It looks less like a hockey stick than a big wooden comma, or a prop from the Harry Potter broom closet. It lives for now in a climate-controlled vault, swaddled in bubble wrap and touched only by hands encased in protective gloves. But it’s a miracle this thing that’s now handled with such care survived at all. It started out in the hands of a boy scrambling across a frozen Cape Breton lake. A couple of generations later, it kept popping up on a woodpile as a tantalizing kindling option, before it was moved to the wall of a barbershop and basically ignored while three decades of local gossip unfurled below. But this strange little piece of wood—the oldest known hockey stick in the world, with a genealogical and scientific trail that leaves virtually no doubt about exactly what it is—is the hockey equivalent of a perfectly preserved dinosaur fossil.

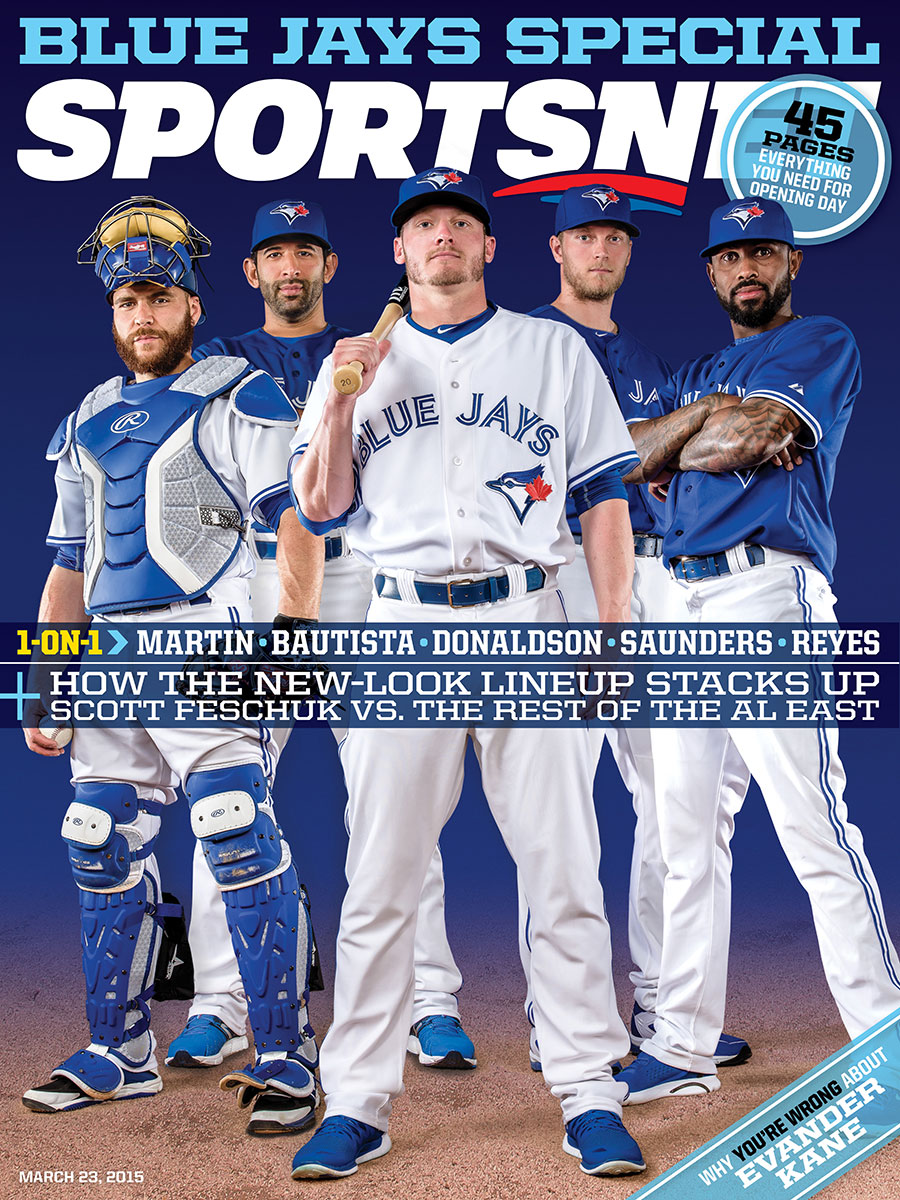

Sportsnet Magazine’s Toronto

Sportsnet Magazine’s Toronto

Blue Jays Special: From the heart of the order to the bottom of the bullpen, we’ve got this team covered in our preview issue. Download it right now on your iOS or Android device, free to Sportsnet ONE subscribers.

As a kid, Mark Presley never rolled his eyes when his uncles or grandfather got going on tales of what the world was like when they were growing up—he begged for more. The past has always shimmered a bit for him. So when a grown-up Presley and his wife, Linda MacNamara, moved back to her native Cape Breton and his father-in-law mentioned that a barbershop in North Sydney, N.S., had a very old hockey stick on display, Presley paid a visit. Just over a metre long and a hefty 1.75 lb., the stick was slung over an old wooden sled mounted on the wall; you’d miss it if you didn’t know to look. “I had no place else to put it,” says barber George Ferneyhough. “I never thought more of it. It was just a piece of wood to me.” A few years later, in 2008, Presley happened to grab lunch next door, and he ducked in to see if the stick was still there. It was, but the shop had been stripped down because Ferneyhough was preparing to retire. The barber told Presley a little about the Moffatt family that had owned the stick, which he guessed was 100 years old. A hockey fan and memorabilia collector from childhood, Presley was intrigued and asked if Ferneyhough would consider selling it, floating an offer of $1,000. The barber readily agreed—he would have just given the thing to his grandchildren—and then Presley paused. “I thought, ‘How am I going to tell my wife I spent $1,000?’”

Hungry to learn more, Presley arranged a visit with Charlie Moffatt, who’d given it to the barber 30 years before. Moffatt was in his 90s by this point, so Presley expected to hear how he’d played with the stick as a boy. But Moffatt said his sticks came from Canadian Tire, and it was his father and grandfather who had used this one—the first indication of just how old it was.

It had hardly been treated as a treasured heirloom. John Hannem, Charlie’s stepson (Charlie died in 2011 at age 94), remembers how the stick would show up on the wood pile next to the white enamel stove in the kitchen on the Moffatt farm. Charlie would stride into the room, scoop it up and jokingly bark, “Don’t burn my hockey stick!” His wife, Joyce, gave it some serious thought, because that crooked old piece of lumber looked more like kindling to her. “I’d think to myself, ‘Oh my gosh, would I love to burn you!’” she chuckles. Maybe the only reason the stick survived is because Charlie was an incurable collector of everything, from cinema flyers to pins from the bombs he dropped in the Second World War. “I think he put it down at the barbershop just so Mom wouldn’t burn it,” says Hannem.

The biggest mystery about the stick was also a major clue—the initials “WM” carved into the blade. Charlie’s father was Warren, but the stick couldn’t have been his originally if Charlie’s grandfather, Thomas, had also used it. Then Presley discovered that Thomas had a brother, William—nicknamed “Dilly”—eight years older and born in 1829. If the stick was Dilly’s, it provided an earlier glimpse of hockey than anything else out there. The International Hockey Hall of Fame in Kingston has a stick from 1888, and Montreal’s McCord Museum has another from 1881. What was thought to be the oldest stick in existence is at the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto, dated to the 1850s.

Presley became consumed with a desire to learn more about the stick. In early 2009, he got in touch with Colin Laroque, director of the Mount Allison Dendrochronology Lab in Sackville, N.B. (dendrochronology is the science of dating based on tree rings). Laroque agreed to take a look, but didn’t expect much. “We get a lot of these calls—‘Can you date this?’” Laroque says. “The answer, 90 percent of the time, is no.”

But when Presley arrived carrying the stick in a foam-filled metal rifle case, Laroque was amazed to find enough visible tree rings to work with on the butt end. He agreed to take it on as a learning project for his students; he wouldn’t charge Presley, but they’d take as much time as they needed. “It’s either a chunk of wood and you go burn it because it’s worthless, or it’s worth hundreds of thousands of dollars,” Laroque says.

Finally, after almost two years of work, the lab came up with what they felt was a solid birthdate for the stick. They determined it was carved from a sugar maple—almost obnoxiously Canadian, really—cut down between 1835 and 1838. The timeline fit perfectly with the Moffatt family tree, suggesting the stick had been made for Dilly when he was between six and nine years old. And that made it the oldest known hockey stick in the world.

Presley built a website chronicling the stick’s provenance and listed it on eBay with a reserve price of just under $200,000. The Canadian Museum of History was watching. Last March, with 24 hours left in the auction and bids reaching $100,000, the museum asked Presley to put things on hold so they could negotiate. After giving the stick a thorough physical and consulting professional appraisers, the museum settled with Presley on a purchase price of $300,000. And though the barber has grumbled that it would be nice if he got a cut, the Moffatt family is thrilled with how things turned out.

Dilly Moffatt’s stick will soon be a key exhibit in the new Canadian History Hall opening on Canada Day in 2017, 180 years after the little boy would have grabbed it and run down to Pottle Lake, on the edge of the family farm. Back then, there were no pads or proper gloves; the nets were likely strategically placed rocks; and with the puck not yet invented, Dilly would have chased a tin can or a frozen cow pie. Everything that now defines the game—Lord Stanley’s cup, gap-toothed heroes, blurring speed—was far off in the future. But still, it would have looked like hockey.

This story originally appeared in Sportsnet magazine. Subscribe here.