In honour of the 2017 NHL Centennial Classic, we’re looking back at stories we’ve done over the years on key figures in the histories of the Toronto Maple Leafs and Detroit Red Wings. This piece was originally published in June 2016.

I pitied Auston Matthews.

OK, I envied his youth, his talent and his immediate and long-term financial prospects. And yes, I would have at least settled for his lot: being the first prize in Canadian Powerball, more commonly known as the NHL Draft Lottery. Still, at 18, so much of his future was down to the luck of the draw, and he was expected to provide immediate comment on the hand dealt to him. Who among us could have done that? Never mind the fact that Matthews watched the lottery play out in the wee hours of the morning several time zones away. There was probably a script, but he strayed from it when he admitted having “mixed feelings” about Toronto’s lottery win. The whole exercise seemed like soliciting quotes from a pinned-down fly as it first stared up at the noonday sun through the magnifying glass. “I smell something burning,” Matthews could have said. “I think it’s me.”

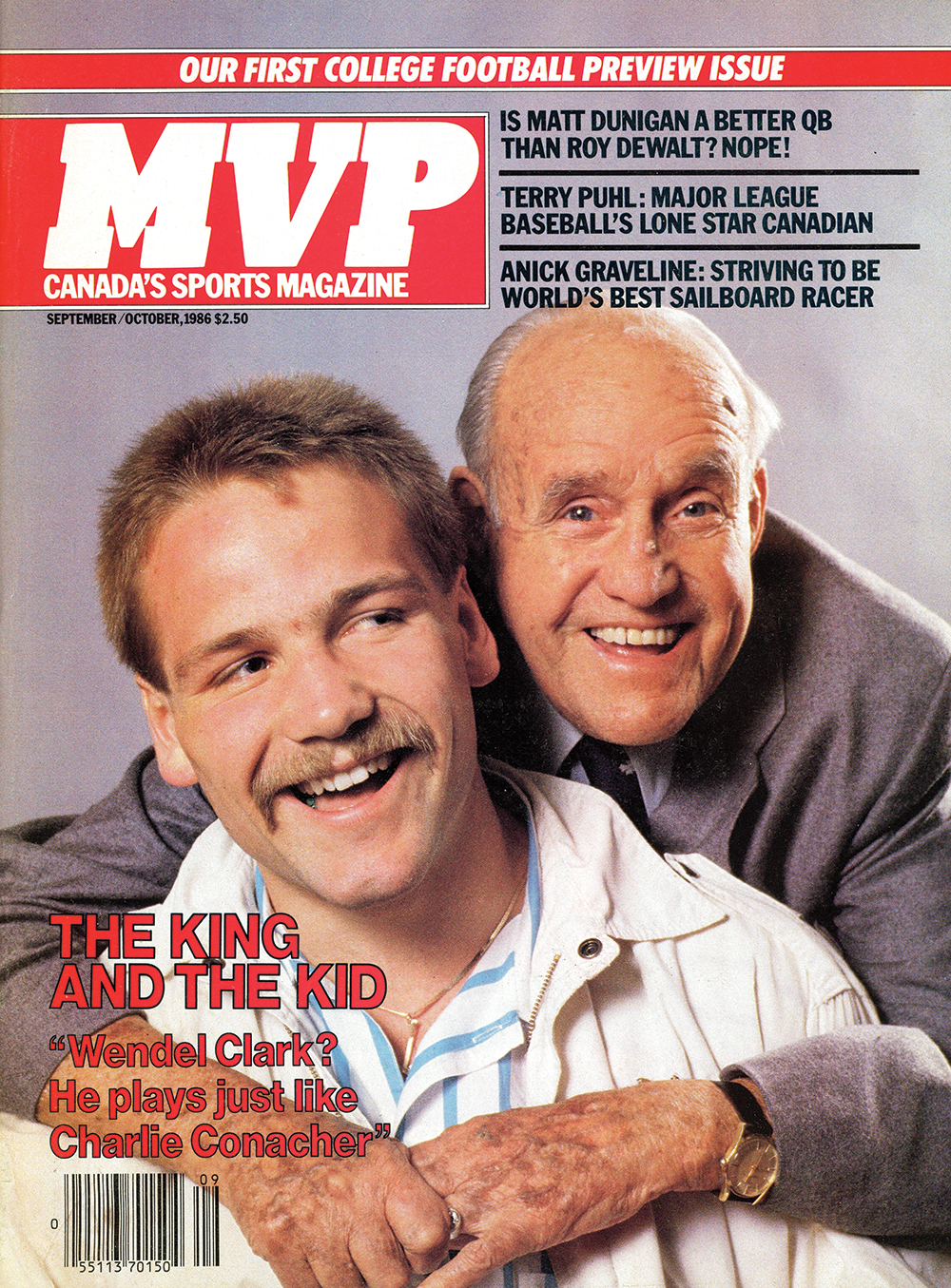

That Saturday night, while Toronto fans were looking ahead to what Matthews might do for a team that had just finished 30th in the NHL, I travelled back 30 years almost to the day, to May 1986, when the NHL was but 21 teams with John Ziegler presiding. I travelled back to a lunch at a members-only bistro long gone in a building that still stands but is utterly transformed. My lunchmates were a man who knew what it was like to be a star in Toronto and a teenager who had just started to find out. That building was Maple Leaf Gardens, the bistro was the Hot Stove Lounge, and lunch was served to King Clancy and Wendel Clark.

Clancy was a fixture at Maple Leaf Gardens going back to its construction in 1931. Even when the Leafs were at various nadirs, Clancy was utterly beloved, a wingman and handy antidote to the franchise’s irascible, irrational owner, Harold Ballard, who lived in an apartment attached to the closet space that served as the Leafs offices. My bright idea was to build a magazine story that was simply a Clancy monologue over lunch, sort of a spin on My Dinner with Andre. My editor gave me the green light conditionally: It had to be Clancy in conversation with Clark.

It only sounds easy. There wasn’t yet a media-relations department per se. I just had to somehow wrangle the pair of them.

At that point, Clancy had slowed down. Bad days outnumbered the good, and both were dwindling down to a precious few. He didn’t waste the good ones, though, popping in to the Gardens in the morning then heading to Woodbine Racetrack. So I staked out Clancy’s parking spot on Wood Street. For a week.

I was on the clock. The Leafs’ season, Clark’s first with the team, had just wrapped up with a heartbreaking loss to St. Louis in the seventh game of the conference semifinals. Still, in Clark, fans, management and even waiters at the Hot Stove Lounge found hope. At 18, he might have had the best wrist shot in the league, and no one played or fought with less fear. But with the season over, I knew he was driving back to the family farm in Kelvington, Sask. At that point, I hadn’t even spoken to Clark. I had to introduce myself then convince him to let me buy him a sandwich. Yes, those were more innocent times.

In retrospect, it would have been a great day to have a lottery ticket. The stars aligned. Clancy hadn’t been around for days but he came in to pick up his mail at the exact point when Clark’s cousin Kelly Chase was idling on Church Street, waiting to pick up Clark and load his equipment and suitcases. I corralled both targets. Clancy’s tomato soup went cold as he told stories of Hall of Famers from the NHL’s gothic early days, with Eddie Shore felling Ace Bailey being just another day at the office. Clancy talked about living at the Royal York for $33 a month, running as sober sidekick to the hell-raising Charlie Conacher and generally having the time of his life. I asked him about his first NHL game, and he painted a vivid picture. “My first pro game was Frank Boucher’s first as well. Ottawa vs. Hamilton, in Hamilton,” he said. “Frank and I didn’t play until the game went into overtime. Mr. Green, the coach, put Frank and I on in overtime, and I scored a goal. To this day, it didn’t go in. It went through the side of the net, but the referee didn’t catch it—and we won.”

Clark tore into a steak sandwich. He was still a farm kid, all about action, not words. I nudged him to talk about the life of a teenage star in Toronto, and it seemed like it hadn’t gone to his head. In fact, it seemed like he hadn’t noticed, more or less going to the Gardens for games and practices and then retreating to the home of Peter Zezel’s parents. I asked him about his first NHL game, just seven months before. “I didn’t think about the first game much when I stepped on the ice,” he said. “I’m not sure who we played. In the warm-up, I thought about how I used to watch the NHL and now I was in it. But as soon as the puck was dropped, I just stopped thinking about it. Some guys try to adjust to the NHL and they get away from the things they’ve done all their lives. I went out and played the game just like I did in junior or midget. When my career’s over, I’ll think about it more.”

So many things have come and gone since then. Clancy died that fall at age 84. After a memorial dinner in his honour, a photo of Clancy and Clark was hung in the lobby of the Gardens, and there it stayed until the team moved out and the fixtures were sold off. By then, Ballard had shuffled off this mortal coil. Clark’s career ended 16 years ago, just about the time when Auston Matthews laced up his first pair of skates in Scottsdale, Ariz. These days, corporate interests control the team and concoct media strategies and all the rest.

It’s a very different hockey world that Matthews will skate into. A different city will want to adopt him, and he’ll feel different pressures. You just have to hope he can find as much fun in it as Clancy and Clark did in their times.

Even as we sat in the Hot Stove Lounge, I knew that this was more than a magazine assignment. This was a chance to play a small role in history. I’m glad it happened, but wish I could do it all over again, to pose questions I left unasked, to get in a photo with them. Which is to say, I have mixed feelings.