DUNEDIN, Fla. – During the off-season Ryan Tepera bought a house in Friendswood, Texas, a small city just south of Houston, and while he didn’t get it strictly because of the pitching mound and batting cage in the backyard, that certainly was part of the appeal.

After all, the Toronto Blue Jays reliever came out of the 2018 season intent on making some changes in his delivery and refining his repertoire, looking to better leverage his mid-90s fastball. Having his own place to work out whenever he wanted sure made things convenient. Still, he wanted more than simply a place to throw, which is why he also invested in, and set up a Rapsodo Pitching unit, which provided him instant feedback on the angles and spin of his pitches and helped lead to some refinements he plans to use this season.

“I did this all on my own,” Tepera says of his adjustments. “It’s all a bunch of stuff that I’ve researched and looked at and compared videos of mechanics to other pitchers that I feel are very like me. I was able to critique some things and look at numbers. That’s something that’s always interested me.”

Tepera’s setup at home offered a good warmup for Blue Jays camp this spring, which like that of virtually every other team in baseball, is being increasingly outfitted with advanced tools to aid on-field performance.

[relatedlinks]

Bullpen sessions in Dunedin are tracked both by Rapsodo Pitching units and Edgertronic cameras, which can shoot up to 35,000 frames-per-second and are designed for “industrial, scientific, defence and visual arts applications,” according to its website. In baseball, they allow users to break down every little movement in a pitcher’s motion and release point. Set the FPS rate high enough and one pitch can take several minutes to watch.

The Blue Jays also have regular video cameras at a variety of angles capturing both pitchers’ sides and hitters’ batting practice rounds, while Rapsodo Hitting units sit between the mound and home plate tracking exit velocity, launch angle, spin axis and more.

Collecting the data, of course, is the easy part and the challenge for all teams is how to effectively extract information that is both easily understandable and applicable for players to employ on the field.

There’s a learning curve on that front across all sports, at the risk of stuffing players’ heads so full of data that it interferes with, or detracts from performance.

“The competitive advantage of having more information and numbers than other organizations is gone. Everyone has it. Now the competitive advantage is how do you get that information to be actionable,” says bullpen coach Matt Buschmann, whose data-coaching savvy led to his Blue Jays hire. “For a lot of players, and I’ll keep to the pitching side, to start it’s really just going, ‘Hey, you can objectively understand what stuff you have, why it does the things it does, and work backwards from there.’

“That’s kind of your jumping off point to going down the good rabbit hole, not the bad one.”

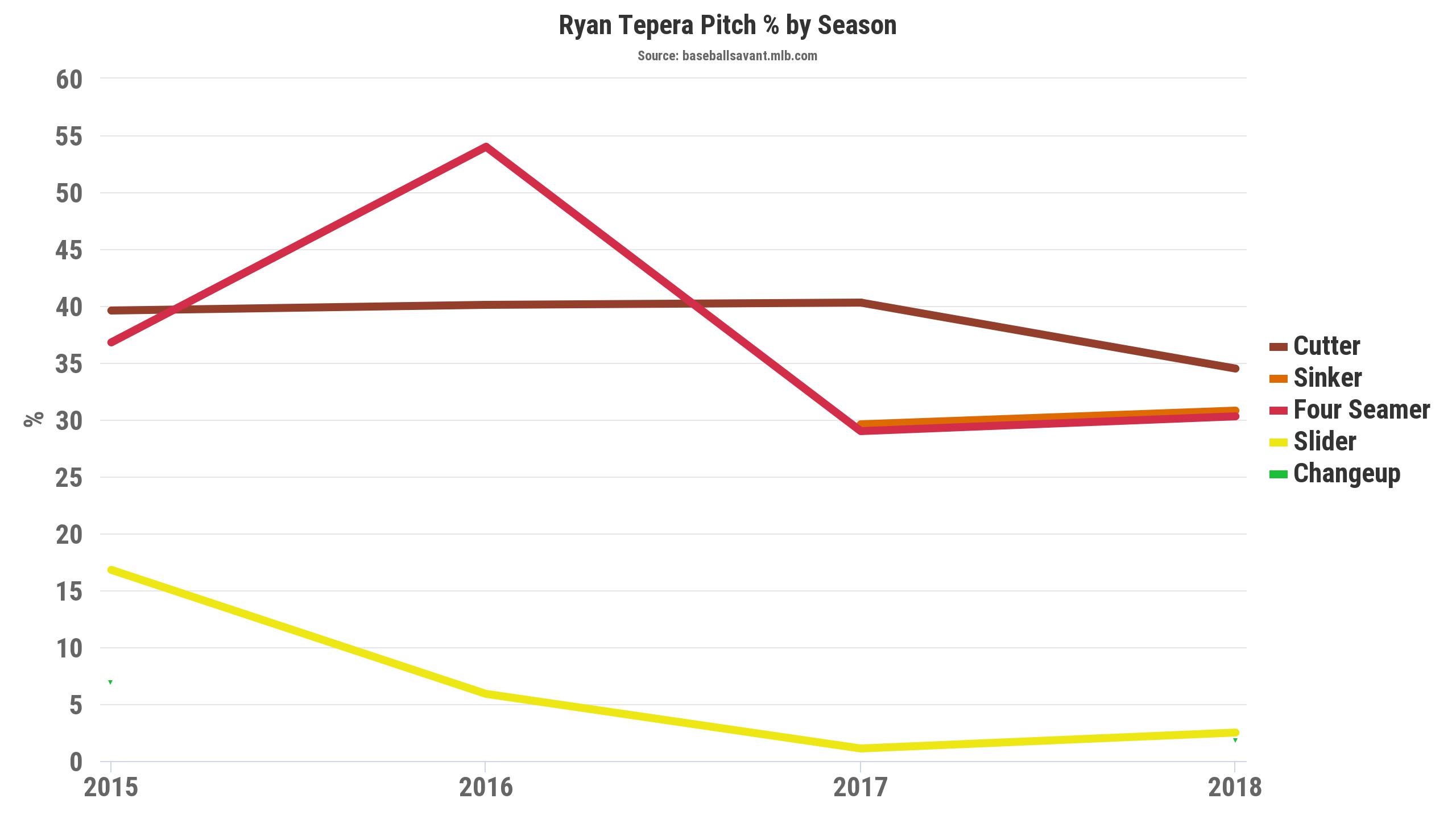

Tepera used his Rapsodo unit — a high-tech camera and radar monitor encased in a protective shell that sits six feet behind the tip of the plate and retails from $4,000-$4,500, before various add-ons — to try develop a slower slider, along with a split/change. Last year, Tepera primarily relied on three pitches, a cutter (34.5 per cent), sinker (30.8 per cent) and four-seamer (30.3 per cent), with a handful of sliders and changeups.

In analyzing his repertoire, Tepera felt he needed a pitch to complement his cutter, which breaks away from righties and in to lefties. That’s where the split/change comes in. “I want something that can go the other way,” he explains, “something that can basically come in and the hitter has to pick is it going this way or that way, but something changing the pace at the same time.”

The slider, which remains a work in progress, is meant to play off his fastball, coming in on the “same plane but, slower than my hard slider.” The Rapsodo data provides detailed feedback on what the pitches do that the naked eye can’t pick up. “It showed me spin axis and spin efficiency,” he says. “Those are the key numbers in throwing a slider.”

While spin rates are publicly available, spin efficiency right now is not, and that piece of data can be especially revealing.

![]()

Having a high spin rate on a four-seam fastball can be an indicator of a quality pitch, but having an efficient spin — 100 per cent efficiency is a totally vertical ball rotation — correlates to what hitters sometimes describe as late life on the ball. For sliders, a spin efficiency in the mid-30s tends to generate the most effective combination of sharp break and drop.

Getting instant feedback on each pitch allows pitchers to identify the release point that generates the ideal spin efficiency, and then try to replicate that exact motion on subsequent deliveries. It also helps a pitcher find out if the way the ball comes off their fingers is generating the desired results.

“There are certain spins you can change on sliders, not necessarily rotations per minute, but the spin axis and spin efficiency can go up,” says Tepera. “It’s all about hand placement. It’s trusting the grip and throwing it, and manipulating your hand when you’re on top of the baseball and when you release. It all has to come out of the same slot.”

As Tepera worked on developing his arsenal, he concurrently studied video of pitchers he felt he shared some mechanic similarities to, with the aim of refining his delivery. That led to some changes that aren’t major, but fans watching closely will likely notice three areas of difference.

First, his set-up is different, transitioning from a straight up starting point (see gif below) to a more hunched over stance akin to that of teammate Ken Giles.

“I felt like standing straight up I was swinging and almost falling backwards to where I had to swing,” says Tepera. “Now I’m in a little bit more of an athletic stance.”

Second, is that he cleaned up his initial hand motion, which would start with him pulling the ball from his glove and then tapping it back amid his windup (see gif below), something he’d always done and identified as a potential trouble spot.

“Looking straight on (from the batter’s view), I was actually showing the hitter half of the ball, so they can see grip, which wasn’t a big deal when I was just throwing fastball/cutter because it was such a similar grip,” says Tepera. “But starting to throw the slower slider and the splitter/change, if I tap, showing them half the ball is not a good thing.”

Finally, in studying pitchers like New York Yankees reliever Chad Green, he sought to refine how his lower-half works in order to reduce the swing in his leg drive (see gif below) to ensure better direction to home plate.

“I’m still swinging, but I’m trying to drive that left heel and left hip pocket down the mound, more straight down instead of, there are times I’ll pick up my leg and I’ll come out (swinging leg from third-base side of mound to first). When I come up and down (with his front leg), that toe should be back still turned (inward) and cocked, and that creates that coil action.”

Tepera spoke with both pitching coach Pete Walker and Buschmann over the winter to keep them updated on his work, and they also discussed sequencing and how to more effectively play off different pitches in his repertoire.

Buschmann’s approach with a player diving into data the way Tepera has is to “let them keep going. That’s how we learn. I can tell a guy that something will or won’t work, but he’s got to know for himself. If he’s taking initiative to learn, that’s great.”

“Realistically, players are going to look for competitive advantages,” continued Buschmann. “It’s just making that accessible to say (data) is one tool that can be a competitive advantage and maybe it helps a handful guys. There are going to be guys who don’t do it and they’re still going to be really good major-league pitchers. That’s the kind of crazy nuance of this game.

“You don’t have to do all that and still be good. You don’t have to be the most in-shape guy and you can still be good. That’s where it kind of gets messy. But if we can just take all this information and some guys get better from it, that’s great.”