TORONTO – In the second inning last Saturday afternoon, Russell Martin took a 94.2-m.p.h. fastball from Yu Darvish off the left elbow, glowered at the right-hander as he slowly walked to first base and, contemptuously, put his finger to his lips to shush down a chirper in the Texas Rangers dugout.

Given the Toronto Blue Jays’ testy recent history with their rivals from the American League West, you can understand why the veteran catcher might wonder about potential intent. In that instance Martin didn’t feel Darvish threw at him – “they were just trying to pitch in,” he says – and the glare was rooted in gamesmanship, rather than vengeance.

“Sometimes I’ll give them a stare just to be like, ‘Hey, don’t go back in there, if you go back in there we’re going to have issues,’ so I can look for a pitch out over the plate, kind of play that mind game a little bit. You can kind of dictate a little bit the next at-bat,” explains Martin. “It takes a really brave, brave person to keep going back in there after they’ve hit you and you’ve shown that you’re pissed off. If they do it, more power to them, because it is part of the game.”

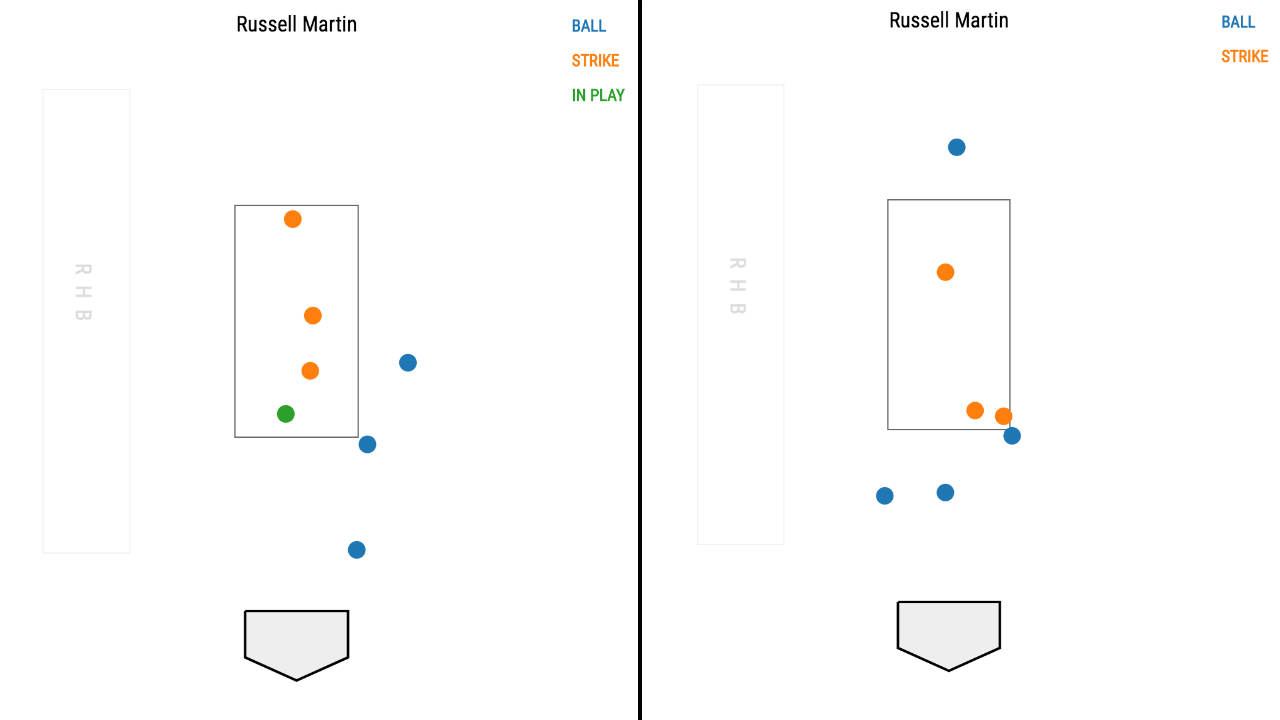

Martin’s displeasure apparently registered with Darvish as in their next two encounters, the catcher saw just one pitch on the inner half of the plate, a two-seamer that missed low. He collected a single in the fourth and a walk in the fifth, so, well played.

The incident demonstrates one way a hitter can seek recourse after getting struck by a pitch, but the calculations change dramatically when a pitcher intentionally throws at a batter, the way San Francisco’s Hunter Strickland did to Nationals star Bryce Harper to trigger a wild brawl Monday.

Really, when a batter gets hit on purpose he has no good options, underlining the disparity in power with pitchers, who can instigate trouble and face no real repercussions unless the target decides to charge the mound. The discipline handed down by Major League Baseball on Tuesday evening, subject to appeal by both players, emphasizes that as Strickland was suspended six games and Harper four.

In reality, Strickland, a reliever still angry over surrendering a couple of homers to Harper in the 2014 NLDS, will at most miss a small handful of innings, while Harper, who did nothing but celebrate those dingers, will lose 16-20 plate appearances over 36 frames of work.

[snippet id=3319157]

That’s why hitters are essentially in a no-win situation – pitchers can throw at them for the most senseless of reasons and face little more than a slap on the wrist.

“You definitely feel like you do lose if you just get hit, the guy did it on purpose and then you walk to first base,” says Martin, speaking in general terms and not about the Harper-Strickland discipline. “You feel like you win if you charge and you get a couple of punches in, for a brief moment. Then when they penalize you for that, you feel like you lost again. So you can either win for like five seconds and get like a bunch of your teammates suspended, and nobody really wins in that situation.

“Sometimes it can kind of spark something, if the team needs a little bit of energy going through a tough time, it can kind of turn things around. But I never really feel like it’s worth it,” Martin continues. “By the time you get your one lick in, you might as well wait until after the game and wait for the guy in the parking lot if you really want to do something about it.”

Martin doesn’t advocate that approach, but the point is valid.

Charging the mound is pointless and counterproductive, but when the discipline against pitchers is relatively minimal, some hitters see it as the only recourse. As Nationals manager Dusty Baker said of Harper’s reaction after the brawl: “What’s a man supposed to do? He’s not a punching bag.”

That’s how Blue Jays first baseman Justin Smoak felt last September, when New York Yankees starter Luis Severino missed him with one retribution pitch before hitting him with a second, touching off a wild brawl during which reliever Joaquin Benoit suffered a season-ending calf injury.

[relatedlinks]

Things became heated that night when Josh Donaldson was hit on the elbow by Severino in the bottom of the first inning and J.A. Happ responded by hitting Chase Headley on the buttocks, after missing him with the previous pitch in the top of the second.

Both dugouts emptied and theoretically, depending on whose version of baseball’s unwritten rules you’re using, the tit-for-tat should have ended when Severino went after and missed Smoak in the bottom of the frame. When he threw at him a second time, both teams were ready to go.

“I was leading off the next inning and I was like, all right, you’ve got one shot, do it now, you know what I mean?” says Smoak. “When they missed with the first pitch, then it should be over, warnings should be out. That didn’t happen, he hit me on the second pitch, so it depends on the situation, whatever it calls for. It’s the heat of the moment. If you think it needs to happen, it happens, if it doesn’t need to happen, then whatever.”

Contrast that with how things played out earlier this month in Atlanta, when the Braves took exception to Jose Bautista flipping his bat and staring down reliever Eric O’Flaherty after an eighth-inning home run in an 8-4 loss, causing the dugouts to empty. The next day, starter Julio Teheran missed Bautista with the first pitch, drilled him with the second, the right-fielder took his base and that was that.

“Bats knew in Atlanta that he was probably going to get hit after what happened the night before,” says Smoak. “The guy hit him in the leg and he took his base and that was it, it’s over with now. When it keeps going on, if he went up there a second time and got hit again, that’s when (trouble starts).

“Both teams handled it the right way. They did what they had to do, Bats knew he was going to get it so he handled it the right way. But when it’s multiple times, that’s when you’re like, all right, now we’ve got to do something.”

Another thing worth remembering is that determining intent isn’t especially difficult as there’s a clear difference between a pitch that gets away and one that’s on purpose.

As Martin notes, “When the ball is four-seamed straight at you, that’s like, OK, there’s some intent there. But if the ball is coming out of the side of his hand and you can see the run on it, you know it’s not on purpose.”

And as the velocity pitchers feature continues to increase across the game, the risk of serious injury when a pitcher decides to exact vengeance for some petty slight rises, too.

Unprotected by Major League Baseball’s disproportionate discipline, hitters are left to decide when they need to take things into their own hands.

“They’re throwing 95-100, the ball could be at your head, could be anywhere. The majority of time, they get away with doing that,” says Smoak. “If we go out there with a bat or start going out there with a helmet – their weapon is the ball, our weapon is a fist. It’s scary, especially when guys throw as hard as they do now. You take one in the face or the head, that’s your career on the line.”

Harper and his fellow hitters deserve better, and it’s on Major League Baseball to better police and discipline vigilante pitchers so the victims of their vengeance don’t have to.