Chavez Young loves his ice cream. Who doesn’t, right? But it genuinely means something to the Toronto Blue Jays prospect. It takes him back to Freeport, Grand Bahama, where he’s from. Back to the rough-and-tumble little leagues where he learned the game he plays professionally today. Back to how important his mother, Marinetta Young, is to him.

Young can’t remember exactly how old he was — nine, maybe 10. His team had just lost its championship game by a run. Young wasn’t as accustomed to processing baseball’s inevitable poor results at the time. He cried and cried and cried. On the way home, Marinetta, who worked as a housekeeper, stopped in to an ice cream shop and came out with not a cone, not a bowl, but an entire bucket of cookies and cream for her sobbing son.

“She gave me a spoon, and I ate all of it while I was crying — the whole tin,” Young remembers, standing outside the Blue Jays clubhouse in Dunedin, Fla. this March. “She’s always been a great baseball mom. She’s always been there for me. The good days and the bad days.”

A couple years later, Marinetta had one of the bad days. She suffered a stroke. Young was only 12.

“It was tough to go through. Very tough. But ever since, she’s been my motivation every day. It just keeps me driven. Just to do it for her,” he says. “For me, it’s bigger than just baseball. It’s life. When I make it to the big leagues, I think it will honestly bring tears to my eyes. I’ll be really emotional. Because this is what I’ve always dreamed of, you know?”

Notice that for Young, reaching the majors isn’t an “if” proposition — it’s a “when.” And he doesn’t stop there.

“I know what I want. Not just to make it into the big leagues,” he says. “I want to make it into the Hall of Fame.”

Anyone who knows Young won’t be fazed by this confidence. He plays the game and carries himself with a self-assuredness and flair that earned him the nickname “Hollywood” from elder Bahamian pro players Albert Cartwright and Champ Stewart, who loved giving Young grief for playing with the top buttons of his uniform undone, a gold chain bouncing on his chest.

And why wouldn’t Young be confident? He’s from Bahamas, a nation that has sent only six players to the majors. He’s a 39th round pick, selected 1,182nd overall in 2016 — the fourth-last outfielder chosen, a mere 34 picks from the end of the draft. He’s not particularly big or toolsy, and you won’t find him in the upper echelon of any top prospect lists. Confidence may be the biggest reason he’s gotten this far.

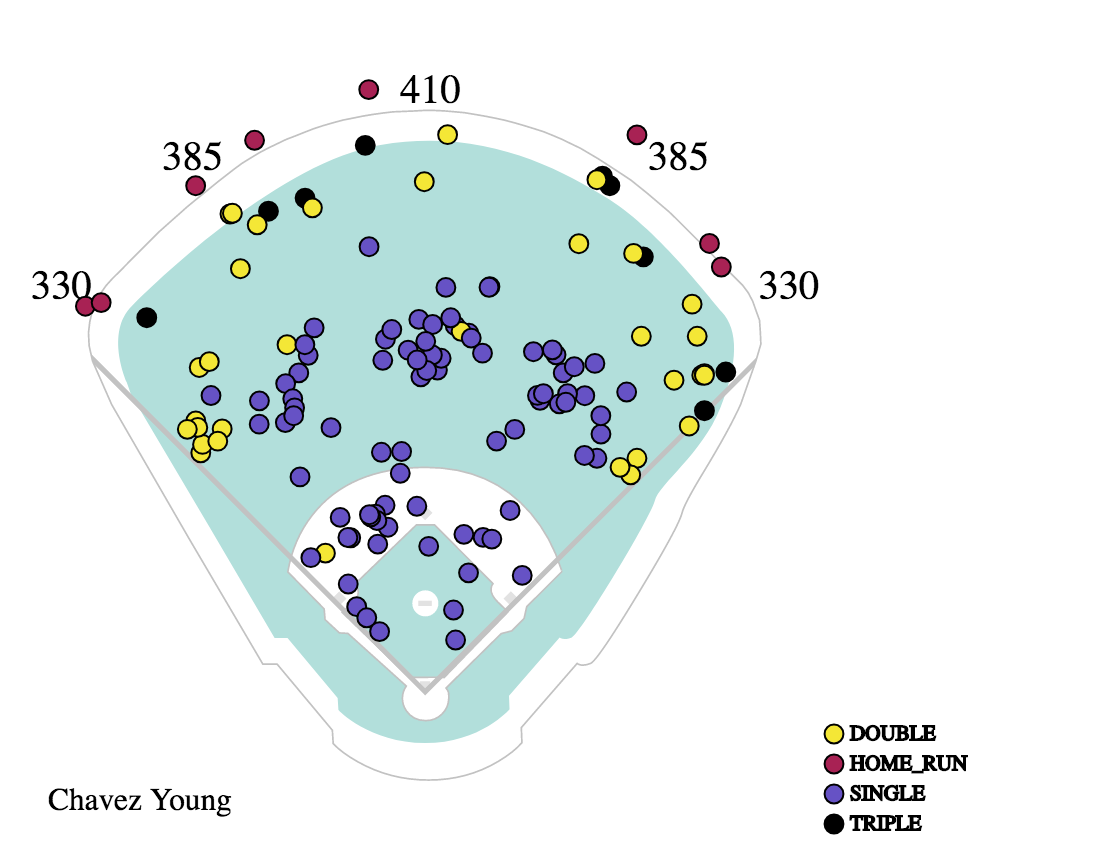

So, why are we talking about him? Well, he was the only minor-leaguer across affiliated ball in 2018 with at least 50 extra-base hits and 40 steals. He went .285/.363/.445 for the single-A Lansing Lugnuts in his first full season, leading the team in doubles, triples, steals, and outfield assists while earning a Midwest League all-star nod. And he was recently listed as possessing the best outfield arm in Toronto’s system by Baseball America.

He’s the last guy anyone was picking as a breakout candidate at this time last year. And yet, Young’s 2018 may be the most underrated, unnoticed season put up by any minor-leaguer. Not that he thinks you should be surprised by the numbers he produced.

“I know my work ethic. I know how much hard work I put in over the offseason. I’m always trying to get better,” he says. “I’d describe my game as effectiveness. Like, what I do, it affects other players. Being energetic, being a good teammate, bringing a winning attitude. I just come in and try to be myself. And try to impact this organization as much as I can.”

Here’s how it all began. Young’s father, Clayton, a plumber, had him running miles on a road near their Freeport home when he was only four, holding his son’s hand as they went, encouraging him to finish. Young eventually became a talented track athlete, excelling in the 400- and 800-metre races, but maintained an interest in team sports, playing basketball and baseball as he grew up. Something about the unorganized tee-ball games he’d play as a child always stuck with him.

“That’s where I feel in love with it. The passion was there,” Young says. “It was fun — I’d play every position all at once. I was the second baseman, shortstop, first baseman — wherever the ball was hit, I was running out there, trying to get the ball every time.”

[relatedlinks]

As he got older, baseball became more organized, although not substantially. The coaching in Bahamas is still relatively raw. There wasn’t much thought given to how players practised, little organization in pre-game routines. Young would just show up a few minutes prior to first pitch and play. Double-digit leads didn’t stop anyone from trying to steal bases or bunt for hits.

But while baseball was the passion, basketball was the ticket. A college education was the ultimate goal, so Young did his prep school recruiting tour as a basketball player. But when he found a fit at Faith Baptist Christian Academy in Brandon, Fla., that would allow him to continue pursuing baseball, he jumped at it. Two years later, he transferred to a school in Georgia for his senior season. And a year after that, the Blue Jays were using one of their final picks of the 2016 draft on him.

Now that part was a surprise. Young wasn’t following the draft, convinced he was destined to attend Polk State in Lakeland, Fla., where he’d continue to play the game he loved while furthering his education. He’d been on the phone with Polk State’s head coach that day sorting out where he was going to live. Then, the WhatsApp notifications started — hundreds of congratulations from practically everyone he grew up playing ball with.

“Bro, I was shocked,” Young says. “I came to the U.S. just to go to college. Just to get a degree. And my work ethic took me to where I got drafted. I don’t care about the round. I came from such a long way, so I treat it as if I got drafted in the first round, you know? That’s how it feels to me.”

Now, that work continues. Young’s minor-league numbers have been solid, but the switch-hitter’s game still needs polish, particularly when batting from the left side. Young hit exclusively right-handed until he got to the U.S., which is why he’s flashed more consistent power from that side and posted occasional high groundball rates. But he’s come a long way. He’ll spray balls all over the field, and has the legs to get to second if he’s held to only a single.

“I remember when I first started switch-hitting, we’d have BP scrimmage, and my teammates would legit tell me, ‘Bro, just hit right-handed,’” Young remembers. “It was really bad. But you’ve got to have confidence. People can’t dictate what your future’s going to be. I’ve had to work really hard at it. But you can’t just give up on what you think you can be.”

More than anything, Young thinks he can be the seventh Bahamian ballplayer to reach the majors. Another switch-hitting outfielder, Antoan Richardson, was the sixth, appearing in 13 games for the New York Yankees during a brief September call-up in 2014. Young will have stiff competition from more than a dozen other Bahamians currently playing throughout the minors, including Jazz Chisholm, the Arizona Diamondbacks shortstop who cracked top-100 prospect lists across the industry this year.

But Young didn’t make it this far by not dreaming big. Three months shy of his 22nd birthday, he’s starting his season at high-A Dunedin, where he’s batting second in a talented lineup and playing centre field. All he’s done is put up six hits over his first three games. It’s still a long road to the majors, but not as long as the one Young’s travelled to get where he is now.

“Making it to the big leagues, it would just be a blessing — for me and my family. It would mean a lot to my mom. Because she saw the vision when I said this is what I want to do,” he says. “I just know that whenever I make it to the big leagues, I’m going to see that smile on her face. I’m going to make her proud.”