In his story about Eric Lindros’s career and legacy, Rooting for Goliath, Gare Joyce writes that he has been telling people they’re wrong about Lindros since the early 1990s; that Lindros has been misunderstood since he was 16 years old.

To be a teenaged hockey star in Canada—“The Next One”—is pressure enough. To be perceived by many as a villain while being a teenage hockey star in this country would be too much for many.

It was not for Eric Lindros.

At 15 he was dominating players as old as 20 while scoring 24 goals and 67 points in just 37 games with the Metro Jr. B St. Michael’s Buzzers—Ontario champions for the 1988–89 campaign. That season, he also got his first taste of senior men’s competition, suiting up for two games with Team Canada, a portend of what was to come. He was making headlines as modern hockey’s next generational player: Gordie to Bobby, Bobby to Wayne, Wayne to Mario, Mario to Eric.

And then the storyline changed. Dramatically. Lindros went from teenage superstar to petulant teenager.

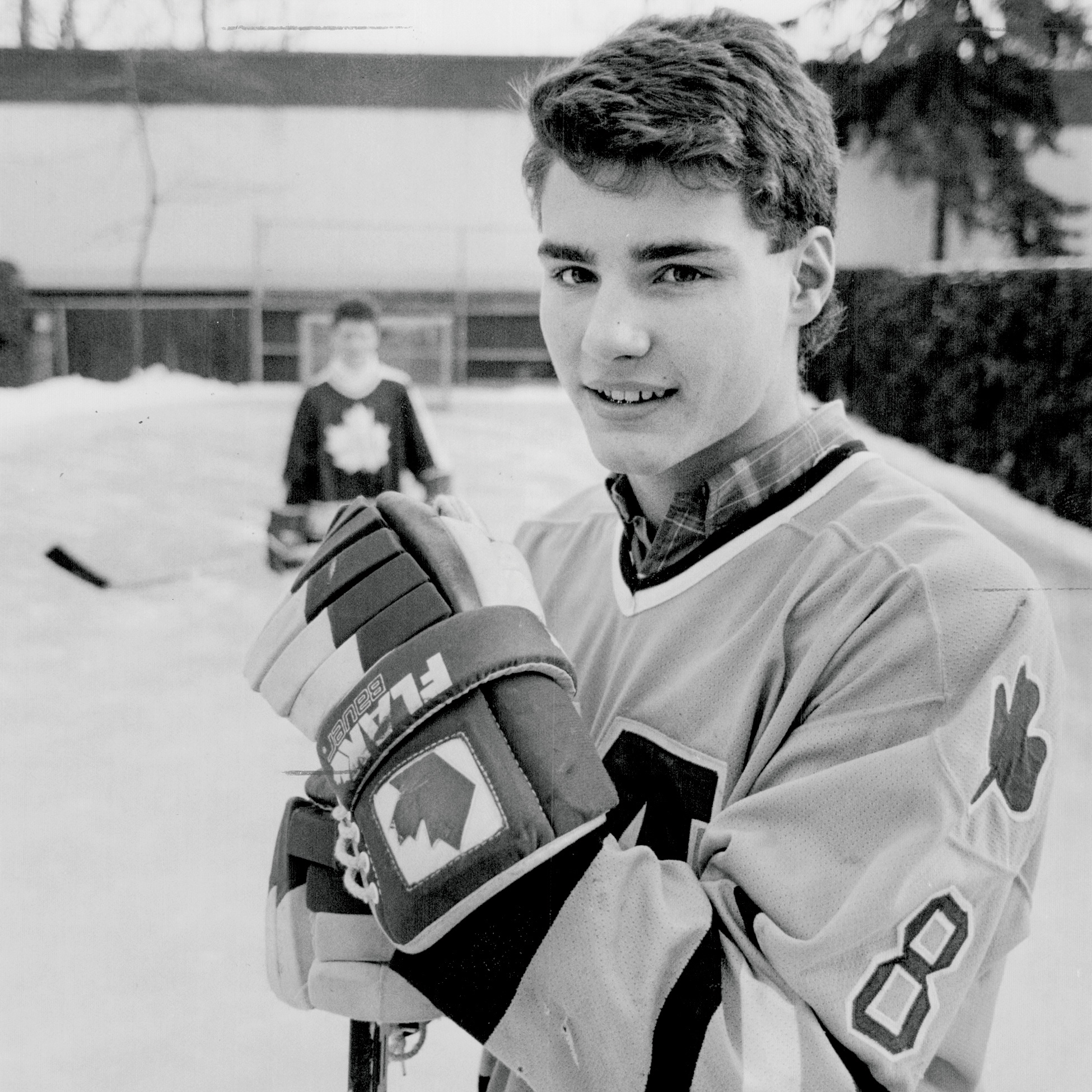

Lindros had 48 points in 27 playoff games for the Buzzers in his only Jr. B season. (Jeff Goode/Getty)

When the Lindros family told Sault Ste. Marie not to draft him, he was labelled entitled. As Joyce writes: “He wouldn’t go to the Soo Greyhounds like Gretzky had before him. He was going to play junior hockey on his terms—or his parents’. He was going to play close to home, never mind all the legends who had to move far away at 15 or 16.”

This is common practice now. By no means does every kid do it, but it’s far from rare. And, in 2016 at least, hard to argue against. Lindros was blazing a new trail for CHL players to come—one that made people in the game and outside it stand up and take notice. One that reminded everyone involved that major-junior hockey in Canada had been uprooting boys from their family and friends for generations and dropping them into unfamiliar locales.

Joyce continues: “He was hyped: Before he even played an OHL game, he was the Next Big Thing, this kid who left Toronto to play for Compuware in Detroit because he was too good.”

Follow Jeff Marek’s 2017 NHL Draft Rankings all season long.

And he was too good. While still a boy, Lindros dominated a loop that earned men NCAA scholarships, so he looked for another challenge instead of reporting to the Greyhounds and headed to Detroit and the North American Hockey League. He didn’t stay long. Lindros averaged 3.7 points per game over 14 contests with Compuware. He also added another three games with the Canadian national team and scored four goals in seven games at the world juniors—as a 16-year-old.

The Greyhounds relented and traded him to the Oshawa Generals for goalie Mike Lenarduzzi, forwards Jason Denomme and Mike DeCoff, a second-round pick in the 1991 OHL draft, a fourth-round pick in 1992 OHL draft and up to $80,000. He reported to Oshawa after the world juniors and scored 17 goals and 36 points in 25 games, then led the Generals to a Memorial Cup title with 36 more points in just 17 playoff games.

The next season, Lindros ate junior hockey alive. He scored 71 goals and 149 points in 57 games with Oshawa, and six goals and 17 points at the world juniors. The lone blemish—a celebrated one—was poetic in that his heavily favoured Generals squad was upset in the OHL final by the same Greyhounds franchise he had spurned. Lindros was named the CHL Player of the Year, was drafted first overall by the Quebec Nordiques and scored five points for Team Canada—sixth on a squad that featured 10, now 11, Hall of Famers—at the 1991 Canada Cup, as an 18-year-old who had never played an NHL game.

Of course, he famously refused to report to the Nordiques as well, and went back to Oshawa. But 31 points in 13 games later he joined the Canadian national team ahead of the 1992 Albertville Olympics. He barnstormed around Europe with them, leading all in points per game, before going back to the world juniors and becoming Canada’s all-time leading scorer at the event. He then rejoined the national team for the Games and finished second only to Joe Juneau in scoring en route to a silver medal.

Still just 18, he didn’t play another game of junior hockey. His final stat line reads: 128 regular-season and playoff games, 133 goals, 290 points and 473 PIM. And, no, you didn’t read that last number wrong. One thing people tend to forget is that because Lindros was so good and so big at such a young age, he was challenged by older players every step of the way. As a Grade 9 student with the Buzzers, he averaged 5.2 PIM per game; with Compuware the next season, nearly nine; and in his first full OHL season, 3.3. You can bet those weren’t ticky-tak hooking penalties.

Lindros finished fifth in scoring at the 1992 Winter Olympics after beginning the season with the Generals. (Amy Sancetta/AP)

Eric Lindros came along as 24/7 sports channels were starting to make their mark: ESPN was already huge in the U.S., and TSN was five years old and making inroads in Canada. It aired much of the 1990 Memorial Cup, giving Canadians a glimpse of the just-turned 17-year-old superstar-in-waiting playing junior in the Toronto suburbs. And its first broadcast of the world juniors was the 1991 tournament Lindros dominated in leading Canada to gold over the Soviet Union. You could argue that he had one of the biggest profiles in the sport, and certainly the biggest in junior hockey history—and that includes Gretzky.

Not a scout? No worries. Jeff Marek’s newest podcast is all you need.

Listen now | iTunes | Podcatchers

Lindros didn’t score the most goals or points in CHL history, in fact his name appears first just once in the OHL record book (16 GWGs in one season). But he changed the paradigm of what it meant to be a junior hockey player. He was the first of any import to balk at the OHL draft. He was the first to prove his worth with men on the international stage. He released an autobiography, Fire on Ice, before he’d played an NHL game. And just by playing, he helped launch a Canadian holidays institution.

Eric Lindros was, simply, the CHL’s first superstar.