliffe was at the track that day, watching the race from the Schmidt Peterson bus. He knew Wilson and his family very well. He and Stefan Wilson, Justin’s younger brother, lived together in Indianapolis for a while. When Wilson’s parents arrived at the airport, Hinchcliffe picked them up and brought them to the hospital. He stayed there through the night and into the next day, when Wilson passed away. His death was a wrenching shock to the tightly knit racing community.

Hinchcliffe had learned to accept the inherent risks of racing early in life. He was just 12 when he watched Greg Moore lose control of his car and crash into a wall at the California Speedway in 1999—the driver from Maple Ridge, B.C., was pronounced dead at the hospital—and he carries the memory of his idol with him to this day. (He wore a pair of Moore’s red gloves at the Indianapolis 500 in 2012, and there is currently just one trophy on the mantel above his fireplace: the one Moore earned for his first CART series win in 1997.) But he still had trouble dealing with Wilson’s death.

Immediately after the fatal accident in August, Hinchcliffe found himself getting angry each time he heard others suggest that his friend would have wanted to die on the track, because he was doing what he loved. “It’s a cliché thing, every time a guy dies in a car,” he remembers thinking. “He’s not here to answer that question, is he? How do you know that? No one ever asked him that straight to his face.”

But as he started to process how fortunate he’d been to survive his own accident, Hinchcliffe decided it was time to ask himself the same question. As he and a few other drivers sat around talking about what had happened, he just came out and said it: “Would you be OK if you went in a car?”

And one by one, without hesitation, every one of them said yes. “That’s just what we’re like. We’re all wired wrong,” Hinchcliffe says. “I mean, it’s not the way I want to go. I want to die in my sleep at the age of 94. But I would be totally OK with [dying on a race track]. I would 100 percent accept that.”

track scars Hinchcliffe was going 320 km/h when his suspension snapped and his car hurtled into the wall on the third turn at Indianapolis Motor Speedway

In late September 2015—four months after his crash—Hinchcliffe climbed back into a race car to drive a test run at Road America in Wisconsin. His weight was back up around 165 lb., but he was still working through his recovery. He’d only been able to start exercises with his neck a few weeks earlier, and as he climbed into the tub of his car for the first time since he’d been skewered to it, Hinchcliffe was anxious. It wasn’t fear. It wasn’t even apprehension. He was worried that, somehow, he wouldn’t have what it took anymore. That somewhere inside him, something he couldn’t see was broken. At 300 km/h, the tiniest malfunction—mechanical, physical or mental—could mean the difference between winning and losing, and, yes, living and dying. “It’s all about the illusion of control,” Hinchcliffe says. “If there are 1,000 variables in a race, you control 10. The rest, you’re just along for the ride.”

Despite all that, he got in the car. Back in the seat. Back on the track. He put the car in gear, pushed down on the gas and he was off. His crew watched quietly, nervously, as he accelerated through the corners and ripped down the straightaway on the famous course. His crew chief called him over the radio: “OK, Hinch you can come in now.”

There was a slight pause, a crackle over the radio, and then a loud, triumphant shout. “I am never coming in!” he said. “Ever!” A blink, and James Hinchcliffe roared on.

This story originally appeared in Sportsnet magazine. Additional photo credit (crash image): Jimmy Dawson/The Indianapolis Star/AP