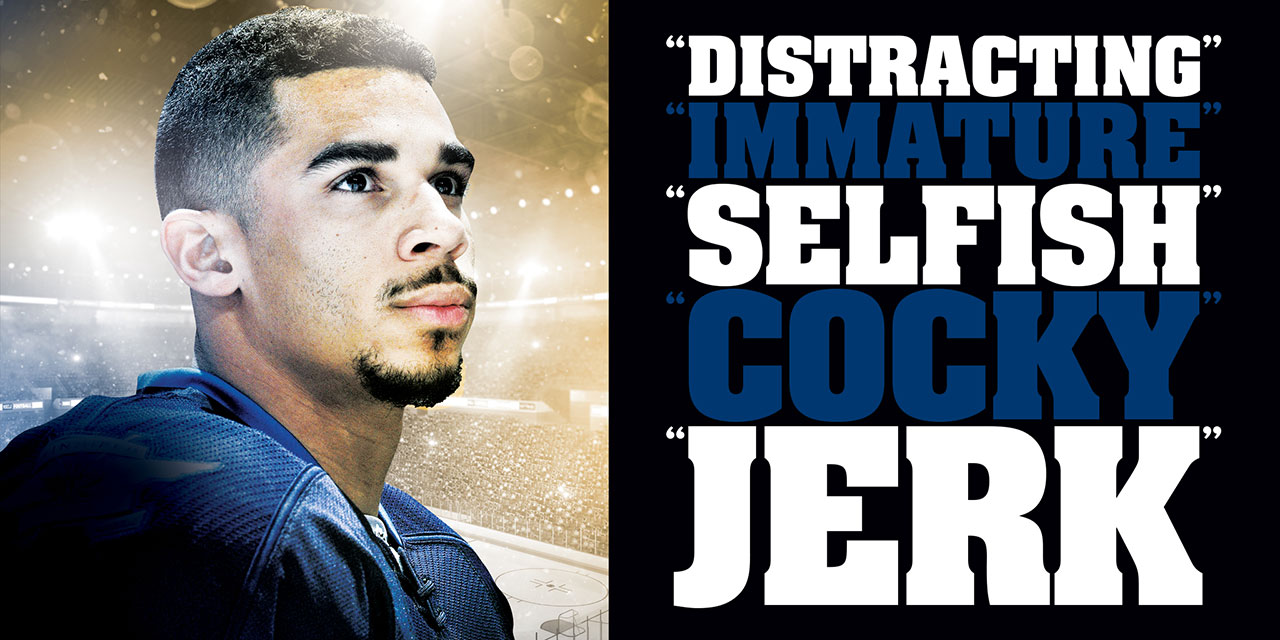

Evander Kane has been called a lot of things. But that’s not the whole story. What you don’t know about the centrepiece of the biggest trade of the NHL season just may change your mind about him.

By Kristina Rutherford in Winnipeg

Evander Kane faces the Las Vegas city skyline. It looks like early morning. He’s parallel to the floor, elbows bent, in a push-up position. He’s shirtless, but his muscular back is obscured by seven stacks of American bills that are piled on top of him. Some stacks are bigger than others. Most are held together by elastic bands.

The photo that captures this moment appears on Kane’s Instagram account on Dec. 1. The accompanying caption he chooses is simple: “#pushups.”

The next day, Kane is all smiles, addressing a cluster of reporters in the Winnipeg Jets dressing room. They’re asking “Why?” in every way they can think of. It’s an old picture, Kane says. He was just having fun, he says. He didn’t hurt anybody, he says.

This is Evander Kane. He’s flashy. He loves to get a reaction. And he has a way of making headlines like no other player in the NHL. Consider his final days in Winnipeg: Kane was made a healthy scratch after reportedly wearing a track suit to the rink on a game day. A teammate allegedly threw his clothes in the shower, and later likened him to a child in need of discipline. Kane was traded days later. And though season-ending surgery means he won’t make his debut for the Buffalo Sabres until October, Kane remains in the spotlight, the centrepiece of the biggest blockbuster in recent history. In the early days of his four- to six-month rehab, he’s more controversial than ever. But the questions remain: How much of a problem is Evander Kane? Who exactly are the cellar-dwelling Sabres getting? His misdeeds have been well-publicized. But sit down and talk to Kane, and a different picture emerges. You might even like the guy.

Kane started early, at age three or four. Most of the time, his dad, Perry, woke Evander up for practice, but sometimes it was the other way around. Father and son were regulars at 8 Rinks in Burnaby, B.C., where the 6:15 a.m. stick-and-puck sessions were drop-in and desolate. In other words, perfect. The Kanes often had the ice to themselves, or shared it with a couple of others. Perry set up cones and yelled. He never used a whistle.

Perry played Jr. A in Nova Scotia, and he wanted his eldest child to learn to stop both ways, skate backwards and have a decent shot before he started organized hockey. “He didn’t want me to be one of those kids who couldn’t stand up and couldn’t skate and couldn’t move,” Kane says. The practices were tough, but Kane understood even then that he had to put in the work. “You might not believe it, but I knew then I was gonna be an NHL player.”

Perry was adamant that they should wait until Evander turned 10 before signing him up for organized hockey, but Evander’s mom, Sheri, secretly signed him up when he was eight. They were strict, the Kane parents. Evander and his younger sisters, Brea and Kyla, who are two and four years younger than him, respectively, had to get A’s and B’s in school. Kane made the honour roll every term but says his sisters, who excelled academically, “made me feel like I was getting F’s.”

Sheri and Perry poured everything they had into their children—hockey at the North Shore Winter Club for him, competitive dance for the girls. Kane says the family didn’t have any savings. The five of them rented the upstairs of a two-bedroom house in southeast Vancouver, and Kane shared a room with his sisters. Brea and Kyla shared a bed, and Kane had his own on the other side of the room, with a couple of his hockey sweaters pinned to the wall above it. They painted his side blue and the girls’ side pale lavender. “We had some separation, which was nice,” Kane says. “At least, as much as we could.” Sure, they’d have their arguments, and he says he spent less time in there as he got older. “But it was awesome,” Kane says. “You always have somebody to talk to, and you’re always playing with somebody.”

They had a TV in there, too, and a PlayStation. “I think it made us a tight family,” Kane says. “It’s funny. I look back on it now, and everybody’s like, ‘Aaah, you didn’t have your own room when you were a kid?’ But it was fun to share a room with my sisters. I really enjoyed growing up.” He pauses. “I almost wish I could go back. Wish I could be a kid again.”

This is not the Evander Kane refrain we’re used to. That he’s named after Evander Holyfield is well-known. That he comes from an athletic family is too: Sheri played pro volleyball, and after Perry’s junior-hockey days, he was an amateur boxer. Kane’s upbringing isn’t something he’s talked about much, though. He says he’s been asked vague questions, and he gives equally vague answers. “It’s not something you just say,” Kane explains. “The thing is, it’s not like I was a rich kid who grew up in the Hamptons, and Mommy and Daddy gave me a trust fund or something like that. I’ve worked hard. And I’ve been fortunate to have the family that I have.”

The Kanes bought their first home the summer Evander turned 19, a couple of months after the Atlanta Thrashers’ fourth-overall pick in 2009—the NHL’s highest-drafted black player ever—put up 14 goals and 12 assists in 66 games, 12th among rookies. Until then, Kane considered the rental his home. In his eyes, he shared a room with his sisters until his second year in the NHL. His rookie contract, three years at nearly $1 million per, must have paid the bill for the family’s Vancouver home, but Kane won’t say so. When asked, he says, “We bought a new house.”

Hockey’s most famous money flaunter won’t come out and say he paid for his parents’ house. “It’s not something I feel I need to talk about,” he says.

This from the guy who did push-ups with stacks of cash on his back and felt he needed to Instagram it.

Front and centre A six-foot-two power forward, Kane has been lauded for his ability to force the issue in the goalmouth. He’s also been criticized for his propensity to stay in the news after the final horn.

Kane settled into a chair at ice level at the MTS Centre, wearing shorts, runners and a long-sleeved Winnipeg Jets hoodie. It was late December, a little more than a month before he became a Sabre, and it was immediately clear why Jets centre Mark Scheifele calls his former winger “a specimen”—when Kane is immobile, he looks like a sculpture. Kane’s closest friend in hockey, Jets winger Chris Thorburn, says the first thing he noticed about him when they met five years ago was this: “He looked like he’d been working out his whole life.”

Kane is easy to talk to and well-spoken. He’s open about how much he enjoys the “adult playground” that is Las Vegas and the fact that he gets a manicure and pedicure on a weekly basis (his cuticles are immaculate). And he smiles even when he doesn’t like your question, a skill he developed, he says, after being asked hundreds of times whether he was happy playing in Winnipeg, questions that persisted even after he signed a six-year, $31.5-million contract with the Jets in 2012. “I’ve learned to enjoy the process,” Kane says, grinning.

This season was far from enjoyable for No. 9, however. Kane was injured in the opener and again in December, and upon returning, he played hurt until he announced in February he’d undergo season-ending shoulder surgery, days before he was dealt. The six-foot-two, 195-lb. power forward scored 30 goals at age 20 in this league and has been vocal about the fact that he expects to score 50, but he’s put up just 29 in the past two seasons combined. That he has yet to suit up for a playoff game in the NHL—let alone get close to a Stanley Cup—reads nothing like his early career. Kane had the storybook on-ice experience for a junior hockey player: He won the Quebec peewee tournament, the Memorial Cup and world junior gold. The trifecta. And not only did Kane win the Memorial Cup, but he did it at home—at age 15.

The Vancouver Giants’ then-coach Don Hay describes Kane as “not very thick” in those days. Still, he decided Kane was more valuable in the lineup than an older player, and dressed him for five playoff games during that 2007 championship run. Brent Regner was a 17-year-old defenceman on that Giants team, and he doesn’t remember young Kane being any more nervous than he was. “Good players have that certain swagger,” says Regner, who now plays for the American Hockey League’s Chicago Wolves. “He was pretty confident, even at 15.”

Kane may have been a support player on the Memorial Cup–winning team, but in 2007–08, he had 41 points and was runner-up for Western Hockey League rookie of the year. A year later, Kane was a late addition to Canada’s 2009 world junior roster after initially getting cut. He started that tournament as the 12th forward and was challenging for a spot on the second line by the final. “That’s the belief in himself that he has,” Hay says. He calls Kane “stubborn” and “a challenge,” but adds that those qualities are part of what make him a great player. In Kane’s final Canadian Hockey League season, he was a WHL West first-team all-star and finished fourth in league scoring with 48 goals and 96 points in 61 games.

Regner takes pains to be diplomatic, but he will say that Kane’s “swagger” rubbed a few Giants the wrong way. “Maybe he took it a little bit too far sometimes,” Regner says. “But he was such an integral part of our team, so you wanted him to be pretty confident, right?”

Though Kane’s attitude might have bothered some, nobody questioned his desire. Hay is a fan of Kane because he tells his guys that if they want to win, the best players on the team also have to be the hardest-working. Kane was a great example. Regner says Kane practised like a grinder, not a skill player. Nobody disputed his commitment or work ethic then. But that changed shortly after the Thrashers relocated to Winnipeg.

In late December, when a Jets beat reporter learned Sportsnet magazine was in town to do a profile on Kane, he wondered aloud about the angle. He answered his own question: “Problem child?”

Kane has been called a lot of things. Cocky. Selfish. A jerk. In hockey circles, “distraction” is the popular term. But that’s not how teammates characterize him. In December, Scheifele was delivering straight-faced hockey talk until the “#pushups” photo came up. “He got a little ribbing for it,” Scheifele said, grinning. Thorburn brought up the time Kane “carved” the acronym for “Young Money Cash Money Billionaires,” into his hair. (Thorburn thought it said “YMCA” at first.) And the guys in the room had recently given Kane a new nickname: “Cocktails,” the origins of which Kane called a “long, long story.” Thorburn got into it: “We’ll say, ‘Let’s go for drinks or for a beer,’ and he’ll always use the term ‘cocktails.’ ‘Let’s go out for a cocktail.’ And it’s just like”—Thorburn paused to laugh—“you only hear that in movies, you know? He’s trying to be fancy and play along with his persona. We shut that down pretty quickly.”

It all seemed like playful mocking. And it continued even after he was gone. In February, while Kane was calling his situation with the Jets “unique” and welcoming a “fresh start” in Buffalo, his former team was making light of the track suit incident. When coach Paul Maurice showed up to a scrum without a suit jacket on, he told reporters that despite his dress code violation, “My clothes aren’t wet.” Of course, only the guys in that room know the inner workings of Kane’s relationship with his teammates and how it may have changed after the shower episode and the healthy scratch. Zach Bogosian, dealt with Kane to Buffalo, refers to it as “the incident,” and that’s about all he’ll say. This is as far as Kane goes with the details: “Was I wearing a track suit?” he said at his first press conference as a Sabre. “No.” Then he laughed.

Fair or not, fans associate that wet track suit and those stacks of money with Kane. But if you talk to friends and teammates, at least half the picture’s not accurate. In December, Thorburn laughed when asked whether the money pictures posted to Instagram are a good representation of who Evander Kane is. “No, that’s not who Kaner is,” he said. “He’s a very caring guy, a good friend to have. But he does wear his flashy suits, his sunglasses, his headphones. He puts on a show.”

Thorburn wasn’t surprised that Kane didn’t own up to buying his parents a house. “Deep down, he’s modest. It’s just weird, because he comes off so flamboyant on social media.”

Bogosian has been Kane’s teammate the past six seasons; they’ve grown up in this league together. “He’s a very emotional, very charismatic kind of guy, so that naturally brings more attention to a player,” the defenceman says. “Whether it was brought on by him or other people, I think his personality was really blown up—which isn’t always a bad thing—but I think a lot of people have a misunderstanding of what kind of person he is.”

If you ask Kane, here’s who the Buffalo Sabres are getting: He describes himself as “generous,” “loyal” and “kind-hearted.” He knows the average fan wouldn’t attach those adjectives to his name. And he knows he’s had a hand in this, beyond what he calls the “loud” pictures he’s posted. He says several things about him have been “made up,” but he’s never been quick to correct anyone or point out what those things are. “Too many to even pick one out,” he says. Kane will arrange his own interviews via text message (he’ll even write “lol” and use exclamation marks), but he’s hesitant to connect a reporter with his family to offer a better picture of where he came from. It could be he’s afraid of what his family might say, or what they might be asked. It could be part of that loyalty he talks about. Kane still spends his summers skating with his dad, who turned those morning practices into a business and now runs individual training sessions. Kane bought him a whistle two years ago. Perry still doesn’t use it.

This off-season, back in Vancouver, Perry will run Kane through drills and on-ice workouts—though Kane says those practices are “a lot more give-and-take” today—as he rehabs from surgery and prepares for his debut in a Sabres sweater. After that, there is much to be seen: Whether Kane will be the centrepiece of an exciting rebuild in Buffalo; whether he’ll stay healthy; whether he’ll achieve that 50-goal season he says is in his future; whether his track suits will stay out of the shower. A lot of eyes will be on this new-look Sabres team, and on Kane, though No. 9 has never been one to avoid the spotlight. “That’s what sports is,” he says. “It’s an entertainment business.”

Photography: Getty; iStock; Jared Wickerham/Getty

Almost Done!

Please confirm the information below before signing up.

{* #socialRegistrationForm_radio_2 *} {* socialRegistration_firstName *} {* socialRegistration_lastName *} {* socialRegistration_emailAddress *} {* socialRegistration_displayName *} By checking this box, I agree to the terms of service and privacy policy of Rogers Media.