DUNEDIN, Fla. – Roaming the outfield for years and years, Devon White could never really lock in on what made Rickey Henderson so effective on the base paths. Obviously, he knew what a terror the greatest base-stealer of all time was and admired Henderson’s speed, but it wasn’t until 1993, when the Toronto Blue Jays acquired the left-fielder in a deadline deal, that the graceful centre-fielder picked up the nuance and subtleties that allowed the truly elite to excel.

“With Rickey, he was just a special athlete,” says White, himself an accomplished base-stealer with 346 bags to his credit. “At a young age, he was mostly anticipation and his speed, but the older he got, because of knowing the pitchers and his first two steps — just incredible as far as max speed — it was just a reaction. He’d see something and then he goes.”

Knowing the secret of Henderson’s success doesn’t make it much easier to comprehend, though, and the more time that passes, the more staggering his numbers become. A record 1,406 career stolen bases — 468 (!!!) more than Lou Brock, who sits second — at a success rate of 81 per cent. A modern-era single-season record of 130 swiped bags. Ten years of at least 65 stolen bases, three of them at 100-plus. A season of 37 steals at age 40, plus 36 more at 41. For context, consider the major-league leader in 2018, Whit Merrifield of the Kansas City Royals, swiped just 45 bags, a total that was 11 more than his American League-best 34 from 2017.

[snippet id=3305549]

While any comparison to the greatest leadoff hitter ever is bound to be lopsided, part of what makes Henderson’s career increasingly hard to fathom is a bigger-picture trend: stolen bases continue to decline across a game being reshaped by data-driven decision-making.

Last year, the 30 big-league teams combined to steal 2,474 bases in 3,432 attempts. Both totals are the lowest in the majors since the 2,258 taken in 3,290 tries during the strike-shortened 1994 season. In 1979, when Henderson debuted with 33 steals in 89 games for the Oakland Athletics, the 26 major-league clubs stole a total of 2,982 bases in 4,579 attempts.

By 1987, with Vince Coleman and the go-go St. Louis Cardinals also ripping things up, baseball was up to 3,585 in 5,114 tries. Even as teams have steadily become more efficient at stealing — the success rate in 1977, when the Blue Jays came into existence, was 63 per cent, while in 2018 it was 72 per cent — they’re doing it far less often. As a result, Henderson doesn’t even pause when asked whether he could run the way he once did if he was playing today.

“No, I don’t think so, because they got a time [on the pitcher’s delivery], they tell you what to do half the time,” says the Hall of Famer, now a special instructor for the Oakland Athletics. “I got a lot of guys, a lot of kids, that can flat-out run, flat-out fly. But they get on the base paths, they ain’t got a clue what to do on the base paths. Because now you get out there and all of a sudden they’re saying that this pitcher is too fast for you to even try. So what they do is shut it down. They don’t even use their instincts and now it makes them lazy.

“The kids today, they say ‘How you do it?’ And I say, ‘I couldn’t do it the way they’re doing it now because they’re making your call, they’re making the decision before you’re making decisions … They’re too worried about giving up an out,” Henderson continues. “They think they helping them a lot. I think they’ve taken a lot away from them because you can learn more if you go out there. Just like if you go to school, you go out there and read your book and learn what it is, you’re going to learn more instead of the teacher just telling you what to do. And I think that’s what they’re doing in baseball.”

DOES IT PAY TO TRY TO STEAL?

Generally, there are two key factors attributed to the demise of the stolen base. One was the steroid-era move away from the speedy, athletic types toward lumbering, cement-sack power hitters who could provide instant offence but often little else. The other, which is tied to the first to a degree, is an improved understanding of the game through analytics, which offered an objective contextualization of an out’s value and the risk-reward in running wild.

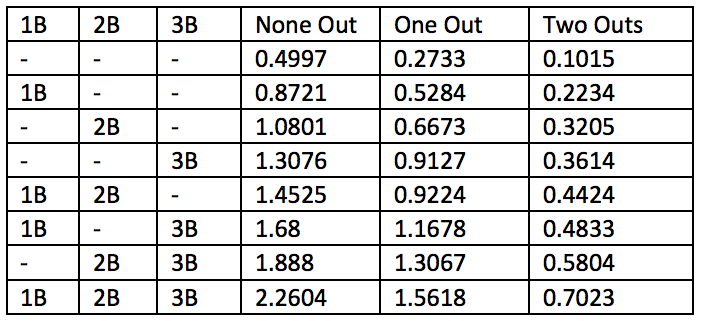

The simplest way to look at things is through a run expectancy model. The numbers vary from year-to-year but stay within a relatively narrow band, so let’s use the 2018 data compiled by Baseball Prospectus.

With a man on first and nobody out, a team could expect to score 0.8721 runs in an inning. If that runner successfully steals second, the number rises to 1.0801. But that increase of 0.208 is grossly outweighed by the decrease of 0.5988 if they get caught and leave their team with the bases empty and one out. Essentially, while a successful steal may incrementally help your team score a run, getting thrown out far more significantly hurts its chances of crossing the plate.

Combine that negative with the potential impact not scoring a run has on your team’s win probability (another advanced metric) in a given game and the risk becomes even less attractive. Add in the frequency with which balls leave the yard these days and you can understand why teams are reluctant to run.

“Most managers now realize that if you’re not stealing at an 80 per cent success rate, you’re harming your team, you’re harming your chances to score more runs,” says Blue Jays general manager Ross Atkins.

The full comprehension of an out’s value is pivotal, too. Back in the day, teams would regularly bunt a leadoff man on first over to second in order to take two shots at knocking him home. But outs are hard to get and making each one as taxing on the opposition as possible became a widely used strategy around the turn of the century, when the so-called “Moneyball Era” spread through baseball. Batters who could really draw out an at-bat were coveted for their ability to run up pitch counts on opposing starters, leading to the insertion of mediocre relievers offences could then light up.

Under that approach, very rarely did risking an out for 90 feet of progress via steal make sense. And the same goes for trading an out to advance a runner via sacrifice bunt. Between 1977 and 1994, roughly one per cent of all plate appearances resulted in a sacrifice bunt. That number dipped down to 0.85 per cent by 1999, dropped further to 0.80 per cent in 2012, and has steadily declined since, down to 0.44 per cent this year. The Blue Jays had only five sacrifice bunts in 2018, the lowest total for a team since the stat started being recorded in 1894. The wild-card Athletics were right behind them at six while the Los Angeles Angels and World Series-champion Boston Red Sox tied with seven apiece.

Essentially, sac bunts are now reserved for late-game, leverage situations when a team needs to play for a single run to either tie a game or take the lead. As a result, you get clubs taking fewer risks on the base paths and protecting outs at the plate while batters swing for the fences, in part to get the ball over shifted infield defences, but also because there is no more efficient way to score runs than via the long ball. Teams are always looking for ways to exploit weaknesses, but only in ways that minimize the risk of surrendering of an out.

Theoretically, all the data available today would have only made Henderson’s base-stealing more effective, with detailed scouting reports listing each pitcher’s delivery time to the plate and readily available video to seek out tell-tale signs in a windup. Yet he’s adamant when he says, “I don’t think I would want all the information,” believing players back in his day were adept at building up their own mental databases by closely watching what was happening on the field in front of them, honing an instinct they could rely on when it was their turn at the plate, on the mound or with the glove.

“I think they need to take away some of the information, let the kids go back and learn the game, and then I think they’d be better off,” says Henderson. “Nowadays, they’re not hitting the ball well, you’re looking at a .230, .240 average … They talk about the home runs, and they got this launch angle, launch angle, launch angle. What does the launch angle really be? Launch angle means you’re trying to hit the ball out of the ballpark. How many fly balls are you going to hit with the launch angle? You’re not going to be on the base paths because you don’t learn how to put the ball in play when the time comes.”

To that point, in 2018 there were more strikeouts (41,207) than hits (41,018) for the first time ever in Major League Baseball. Even with a drop to 5,585 homers from 2017’s record 6,105, the game is still at the upper end of the steroid-era band for dingers. Conversely, on-base percentage is down across the game, from a peak .345 in 1999 and 2000 to .318 this past season, tied with 1988 and 2013 for the third-lowest total since 1977.

Adding to the cycle is that the focus in player development, understandably, is on hitting the ball, and not on the basics of base-running, which can be hard to teach because it’s impossible to simulate the anxiety inherent to real-time decision-making in game situations. Base-stealing, on the other hand, “is a little bit easier because you’re looking for moves, you can watch video over and over of a pitcher’s move, and you can practise that skill more readily,” says Ross Atkins. “And you can argue it’s not done enough.”

Like most base-stealers born of this era, highly regarded Blue Jays prospect Bo Bichette employs a more analytical approach when he takes off, rather than relying on traditional methods.

“Honestly, being successful stealing bases is not only about getting good jumps and having instincts, it’s actually about math, knowing how fast pitchers are to home, knowing how fast the catcher is to second,” says Bichette, who went 32-for-43 on the base paths last season in 131 games with the double-A New Hampshire Fisher Cats. “If you can put those two together a lot of times you can know you’re going to be safe.”

That kind of talk makes Henderson cringe. He hates the reliance on a pitcher’s delivery time and he loathes the one-size-fits-all approach that results. Sure, a pitcher may be fast to the plate, but part of what makes a talented base stealer successful is his ability to disrupt a pitcher’s regular rhythm, to force him out of sync.

“I get the guys on the clock, they go, ‘OK, this man is 1.29, 1.3, you can’t run off of him,’” says Henderson. “You ain’t never gave the man a chance to run off of him. Did he find something on the pitcher that he can get a better jump and make the time a lot higher? They shut them down before it gets [to that point]. So that’s when I go back and say, ‘You’re not giving a guy a chance [to use] his instinct, what he can do.’ I think if I was on the base path and you tell me under a 1.3-something I can’t run, then I’ll be puzzled too.

“Why would we want to learn the same thing as one another and we’re not the same type of player?”

RICKEY HAD A JEDI MASTER

Sure, Henderson had ability like no other baserunner in baseball history. But he also had a good teacher in manager Billy Martin, who both wanted him to run wild on the bases and helped him become more effective at doing it. In 1980, their first season together, the late Martin initially forced Henderson to wait for a go-ahead to steal, which didn’t always sit well with the then 21-year-old.

“I said, ‘if I’m waiting on you to give me a sign, I could have been on second and third by then,’” Henderson recalls with a grin. “He said, ‘But I wasn’t ready for you to steal, because the pitch was so, so close.’”

As Henderson became more and more comfortable, he became less and less and patient. He remembers one game where “I’ve got a pitcher out there, I read him, every time I break I got him beat, I got him beat, you still ain’t giving me a sign, so I’m looking from first base like, ‘what are you waiting on?’” he says. “So I said, ‘OK, I’m just going to run.’ And I stole the base. I came in and he said, ‘Did you miss the sign?’ I said, ‘No, I thought you gave me the sign. I guess I missed that sign.’ He said, ‘You better be safe every time you miss the sign.’”

One of Martin’s skills was anticipating a pitcher’s sequencing, and he would regularly send Henderson when he believed something soft was coming. Henderson finished with 100 steals in 126 attempts in 1980, his first full season, and after swiping 56 bags in 108 games the next year, Martin approached him in the spring of 1982 and said, “We’re going to break the record.”

Henderson’s wanted to know how. “He said, ‘I’m going to tell you when they’re going to throw a breaking ball and that’s when you can run, and then when you can pick out any other time, you run.’ So every time I got on base I’d look in the dugout and see what’s happening. They throw a breaking ball, I’d run. So it was a really a one-two combination.”

Eventually, other teams realized what they were doing, forcing them to devise different strategies. Martin would say, “They’re looking at me too much. I can’t give you the pick. So I’m going to give it to my coach and he’s going to be way down on the other end. Look at him.”

Henderson stole a modern-day record 130 bases, in 172 attempts, that season.

“Shoot,” says Henderson. “I give him a lot of the credit.”

A similar arrangement is hard to imagine these days, and Henderson has to reconcile that in his work with the Athletics, who have the second-fewest stolen bases this century at 1,386 — a mere six more than the St. Louis Cardinals.

“I have conflicts about it, but I’m in the organization,” Henderson says. “We got to teach what everybody else teaches and you got to be able to live with whatever they’re teaching and try to explain it the best way you can…

“That’s the way the game is.”