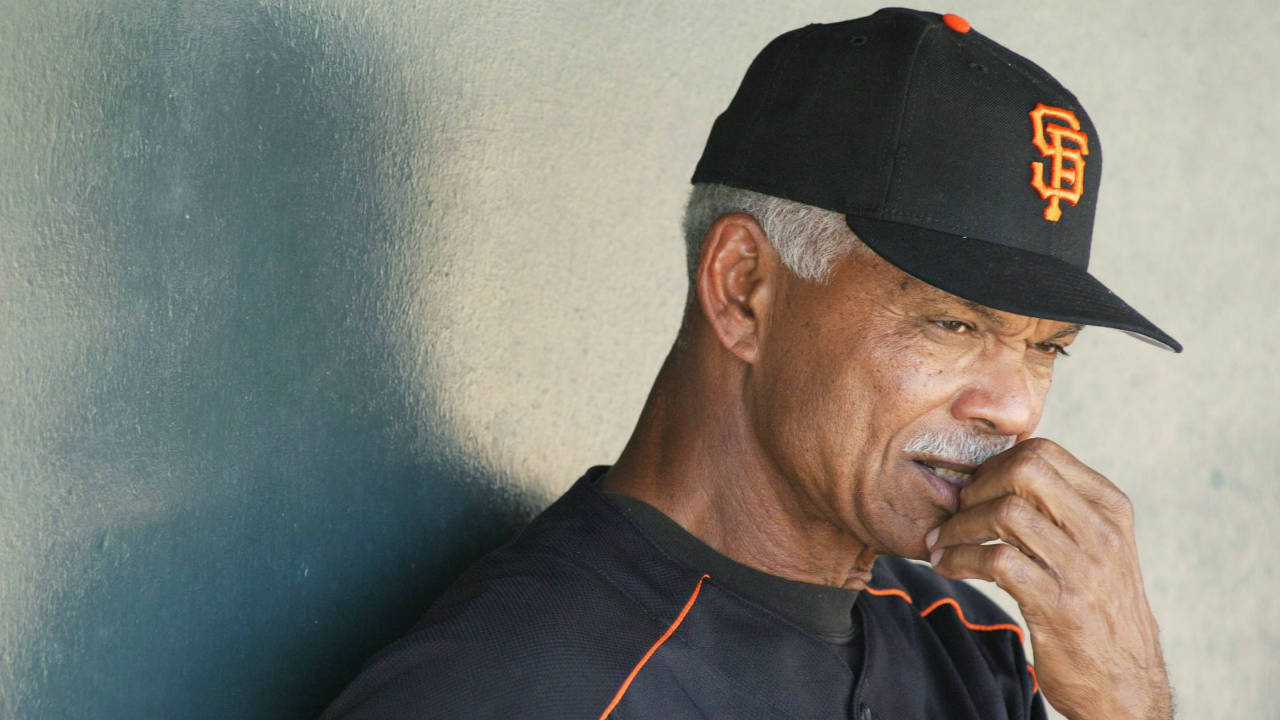

Felipe Alou never doubted his abilities as a manager, even as he was passed over again and again when big-league teams had an opening, even as he wondered whether his opportunity would ever come.

In the minors, he’d traded wits with Tony La Russa in the Southern League and Jim Leyland in the old American Association, more than holding his own against two of the top managerial “it” prospects at the time. Yet while both found their way to the big-leagues during the 1980s, Alou spun his wheels in the Montreal Expos system, routinely developing good players while posting winning records.

The landscape was impossible to ignore. In 1938, Cuban Mike Gonzalez became the first Latino manager in baseball when the St. Louis Cardinals hired him on an interim basis after firing Frankie Frisch. Ray Blades was hired the next season and when he was fired in 1940, Gonzalez took the helm for another six games before Billy Southworth got the job. It wasn’t until 1969, when the expansion San Diego Padres hired Preston Gomez, that another Latino managed in the majors. He logged 875 games with the Friars, Houston Astros and Chicago Cubs during the ’70s and ’80s, when Marty Martinez (one game) and Cookie Rojas (155 games) were the only other Latinos to run a club.

Understandably, Alou looked around and concluded, “there really wasn’t much appetite to sign Latino managers.”

“I knew I could manage because I was doing basically the same things La Russa and Leyland were doing, but they got the chance and it took me a long time,” says Alou, who had just turned 57 when he took over the 1992 Montreal Expos after Tom Runnells was fired. “I ended up being a better than .500 manager and I was considered old. There was a big headline, Felipe Alou is the oldest manager in baseball. But sort of a door was opened at the time and now I believe Alex Cora is the guy, the big guy, because he’s a young guy that led the team right to the World Series, a dominant type of managerial job. The way they play the game now, he was ready for that. And Charlie Montoyo is ready for that. So all the Latinos can get ready for that.”

[snippet id=3305549]

Exactly how much things have changed around the majors is up for debate, but Tuesday, when Cora’s Boston Red Sox take on Montoyo’s Toronto Blue Jays, the first clash featuring two native born Puerto Rican managers will certainly be a moment worth celebrating.

Along with Rick Renteria of the Chicago White Sox and Dave Martinez of the Washington Nationals, there are now four Latino managers around the majors, making up 13.3 per cent of big-league skippers. For context, there are only 20 Latinos among the 709 men to have run big-league clubs, an astonishingly small number. Yet of the 882 players on 2019 opening day rosters (including those suspended, injured or restricted), 224 of them, or 25.3 per cent, are from Latin America. In terms of proportions, there’s still room for coaching staffs (and front offices for that matter) to more accurately reflect the game’s workforce.

Cora, perhaps, may very well be a game-changer in that regard. Back in December, Montoyo wondered if he’d gotten a more serious look from the Blue Jays in part because of Cora’s success. The thing Latino coaches need, more than anything, he says, is opportunity.

“Get a chance like (Cora) did. Get a chance like I have now. Just a chance,” says Montoyo. “That’s all I can say about it. And that’s in my mind whenever I’m doing my job. I want to do the best job I can. So hopefully somebody else gets the chance to manage, also.”

Despite the praise, Cora accepts none of the credit.

“There’s a reason the Blue Jays liked Charlie Montoyo, there’s a reason he got the job – he went to that room and impressed everybody,” he says. “In the industry, maybe they see it as a shocker that it was him but people that know his career, what he did with the Rays in the minor-leagues throughout the years, what he did in that dugout last year, we noticed. Rocco Baldelli, too.

“Charlie and Rocco did an outstanding job with the Rays and that’s why they got their jobs.”

Montoyo’s hiring by the Blue Jays, coupled with Cora’s Red Sox winning the World Series a mere three days later, set off a series of celebrations back home in Puerto Rico. The island, recovering after being ravaged by Hurricane Maria in September 2017, is an intensely proud place, passionately supportive of its own. A caravan greeted Cora as he brought the Commissioner’s Trophy over for a visit following the five-game Series win over the Los Angeles Dodgers, while Montoyo’s hometown of Florida held a parade upon his return.

“I’m still trying to understand why,” Cora says smiling when asked why the two moments resonated so much back home. “Honestly, we feel baseball-wise, if you ask people back home, we should have like 10 big-league managers. You go through the list and in my family, I still don’t understand how Joey doesn’t get a big-league job as a manager. Sandy Alomar. Charlie was there. Jose Oquendo with the Cardinals. Now Joe Espada is in the mix. There are a lot of guys from back home that feel like that. I feel like that. They’re good, they’re really good.”

In 1999, Major League Baseball implemented what’s known as the Selig Rule, named after former commissioner Bud Selig, which requires teams to interview a minority candidate for any managerial or front office opening. The goal was to force clubs to begin considering candidates who were often overlooked because their networks were outside the game’s power structure, give deserving candidates experience with the hiring process, and offer more exposure within the game to those outside the usual suspects.

Direct correlation or not, in the first decade of the new century Tony Pena, Carlos Tosca, Ozzie Guillen, Manny Acta, Fredi Gonzalez and Edwin Rodriguez were all entrusted with teams. Guillen became the first Latino manager to lead his team to a World Series championship when the Chicago White Sox won it all in 2005.

While the Selig Rule has its supporters, some candidates have chafed at being invited to token interviews when a team had already predetermined its hire. That’s why Cito Gaston, who shamefully wasn’t hired to run another club after leading the Blue Jays to consecutive World Series championships, pulled himself from the running.

Cora isn’t against the rule, but he isn’t for it, either, since he doesn’t think it makes much sense to force teams into interviewing someone who wasn’t on their radar. Occasionally, surprises do happen and someone unexpectedly emerges, but the chances of that are very slim, leaving prospective candidates to have their hopes raised and dashed year after year. Cora remembers his brother going for an interview with a team that didn’t know Joey had attended Vanderbilt.

“I’m like, how did you not know he went to Vanderbilt?” says Alex. “When organizations start looking at us as capable and they interview you because you’re capable, not a minority, it’s going to start happening,” he continues. “In my experience, I interviewed with Texas, San Diego, Arizona, the Mets, Detroit – last year with three – I never felt I was interviewed because I was a minority. I always thought that I had a chance. The people that run those organizations stayed in touch with me and were very supportive, so I appreciated that. There was one organization that interviewed me for another job and I felt it, they just interviewed me because I was a minority. It felt like shit. I was like, ‘F— this shit.’

“Now with Charlie managing, with me managing, Espada a bench coach, we’re got a lot of people that have impactful jobs,” Cora continues. “I think people are going to start seeing us as, ‘Yeah, they can do it.’ There are no barriers. There are no limits. White, black, Latino, it doesn’t matter. He can do it because he’s capable and I think it’s going to get better.”

Felipe Alou is similarly hopeful.

“I believe Alex Cora showed the baseball world what a good manager can do, whether it’s a Latino, or an American, or a Canadian or Japanese,” he says. “It doesn’t matter the nationality or the race. But I’m glad Alex is a Latino. I knew he was a very intelligent player and a very intelligent person. You put those two ingredients together and you have a good manager.”

Although Montoyo only played four games in the big-leagues, all with the Expos, he made an impression on Alou. There was an attention to detail in his game that others lacked. Some leadership in the way he carried himself. A good manner around other players. Experience in every corner of the game. Smarts both on and off the field.

“I’m glad he got the (Blue Jays) job,” says Alou. “He’s going to help the development of the young players because he’s been around that part of the game. He’s going to do well with the older players because they will respect the fact that he’s a very knowledgeable baseball man. I know the people in Tampa and they know they lost a great baseball man.”

Cora feels the same way about Montoyo. They’d crossed paths over the years while playing winter ball and on the Puerto Rican team at the 2009 World Baseball Classic, when Cora played and Montoyo was third base coach.

That’s why when news broke of Montoyo’s hiring Oct. 25, as the Red Sox were flying from Boston to Los Angeles between Games 2-3 of the World Series, Cora immediately sent a congratulatory text message as the plane was just above Denver.

“When we got to Pasadena, he called me. ‘I can’t believe you texted me, you’ve got a lot of stuff going on,’” Cora recalls. “I’m like, ‘Come on, brother.’ I was very proud of him.”

Says Montoyo: “I don’t know what it’s like being in the World Series, but I know the pressure he’s going through. To think of me and tell me congrats and I’m proud of you, all that stuff, that was pretty cool.”

So too will be Tuesday’s Red Sox-Blue Jays matchup, a moment of history and a moment of pride for Puerto Rico, all during Boston’s home opener, to boot. Montoyo has been hearing about it from the moment he got hired.

“There’s many people coming from Puerto Rico for that game. And there’s many people that couldn’t get in the game because it’s already sold out,” says Montoyo. “It almost feels like everybody wanted to go to that game. … It’s a big deal for Puerto Rico.”

Cora’s hearing and feeling similar things.

“It’s meaningful,” he says. “I know how much (Montoyo) has worked to be in this situation and to share the same field and compete, it’s going to be cool. I know a lot of people back home are very excited about it, they’re very proud of it. It should be a fun day.”