The NHL’s power brokers and their power experts have descended on Buffalo this week for the 24th instalment of NHL Central Scouting Service’s draft combine, what has become a fixture on the hockey calendar despite the fact that there are no pucks, no sticks and no ice.

It might be an overstatement to say that it’s unrecognizable from the very first combine. After all there are still 100-plus 18-year-old kids from all over the hockey world who are invited in for physical testing. Then, as now, they all look like they have no idea what they are getting into at the beginning. And then, as now, they all look like they have no idea what hit them by the end.

[snippet id=2850061]

Then, as now, you’ll see a few teenagers who look like grown men. (See Aaron Ekblad three years ago.) And then, as now, you’ll see a few others who could pass for the prospects’ little brothers, plucked out of middle school. (See Mitch Marner two years ago.)

Players, though, are the only constant.

“That first year, it was a mom-and-pop shoestring operation that we put on,” said Chris Edwards, who worked with NHL CSS before moving over to the league’s development program for on-ice officials. “None of us really knew what we were doing. We wanted to get them measured, get an idea of who was in condition, who might have problems, but it was a learning experience for us. We had the bench, the jumps, the stationary bikes, a fair number of the stations that you see now. But from the ‘90s to now, it’s so much more sophisticated. Central has so much more technology available. Teams can know so much more about the players.”

Of course, the site of the combine moved. It had to, really.

In those early days, Central Scouting staged the combine in an airless and dark basement ballroom of the hotel out by the Toronto airport. Execs crowded in a viewing area with seats in the front row reserved for the teams’ strength coaches.

[relatedlinks]

“It wasn’t ideal,” said Barry Brennan, the former strength coach of the Columbus Blue Jackets. “You couldn’t really get a good view of all the stations from any one spot. You’d get screened off. Or there’d be two players who you’d want to look at and they’d be at different stations at the same time. You had to scramble and do the best you could under the circumstances.”

Over time with the addition of new tests and measures, the combine outgrew its confining confines. It didn’t help that the media started flocking to the combine, as it presented an opportunity to get up close to the best young players turning pro. First the combine moved to a conference centre the size of an average-sized hangar out by the Toronto airports. Then in 2016 it moved to the Buffalo Sabres’ practice rink, one with arena seating and bright lighting for better viewing for league officials, not to mention a better setup for media coverage.

This year, the Sabres are again playing host. Said one veteran scout: “It is about seeing the players, but the league is making it sort of a car show … rolling out next year’s models. And that’s changed. Now it’s show biz.”

Said Edwards: “Really, back in the early ‘90s, those first few years, we never thought anyone outside the league would be that interested.”

CROSBY AND OVECHKIN: WHEN THE COMBINE WENT BIG

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when public interest achieved critical mass.

It might have been back in 2004, the year when fans wanted to get an up-close look at Alex Ovechkin, the projected first-overall pick who had been the talk of scouting circles for more than two years. There was a palpable buzz in the room when Ovechkin stepped out on the floor. Thick chested with tree-trunk legs he didn’t just look like he was 30 but also a two-time Olympic gold-medalist in wrestling.

When he was on the stationary bike he generated so much power, you actually had a suspicion that he could set it in motion. Ovechkin’s Wingate numbers, his anaerobic power measurements, were in the top three among forwards and his work output in aerobic testing showed the way but, where others worked desperately, Ovechkin was such a physical freak that he made it look like play. He did the entire process—no one came to a combine with less to physically prove than Ovechkin, but he crushed the tests nonetheless.

And while there’s no measurement for star quality, on an empirical basis, you could tell at a glance that Ovechkin dripped it. After his workout he mingled and joked with reporters. After showering and changing into a muscle-shirt and jeans, Ovechkin returned to the basement to watch the other Russians in their tests. He bench-jockeyed and laughed the whole time. Yeah, he wasn’t just physically fully formed at 18.

The next year it was Sidney Crosby’s turn.

The combine that year fell in the summer after the cancelled NHL season. With no Stanley Cup, and the World Championships and junior hockey season wrapped, attention focused on the combine and the event drew its biggest crowd of media ever. Crosby was at the end of a long arduous season, including a run to the Memorial Cup final that played out less than a week before. He could have taken a pass on all testing—he might have had even less to prove than Ovechkin. Crosby didn’t do the bike, but still did most of the tests and even then put on a display of competitiveness.

Sidney Crosby, centre, looks on as Jack Johnson, right, rides the stationary bike during the 2005 NHL Combine Entry Draft Testing in Toronto Saturday June 4, 2005. (CP PHOTO/Aaron Harris)

Sidney Crosby, centre, looks on as Jack Johnson, right, rides the stationary bike during the 2005 NHL Combine Entry Draft Testing in Toronto Saturday June 4, 2005. (CP PHOTO/Aaron Harris)

Teams came away even more impressed by his interview. Crosby made the rounds, meeting with every team, though the interview process was probably different for him than any other to that point.

Said one director of scouting:

“What exactly was there to interview him about? He’s everything you’d want in a player and, no disrespect to others in his year, but he was so clearly above them, there was nothing at stake. He could have begged off all the interviews but didn’t. When he came in, everyone on our staff just looked around until someone said, ‘Sidney, is there anything that you’d like to ask us?’ We talked—he knew every player on our roster, a complete hockey-obsessed kid. He knew the league like a GM. We had a great talk. He ended up staying for the full 20 minutes on his schedule and more—he only left when he had to make it to another interview.

“I consider the interview the most important thing that we get at the draft combine—I leave the science to the strength and conditioning guys to assess. As a scout, it’s what’s on the ice first, what the kid’s psychological make-up is like and then the physical science. And the thing was, that year, when Crosby didn’t need to talk to anybody, he was the best interview of the week.”

THE INFLUENCE OF E.J. MCGUIRE

Under the current director of NHL Central Scouting Danny Marr, there’s an element of show biz, but still, at its root, the combine is mostly the business of prospects showing what they have to prospective employers. On the floor of the combine, whether on the bench or stationary bikes, whether holding on to the chin-up bar or the unit that measures grip strength, whether jumping high or long, no matter what their exertions and best efforts, the draft-eligible kids coming in are effectively like horses on parade at a yearling sale, not just for the walk-by in front of the buyers’ knowing eyes but taken through their paces.

One man deserves the lion’s share of credit for taking the draft from its humble beginnings to a state-of-the-art fitness testing and physical assessment. “They really should call it the E.J. McGuire Draft Combine,” Edwards said.

McGuire had been a career coach, putting in almost 20 years behind the bench, dividing time between jobs as an assistant coach in the NHL and head man in major junior and the AHL. When McGuire joined NHL Central Scouting in 2002 it seemed a perfect fit.

“E.J. had the hockey background but he also had a degree in kinesiology,” Edwards said. “He understood better than any GM or scout or anybody on Central’s scouting staff what the tests were and what the results meant. He could talk to the technicians doing the tests and the strength and conditioning coaches around the league.”

McGuire became the director of Central Scouting in 2005 and tweaked the combine seemingly every year.

“E.J. and I actually went down to the NFL combine to go to school on what they were doing and we were just blown away by the resources and science they had,” Edwards said. “Our doctors will flag issues if they think there might be something but down at the NFL combine, there were three trucks outside the stadium with MRIs to do evaluations right then and there.”

McGuire focused on developing a dialogue between CSS and the strength coaches.

“E.J. would ask us what we wanted to know, what tests we’d like to see, any changes in the testing, changes in compiling data for interpretation,” Brennan said. “There were tests that individual teams did—what we did in Columbus, for instance—that weren’t done at the combine until E.J. came in and added them. E.J. died a few years back [2011] but a lot of what’s done today was started by E.J., certainly the collaboration with strength coaches.”

That collaboration is more key now than in McGuire’s time. A few years ago, the NHL prohibited teams conducting their own fitness or conditioning tests—presumably, the league’s elite franchises would have greater financial resources and an advantage over others in the second tier. And likewise it prevents prospects and their agents from cherry-picking the teams that they would do private tests for.

“If everyone is working with the same data it’s a fairer system,” Brennan said.

COMBINE ABOUT COMPETE LEVEL AS MUCH AS THE DATA

The public perception is that the combine is a purely scientific process and that the cold hard data tells all. Brennan said this isn’t quite the case.

“If it were really that, then we wouldn’t have to see the testing at all,” he said. “We could just look at the Excel sheets and analyze the numbers. Fact is, though, there’s variation that you wouldn’t know if you weren’t there.”

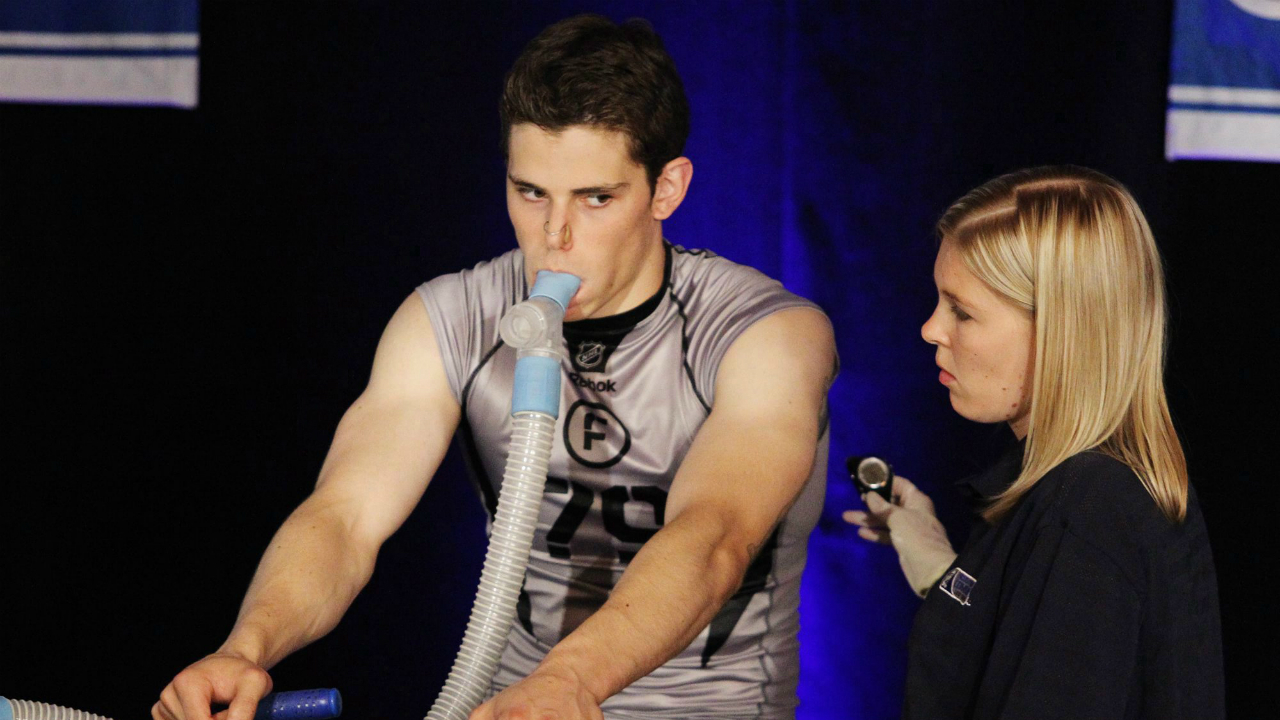

Brennan pointed to one instructive example: “You try to get identical conditions for all the prospects testing but that was never quite the case. You would have Wingate and VO2 numbers but unless you’re there, you don’t know for sure if the kids stayed in a sitting position [as is required in the testing protocol] or stood up to try and get some advantage. You would see some of the players, especially the European kids, who just had no idea of the tests they were doing—maybe they’d struggle with the mouthpiece in the VO2 test. And you’d see some kids who are moved through the tests really quickly, with less rest than others. Some kids would have only 15 minutes between the VO2 and Wingate testing and some would have an hour—that rest would be a huge advantage.”

Tyler Seguin, left, goes through testing during the 2010 NHL Scouting Combine in Toronto Friday, May 28, 2010. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darren Calabrese

Tyler Seguin, left, goes through testing during the 2010 NHL Scouting Combine in Toronto Friday, May 28, 2010. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darren Calabrese

In fact, the latter scenario became enough of an issue that the Central Scouting had to deal with it—VO2 and Wingate tests have now been given their own separate days with the aim to put no players at a disadvantage.

“Really, whether you’re a strength and fitness coach or a GM, at least as much as the numbers, you want to see if a kid is competing hard,” Edwards said. “They haven’t really come up with a measurement for that yet.”