With 11 Stanley Cups and 513 NHL goals between them, Wally Stanowski, Milt Schmidt and the late Elmer Lach belong to an era of pro hockey nearly lost to living memory.

By Brett Popplewell in Toronto, Boston and Montreal

Photography by Myles McCutcheon

This story originally appeared in the June 8, 2015 edition of Sportsnet magazine. Elmer Lach died on April 4 of that year. Wally Stanowski died on June 28, 2015, and Milt Schmidt on Jan. 4, 2016. With Schmidt’s passing, John “Chick” Webster, 96, becomes the oldest former NHLer.

Some people—doctors primarily, like the ones who brought Wally Stanowski back to life after his pulse flatlined a few years ago—might look at a 95-year-old with a water gun in his hands and a briarwood pipe dangling from his mouth as something of a medical anomaly. But the raspy-voiced, wispy-haired man with the staggered gait is more than just a curiosity, Stanowski is the oldest surviving Toronto Maple Leaf and New York Ranger, two titles he never wished for but now hopes to maintain for as long as possible.

Though he struggles to raise his left arm above his chin, hears poorly, has a pacemaker and wishes his gnarled hands worked like they used to, he doesn’t complain, not even when he’s interrupted from his lunch—a pastrami sandwich with a side of slaw. Stanowski, who was born when Robert Borden was prime minister, left Depression-era Manitoba and joined the Maple Leafs shortly after Hitler invaded Poland. He’s a man of simple tastes. He prefers plain tobacco to the flavoured stuff and enjoys the musical accompaniment of Bing Crosby while he works through a 1,000-piece puzzle.

His wisdom is terse yet revealing.

On the stacks of National Geographic he keeps by his bed: “There’s a lot of information in there.”

His secret to longevity: “Lots of beer and a good woman.”

On pigeons: “They’re the reason I carry a water gun.”

And modern hockey: “It’s terrible.”

Monday, April 13, 2015. Stanowski sits next to a photo of himself that’s hung on a pillar in the middle of a North Toronto delicatessen. He’s in his usual chair, his name engraved on its back. Stanowski has come to eat his sandwich and chat with other former Maple Leafs about the four times he won the Stanley Cup. He’d like a drink, but he can’t get it from the bar because, at 95, it’s hard to balance a beer on the trip back to his seat. So he pulls $10 from his pocket and asks to be brought “anything, so long as it’s not Coors.”

Despite the lighthearted ambience in the deli, it’s a somewhat sombre day. A player slightly older than Stanowski has just died, bumping him one step closer to becoming the oldest NHLer, a morbid fact everyone here seems overly eager to share with him. “Wally!” shouts a geriatric Leaf who is not Johnny Bower but is sitting in Bower’s seat. “You’re going to survive us all!” Then another chimes in: “If you’re the last man standing, make sure you close the door and turn out the lights!” Stanowski grabs his pint with both hands and takes a swig. His beer back on the table, he eyes the room and reflects not just on his own mortality, but also on that of everyone else around him.

“Our group’s shrinking,” he says.

Catching the attention of Ivan Irwin, a former teammate, he begins reminiscing about their shared time with the Cincinnati Mohawks. Stanowski starts in on a story about his last shift as a professional hockey player, when he flew after the puck into a corner and caught an edge on a penny some fan had tossed onto the ice. “Lost my footing,” he says, “and put my skate through the boards.”

It’s the type of story Stanowski and his fellow old-timers repeat to their dentists, barbers, grandkids and great-grandkids. But it’s rare that he finds occasion to share such memories with those who also remember.

That day in April wasn’t so different for Stanowski than the last few of September 2014. That’s when Al Suomi, a 100-year-old hardware salesman and one-time Black Hawk believed to have been the longest-lived NHL player ever, took his last breath in Chicago. His death moved a then-96-year-old Elmer Lach into the top spot, with Milt Schmidt (also 96) and Stanowski second and third, respectively.

In Lach’s Montreal-area nursing home, Rocket Richard’s former centreman was still getting over the death of his second wife when someone informed him that he’d just become the oldest living NHL player. Meanwhile, in Boston, Schmidt was confined to his room, a dangerous flu bug working its way through the halls of his nursing home, when the Hall of Famer got the call that Suomi was gone.

In Toronto, Stanowski sat in his Bloor Street residence, reading the sports pages, Dean Martin crooning loudly from the speakers on his desk. As one of the three oldest men in the game, there wasn’t much solace for Stanowski knowing that Lach and Schmidt were still out there: human buffers between himself and the honour of being the next hockey player expected to die.

Stanowski kept a photo of the 1942 Stanley Cup–winning Maple Leafs on the wall near the foot of his bed—he was the only man in it still living. It hung next to a framed copy of his career stats: 428 games played, 111 points. A good tally for a defenceman. He said they called him “The Whirling Dervish” because he once performed a dance at centre ice in Boston Garden while the rest of his team sat around waiting for the Bruins’ netminder to get his face stitched up. “The crowd had never seen anything like it.”

Stanowski ran through the particulars of his life: “My dad was a blacksmith. He would have rathered I became a blacksmith, too.” Stanowski had wanted to fly during the war but couldn’t because he was colour-blind. He said he always had more trouble defending against the Rocket than Gordie Howe, and that: “They say Howie Meeker scored five goals in one game in his rookie season, but I scored two of them!” He had so many stories to tell. “I was once offered $100 to throw a game. Guy told me, ‘If you consent, go behind the net and pretend to tie your laces.’ I didn’t do it.

“Conn Smythe didn’t like his players to have sex. He didn’t want any of us having any fun … I met my wife at a beach in Manitoba in 1942. She was a bathing beauty. She died last year. Her name was Joyce.”

Talking about his two remaining elders in the game, Stanowski said: “Milt Schmidt was a tough competitor. Elmer Lach once knocked my skate out from under me with his stick. I didn’t like that.”

After two hours of talking, Stanowski was getting tired. He grabbed his pipe, put it in the basket on his walker and headed out into the autumn air for a smoke.

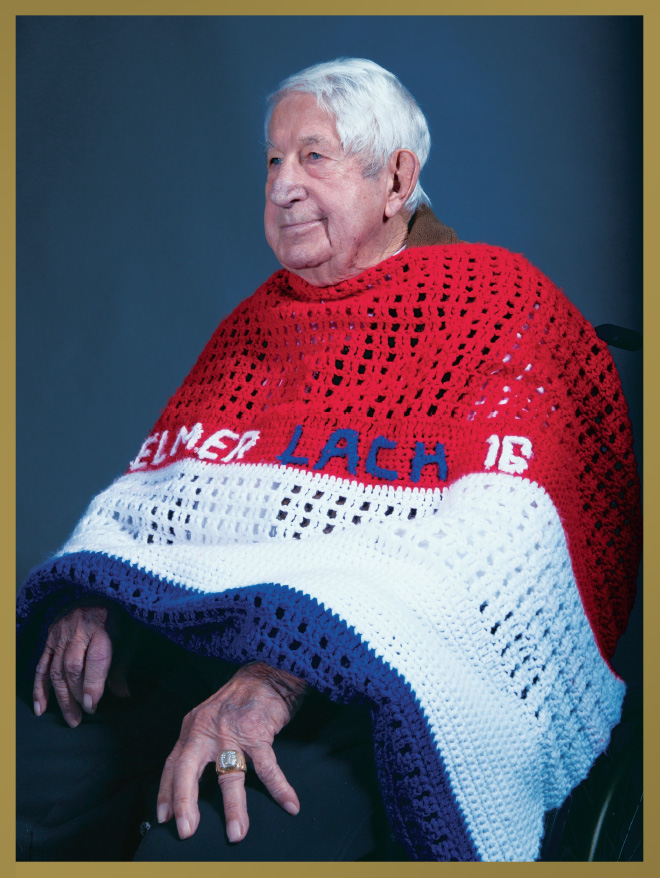

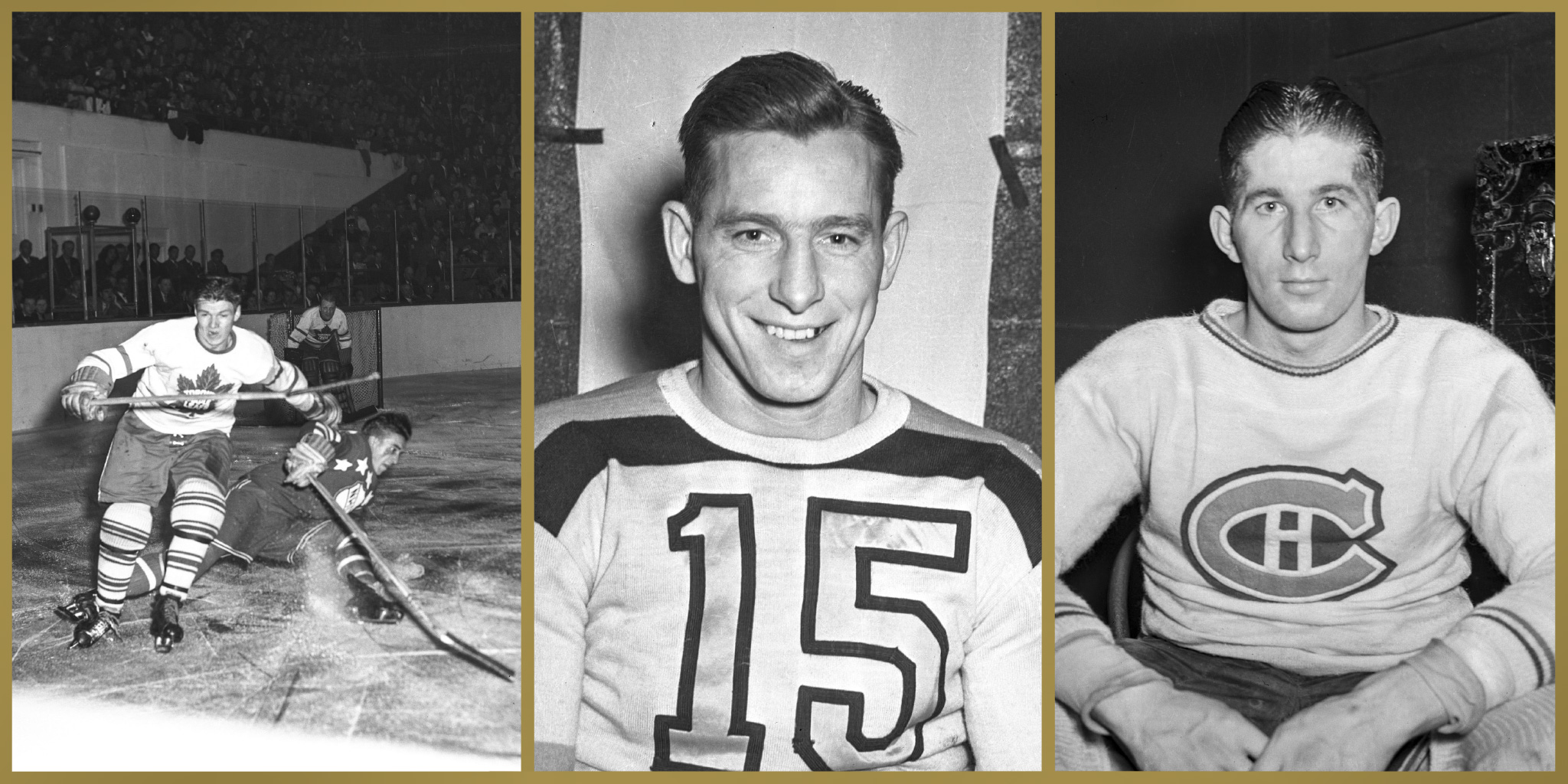

Elmer Lach Lach hoisted the Cup three times and retired as the NHL’s all-time leader in career points, but his favourite memory of linemate “Rocket” Richard happened off the ice. “Fishing. We used to fish together in the summers.”

Milt Schmidt had been out of quarantine for a month when his 65-year-old son—also named Milt, but who preferred to be called Conrad to avoid confusion with his famous father—stood at the entrance to Schmidt’s Boston nursing home, explaining that his father was having a good day and was ready to talk. Schmidt had served as the Bruins’ captain, coach and general manager in five decades with the team. He spent most of his playing career flanked by two childhood friends, Woody Dumart and Bobby Bauer, with whom he’d grown up in Kitchener, Ont. They were all of German descent, so the newspapers called them the “Kraut Line,” except for a time during the Second World War, when they were rebranded the “Kitchener Kids.” The Krauts won the Stanley Cup in ’39 and ’41 before joining the Royal Canadian Air Force and shipping off to England, where Schmidt trained bomber crews to escape the sinking wreckage of their planes should they be downed over the English Channel. Back in Boston after the war, he was named league MVP in 1951. Schmidt retired midway through the ’54–55 season, relocating directly behind the bench. Twelve years later, he was named Boston’s GM and immediately brought Phil Esposito to the Bruins, adding some front-end support for a 19-year-old Bobby Orr.

The entrance to Schmidt’s apartment was marked by a painting of kids playing shinny on a frozen pond. Conrad opened the door, and there was Schmidt—the old Bruin who was carried off the ice on the shoulders of the Montreal Canadiens after his last game before shipping off to Europe—waiting in his sitting room, looking at a trophy case featuring, among other things, four replica Stanley Cups and a framed portrait of his deceased wife.

Schmidt’s room was hot and humid. He’d spent enough time on cold rinks and now he really appreciated the warmth. He sported loafers, pressed pants and a checked shirt, and was quick to point out that he always wore a dinner jacket at mealtime. His mind was as sharp as his attire. He said: “Go ahead and ask your questions and we’ll see how much I have to say.” Moments later he was leaning back in his chair talking about how it all began 86 years ago, when he put on his sister’s skates and walked half a mile to a pond in a farmer’s field. Then he chuckled. “I got called into the principal’s office once,” he said. “I was in trouble. The principal asked me: ‘Whatever is going to happen to you, Milton?’ I told him: ‘I’m going to become a pro hockey player.’ And that’s what I did.”

Schmidt said he and Lach had been good friends, though they played for rival teams. Remembering his playing days, he curled back his upper lip, pointed to his front teeth and said: “These are not mine. These are Rocket Richard’s.” Story went that Richard broke Schmidt’s nose and teeth with his stick. The team doctor put Schmidt’s face back together, then Schmidt got on the ice again and drilled Richard. “The Rocket got up and starts skating toward me, and I said, ‘OK Maurice, you wanna go?’ And he says, ‘No no no no no no. But why you do dat?’ I says, [pointing to his teeth] ‘Because you do dat!’”

When he enlisted, he contemplated changing his name because the Germans were the bad guys, but ultimately decided, “If the Schmidt name was good enough for my family, it was good enough for me.” His family meant a lot to him. One of his few regrets was that his father never watched him play, too afraid to see his son get hurt. During the war, Schmidt and the other servicemen would gather around the radio every Sunday and listen to a delayed broadcast of Hockey Night In Canada. “I ate my heart out, thinking that I could be back there,” he said. “But the war was more important.” He lamented that the Bruins weren’t as strong a team upon his return.

He’d been one of the fastest skaters in the league but ultimately retired when he realized that the younger guys on the team were catching him on the ice. People had been calling him a legend for decades, but he never really took to the word. He said coaching was fun, but not nearly as fun as playing, and that being GM of the team during their 1970 and 1972 Cup wins had its perks. One of them being that Bobby Orr still called every year to wish him a happy birthday and a merry Christmas.

Soon the phone rang, and Schmidt leaned forward in his chair, reached over his morning’s copy of the Boston Globe for the receiver. It was Johnny Bucyk on the line, checking in with his former coach. For five minutes, Schmidt and Bucyk bantered back and forth about how poorly the Bruins had played the night before. Schmidt cut the conversation short, saying he had to go because he had company and didn’t want to be rude.

But something changed inside the old man during that call, and as he turned his attention back to the room, he looked again at the replica Stanley Cup from his 1939 win. “I can honestly say that sometimes I just sit here and cry knowing that I’m the only name on there who’s still alive.” That thought led him to his wife, Marie, whose picture was beside that Cup and who’d passed away in 1999. “We met on a blind date in Kitchener,” he said. “She was a salesgirl in a women’s store and a secretary. She was a very good skater. They gave us a name when we skated together at Christmas parties. We were ‘The Old Smoothies.’ When she got sick, I took her to the hospital every week. She used to call me ‘Dad’ and I used to call her ‘Darling.’ Now that she’s gone, I call her ‘Mother.’”

A few quiet minutes later, Schmidt circled back to Lach. It would soon be Lach’s 97th birthday, and though Schmidt wanted to call him, he no longer knew what they would talk about. Then he reached into a box of cards from the Hockey Hall of Fame. The cards each had Schmidt’s photo and career stats on the front. He turned one over, wrote a message on the back and asked that it be delivered to Lach.

Elmer Lach was three-quarters of the way through breakfast inside his nursing home on the outskirts of Montreal when his stepdaughter sat down next to him. He smiled at her, took another bite of toast and began looking for someone to top up his orange juice. He never liked to talk during meals, but he let others ramble as he ate. He was among new friends he’d made in the nursing home, men who’d spent parts of the 1940s and ’50s sitting in the stands of the Montreal Forum, watching Lach lead the charge up centre ice for the Canadiens. They counted themselves fortunate to now eat with him every morning.

He listened as his daughter explained that a man had come to see him via Boston, where he’d met his old friend and rival. Lach looked up from his coffee with an excited grin. “Milt Schmidt!” he said. “Milt was one of the best.” Adjusting in his wheelchair, Lach said he had stories to share about Schmidt but went quiet when he learned that his visitor was hoping Lach would instead talk about himself.

Lach’s humility had long been chronicled by those who followed him throughout his career. Lach had anchored the “Punch Line,” scoring 215 goals while also feeding passes to the Rocket and Toe Blake. He won three Stanley Cups, led the NHL in scoring twice and retired with more career points than any other player at the time. But he hadn’t earned the same lasting appreciation as his linemates. In retirement, he lent Henri Richard the number off his sweater and didn’t seem bothered when the Canadiens later retired it in the Pocket Rocket’s honour.

Lach scored the Cup-winning goal in overtime in 1953, but never bragged about it. “He doesn’t talk much about his playing days,” said Ronald Gilbert, his friend and neighbour at the residence. “I ask him all the time: ‘Elmer, how did you feel when you won that Cup?’ But he doesn’t really say.”

Then Lach quietly spoke: “That was a long time ago.”

Born in Nokomis, Sask., a few months after the NHL was formed and a few before the end of the First World War, Lach joined the Canadiens for the 1940 season, arriving by train from the Prairies. He remembered his first moments in Montreal and could still quote the strangers who were surprised when he told them his luggage—which consisted of a toothbrush and a handkerchief—was in his back pocket. Though the memories of his playing days were fading, he remembered the pain of the game. “I was hurt a lot,” he said, acknowledging the time he was rushed to hospital with a fractured skull and the time doctors rewired his jaw.

He spoke of his first pair of skates, which he borrowed from a neighbour, then of his mother, whom he said he could no longer picture, but whom he remembered saying “Don’t get hurt” every time he slipped his feet into his skates. “I never laced them up,” he said. “I used to just kick them off after the game.”

“What about that goal?” someone asked. “The one that won you your last Cup?”

Lach’s reticence to reminisce bothered his new friends. They really wanted to know how it felt as he threw his arms up in the air while Richard leapt into him, breaking Lach’s nose in the process. Unsure whether Lach could still remember that moment, Gilbert recounted his own memories of following that game as a fan.

Nicknamed “Elegant Elmer,” Lach was an aggressive forward who often outshone even the Rocket. The two built a lasting friendship on the ice, which they carried into old age. “What’s your fondest memory about the Rocket?” Gilbert asked.

Lach paused, pondered the question, then smiled and said: “Fishing. We used to fish together in the summers.”

For hours that morning, Lach, Gilbert and others explored Lach’s memories from the game, looking through old photographs from his life, discussing his affinity for warm beer and his thoughts on the current Canadiens—Lach enjoyed watching the team play on the TV by his bed.

Then Lach said he was looking forward to nodding off in his chair, explaining that his favourite part of the day was the end, when he got to close his eyes and fall asleep without a care.

The next morning, Lach sat back at his breakfast table with Gilbert, drinking coffee and looking at the birthday card that had been brought to him from Boston. He smiled and stared at the image of an old friend in full Bruins gear. Then he flipped it over to read the message. “To Elmer. One of the greatest. Wishing you the best.”

Lach held the card for a while, before saying: “That’s a nice card.”

Soon, he retired to the lounge outside his room for a gathering of family and friends. There he sat, sipping a warm Molson Canadian and enjoying his last birthday party as those who loved him regaled him with their own memories of his past.

Elmer Lach died on April 4, 2015. He was 97 years old. With Lach’s passing, Milt Schmidt (now 97) has become the oldest living NHL player. Wally Stanowski (now 96) is No. 2.

This story originally appeared in Sportsnet magazine.

Almost Done!

Please confirm the information below before signing up.

{* #socialRegistrationForm_radio_2 *} {* socialRegistration_firstName *} {* socialRegistration_lastName *} {* socialRegistration_emailAddress *} {* socialRegistration_displayName *} By checking this box, I agree to the terms of service and privacy policy of Rogers Media.