While goals are fun to watch, high-scoring shootouts aren’t necessarily essential to have an exciting, viewer-friendly product. When the NHL is at its absolute best, it’s a free-flowing, back-and-forth track meet where outcome of the game is at the whim of a bouncing puck.

As the NHL continues to emphasize and prioritize young, dynamic talent that keeps entering the league and thriving right away, it feels like those type of high-event contests are becoming a more regular occurrence.

Unfortunately, not every team is so lucky to be blessed with an abundance of talent, nor are they willing to embrace that style of open-ended play. [snippet]

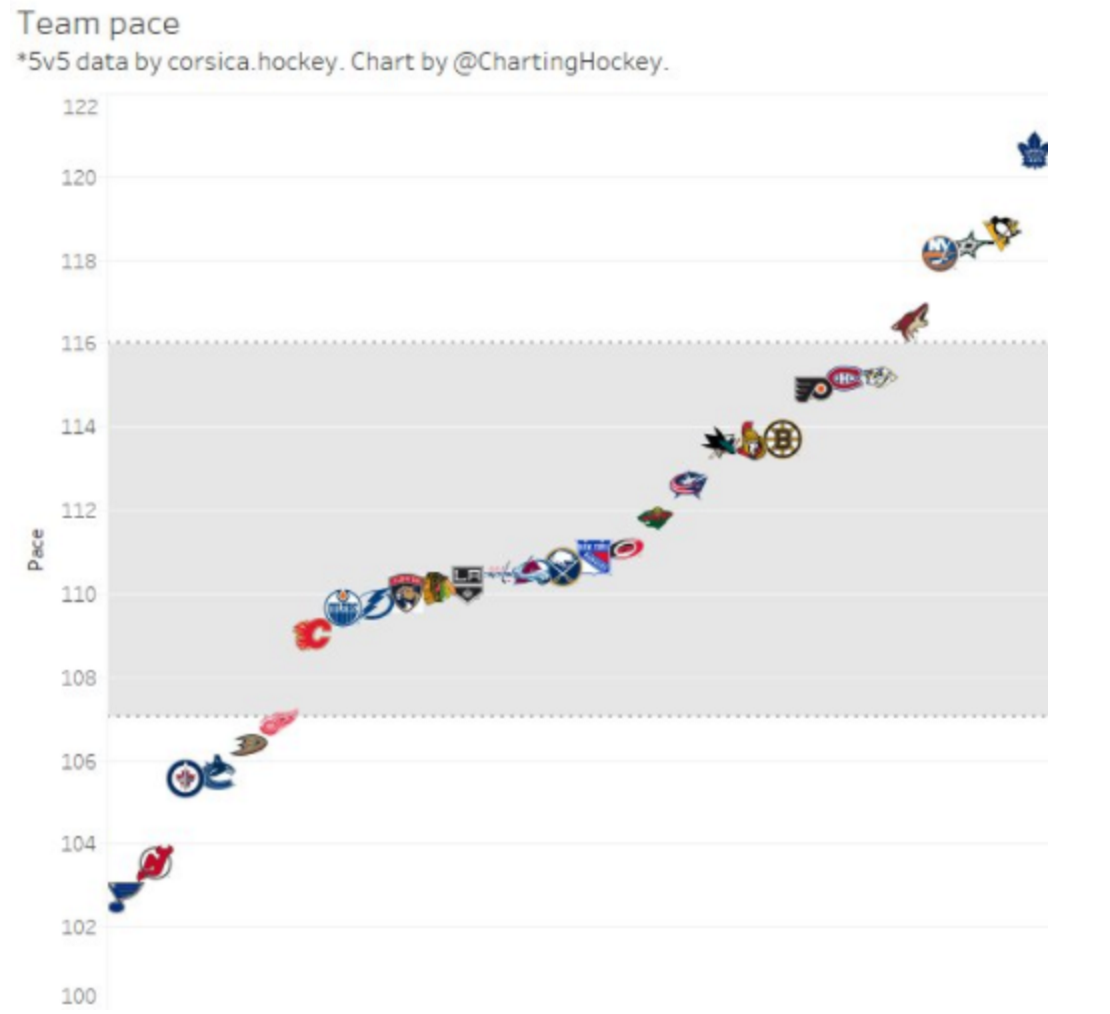

Let’s take a look at how fast or slow each team is playing this season, using the combined rate at which they’re taking and giving up shots during five-on-five play. Using this metric as a proxy for pace is probably the cleanest option we’ve got at the ready, but there’s one glaring caveat that needs to be accounted for first.

One of the byproducts of accounting for what’s happening at both ends of the ice equally, is that it becomes possible to distort the picture for certain teams. The Arizona Coyotes show up as one of the most fast-paced teams, but that may not necessarily be the case.

If you take a closer look at their underlying distribution of shots, they’re being dragged up the rankings by how porous they are in their own zone. No one bleeds attempts against more frequently than the Coyotes, which inadvertently provides the illusion they’re playing fast when they’re more likely just playing poor hockey.

The million dollar follow-up question is: for a team like the Vancouver Canucks, is this really the most optimal brand of hockey for them to be playing? That likely depends on whose perspective you’re looking at it from.

If you’re head coach Willie Desjardins, the answer seems like a resounding ‘yes.’ Whether it’s actually the result of a concerted effort on his part or just simply an unintended function of the way the roster has been constructed is a completely different discussion. But his job is to find a way to win as many games as possible, and theoretically by slowing the game to a screeching halt it increases their chances of doing so.

If you look up and down their lineup objectively, there’s no escaping the unfortunate reality that Vancouver goes into most nights with a skill disadvantage relative to their opposition. One way to strategically combat that is to slow the game down and limit the number of events that occur.

At least in the short-term, a smaller sample size of shots theoretically increases the likelihood of running hot on the positive end of shooting and shot percentage variance, with a couple of random puck bounces here or there (and not true talent) disproportionately determining who wins on any given night. For an inferior team, it seems like a reasonably sneaky way to pull out more victories than you may otherwise deserve.

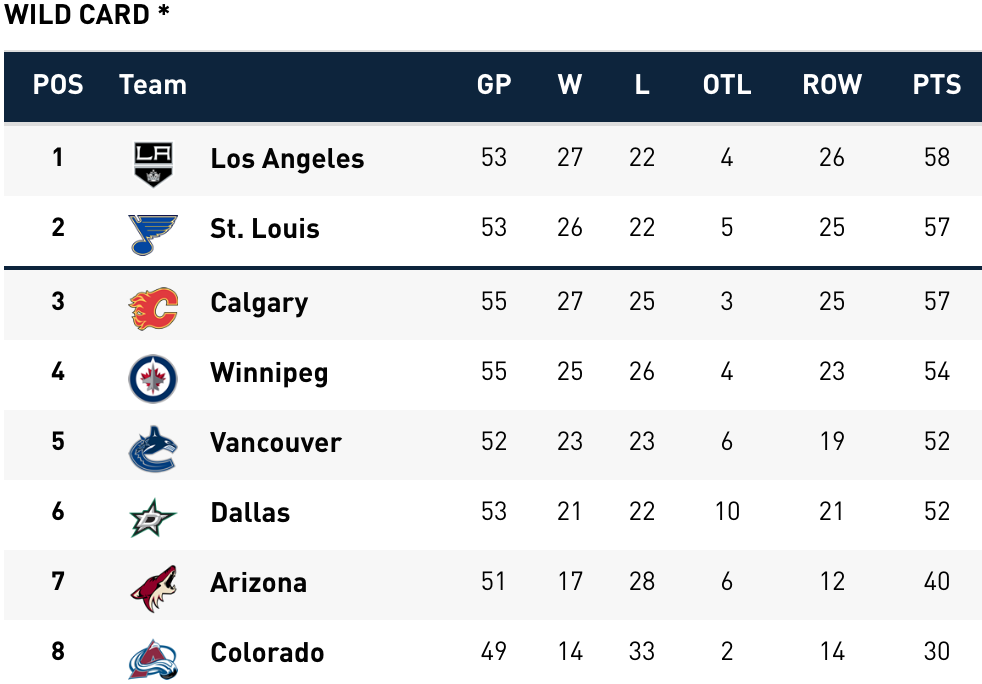

While that style of play is technically keeping the Canucks hanging on in the Western Conference playoff race by the skin of their teeth (they’re only five points out of a wild card spot with one game in hand), if you peel back a layer you realize how paper thin their playoff resume is.

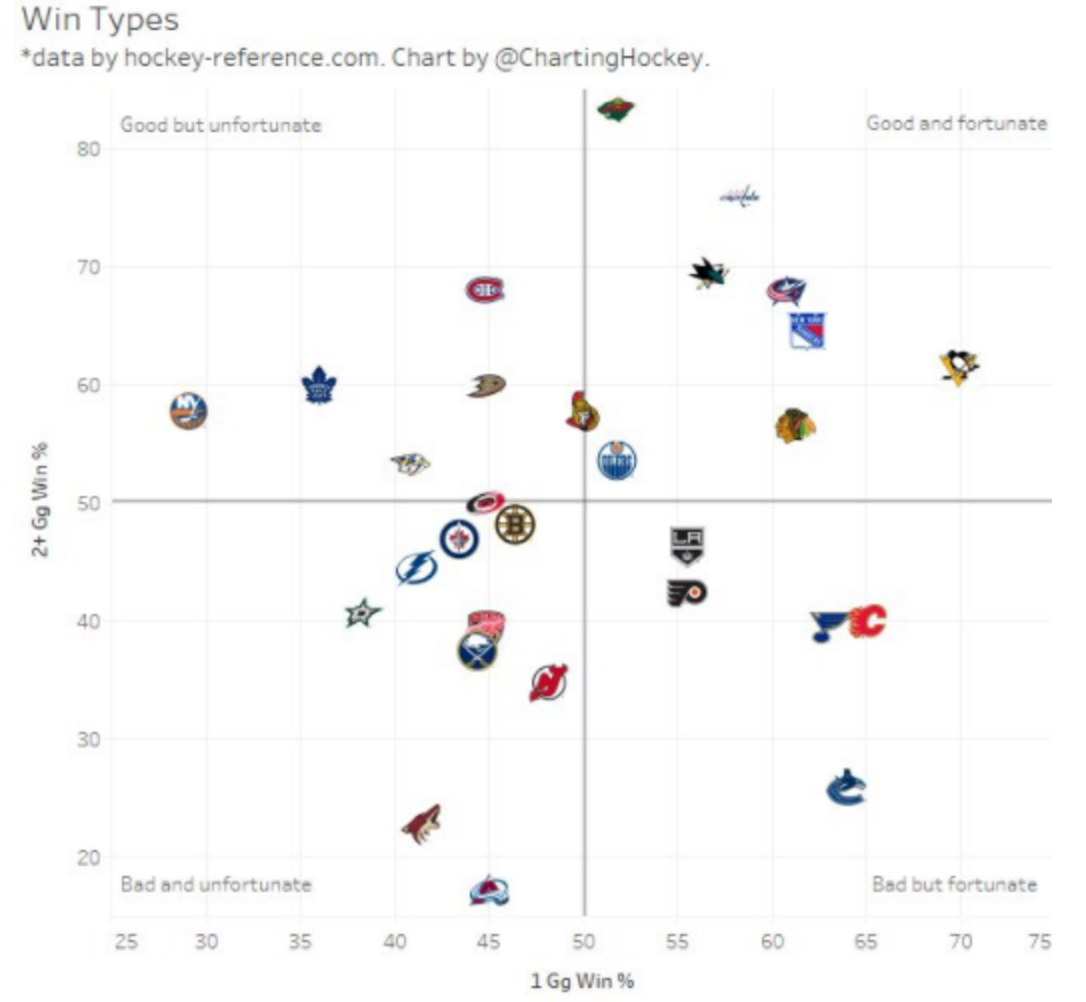

(Chart shows winning percentages in one-goal games and two-plus goal games)

The Canucks have been winning, but they’ve been doing so in an ugly fashion. One of the primary reasons why they’ve been able to stay within striking distance of a playoff spot is because of how fortunate they’ve been in close games.

While they’re third in the league in one-goal game winning percentage, they drop all the way down to 28th in games decided by two or more goals. That puts them in the neighbourhood of teams such as the Avalanche, Coyotes, and Devils, which is probably far more reflective of where they’re at as a team than are the actual standings. As a frame of reference, the top two Western Conference teams in two-plus goal game winning percentage are the Sharks and the Wild, who both showed this past week just how sizeable the gap between themselves and the Canucks really is.

As Vancouver scratches and claws its way through games on a nightly basis, they’re incentivized to muck it up and play slow, boring hockey because it’s the only way they can really mask their flaws and win games.

But at what cost?

Should this mirage endure for a while longer, there are potentially harmful big picture ramifications.

The Canucks’ braintrust has said time and time again they have no interest in a full-scale teardown and rebuild.

Instead, they seem to fancy themselves as a competitive team right now. Their big off-season moves reeked of a win-now mentality – trading three cheap, young assets for Erik Gudbranson and throwing big money at 31-year old Loui Eriksson.

How they handle the next couple of weeks leading up to the March 1 trade deadline will be awfully illuminating. While they’re hardly flush with tradeable pieces, you’d figure players like Jannik Hansen, Gudbranson, Ryan Miller, and even Alex Burrows would potentially be enticing to teams that are loading up for the playoffs.

They’d do well to recoup any prospects or draft picks they can, but based on this management group’s recent track record that course seems unlikely. Last year at this time they stood pat, letting Radim Vrbata and Dan Hamhuis walk for nothing. With each day they hang around the playoff race, it becomes easy to see them taking the same approach this season.

If they do, it would be a gross miscalculation. The more quickly they come to the realization that any success they’ve enjoyed this season is fool’s gold the better off they’ll be for it moving forward.

It’s been tough to watch the Canucks play this season, but it’ll be even tougher to watch them delude themselves into thinking they’re better than they really are just because they’ve happened to be on the fortunate end of a few close wins.

After all, that same unwillingness to assess what’s systemically wrong and makes changes accordingly is what’s led them to this undesirable middle ground spot in the first place – one where they’re not good enough to compete for the Stanley Cup, but not bad enough to fully bottom out.

That’s the worst spot you can be as an organization in today’s NHL and that’s where the Vancouver Canucks find themselves right now.