Complex deals are sometimes made at the NHL trade deadline, but they are the exception rather than the rule. Instead, the most common trades made are simple ones: a pending free agent for some combination of draft picks and/or prospects.

It’s easy to see why these kinds of trades are popular. Bad teams with no chance at the playoffs can convert their departing players into something valuable. Middling teams can improve their chances of clinching a playoff spot at a modest cost. Contenders can borrow against the future to improve their chances of winning in the present.

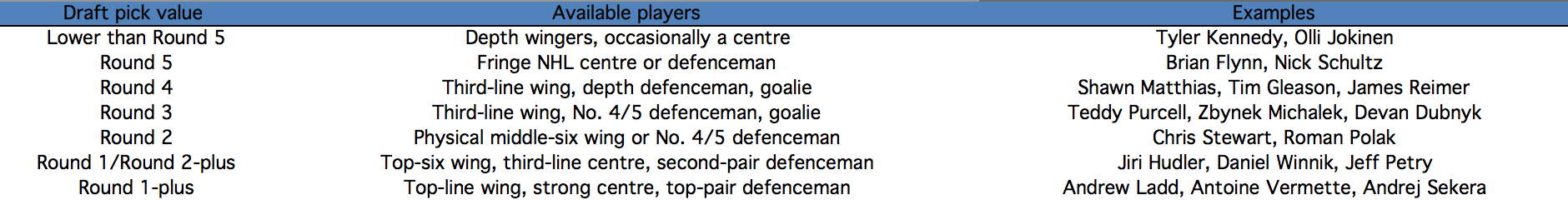

Because these deals are so common, the prices on rentals vary only a little from year-to-year. A seller knows roughly what it should get for its pending free agents. A buyer has an approximate idea of how many futures it’s going to have to cough up to upgrade its roster. But what do those rough estimates look like? [snippet]

At the very bottom of the scale are depth wingers, who are basically worthless because every team has players who can fill those slots. When the New York Islanders needed to add some insurance in the event of injuries in 2015, they were able to acquire Tyler Kennedy for a seventh-round draft pick.

Costs climb quickly for other players, though.

The price of even a bad defenceman generally starts with a fifth-round pick. Nick Schultz, scoring at a five-point pace and getting caved-in by the shot metrics, landed that for the Oilers in 2014. Tim Gleason, averaging just 17 minutes per game for a bad Carolina team the next year, brought back a fourth-rounder and a warm body.

Depth centres routinely come in at around the same price. Brian Flynn cost the Canadiens a fifth-rounder in 2015. Even Olli Jokinen, ineffective and at the end of his career in that same year, commanded a sixth-round pick and a warm body in a deadline trade.

You might assume goalies would fall into the same class, but in fact they tend to be inexpensive — most assess in the range of a third- or fourth-round pick. The principal return on James Reimer was a fourth-round pick, while current Vezina candidate Devan Dubnyk originally landed in Minnesota as a rental in exchange for a third-round selection.

For the same price, a contender could help its roster elsewhere. Third-line wingers and No. 4/5 defencemen start to become available once the draft pick being offered climbs to the third round. Examples from last season include wingers Teddy Purcell and Jamie McGinn as well as defenceman Justin Schultz. A season earlier, Zbynek Michalek landed in St. Louis for a prospect (Maxim Letunov) of about the same value.

There’s always a premium on physical players in the post-season, which seems to be why players who might otherwise fall lower on this scale can fetch a full second-round pick in trade. Toronto got a pair of second-round picks last year for Roman Polak and Nick Spaling, capitalizing on the first’s physicality and the second’s ability to play centre.

[relatedlinks]

Chris Stewart as well cost a second-rounder in 2015. A year earlier, the superior Ales Hemsky commanded a return of third- and fifth-round picks. But Stewart crashes and bangs, while Hemsky plays a finesse game.

For the most part, NHL teams have been reluctant to part with their first-round picks except in package deals. However, many trades in recent years feature a second-round pick plus another selection, the value of which is comparable. Naturally, most of these deals are made by teams that see themselves as legitimate contenders.

Those deals involve players perceived to be top-four defencemen or top-six wingers. In just the past three years, a second plus another significant pick has served as payment for rentals of Marian Gaborik, Jiri Hudler, Jaromir Jagr, Jeff Petry and Daniel Winnik. If Winnik seems out of place, it’s because of the premium put on centres.

That premium also helps to explain the Antoine Vermette trade in 2015. Chicago, loading up for a Stanley Cup run, shipped a first-rounder and fringe NHL defenceman Klas Dahlbeck to Arizona in exchange for the veteran pivot. It was a lot to pay, but centres are hard to find and the Blackhawks did win the Cup.

The Rangers didn’t give up a first-rounder last year when they brought in a slumping Eric Staal, but with two second-round selections and prospect Aleksi Saarela going the other way they certainly surrendered at least that much value. Recent years have also seen a top-line winger (Andrew Ladd) and top-pairing defenceman (Andrej Sekera) bring back a package centered on a first-round pick.

There’s little question as to what the oddest deadline rental was of the past three years: the St. Louis Blues’ addition of starting goalie Ryan Miller and fringe NHLer Steve Ott in 2014. If we include Buffalo’s subsequent trade of Jaroslav Halak (who was part of the return), the Sabres landed a massive package from a position that usually doesn’t yield much:

• A first-round draft pick

• A third-rounder and a conditional third-round draft pick

• Winger Chris Stewart, dealt the next year for a second-round pick

• Goalie Michal Neuvirth, dealt the next year for a third-round pick

• Prospect William Carrier

• Defenceman Rostislav Klesla

That deal is a reminder that a player’s value comes down to what a trading partner will pay. If that team has a burning need, or there’s a marquee player coming back, the trade return can be exorbitant.

On the whole, though, rental trades fall into the framework established by previous deals. Depth guys and goalies are cheap, centres and defencemen always have value, and first-round picks move less often than packages that are built around second-rounders.