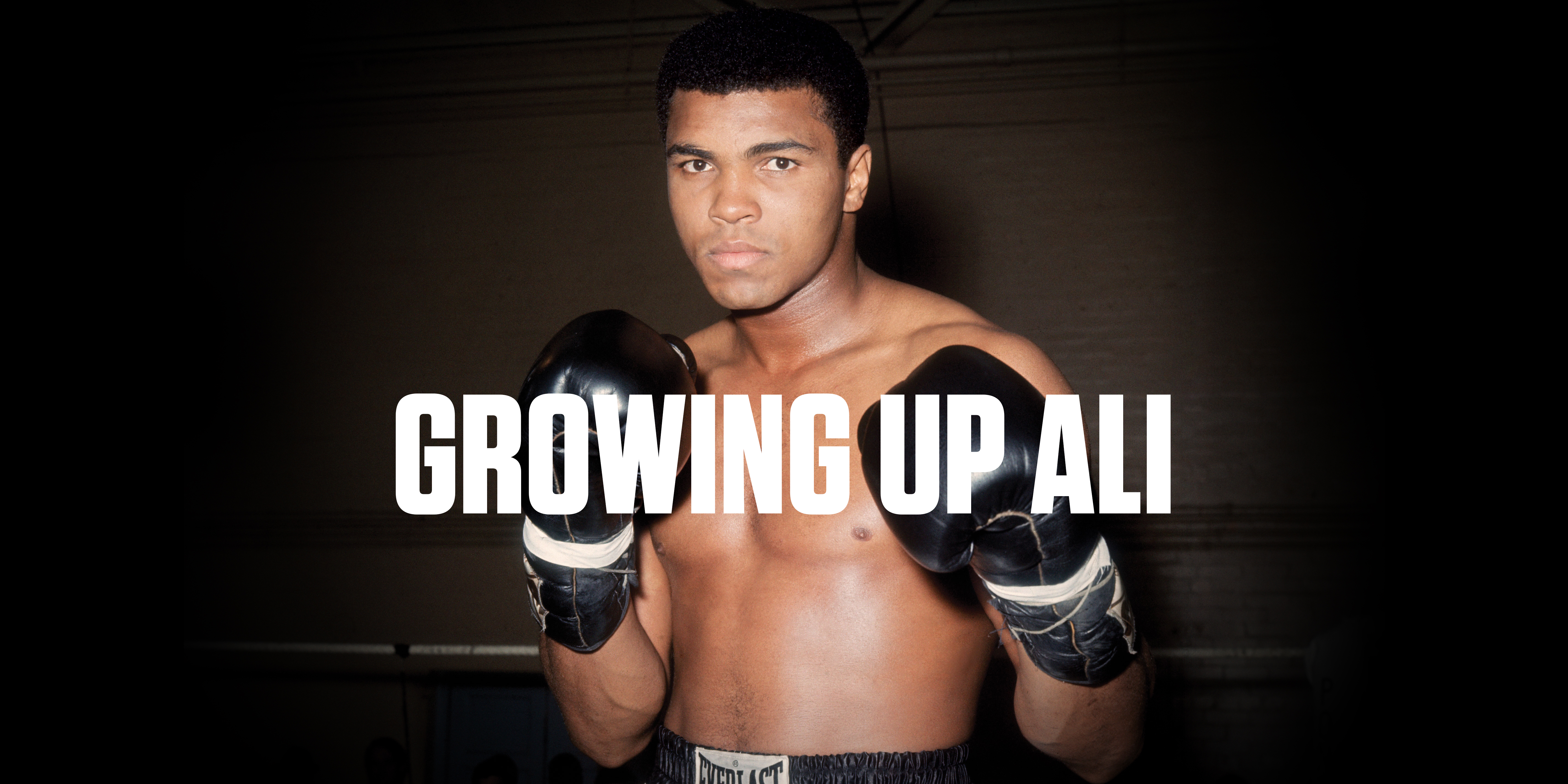

When I was seven, I discovered the champ. Twenty-five years later, I knocked on his door.

By Stephen Brunt

He looked up from the table where he had been carefully, precisely signing a stack of religious tracts, fighting hard to still his trembling hand, his voice not much above a whisper. “How old were you when you first heard about me?”

That morning in 1991, at his country home near Berrien Springs, Mich., Muhammad Ali was trying to get a fix on the latest stranger who had come to his door unbidden. “M. Ali,” the sign at the gate said. There was an intercom but- ton beneath it. A friend of mine who had briefly been in the Ali orbit told me how it worked. People from all over the world arrived all the time. Ali loved the company, loved the attention. After a life lived in the global spotlight, he preferred to be in a crowd, even after his brain and body had begun to break down. Visitors were nearly always welcome.

So we drove there, my wife and me and our two sons, then age three-and-a-half and one, taking the detour on a lark on our way home from a wedding in Chicago. “We’re from Canada,” I said through the intercom.

The gate swung open and we drove down the long driveway, passing a carload of Germans on their way out. Lonnie Ali, Muhammad’s wife, welcomed us at the back door, led us through the kitchen where she was preparing lunch with her mother, and took us into the living room where Ali sat and where he asked the question.

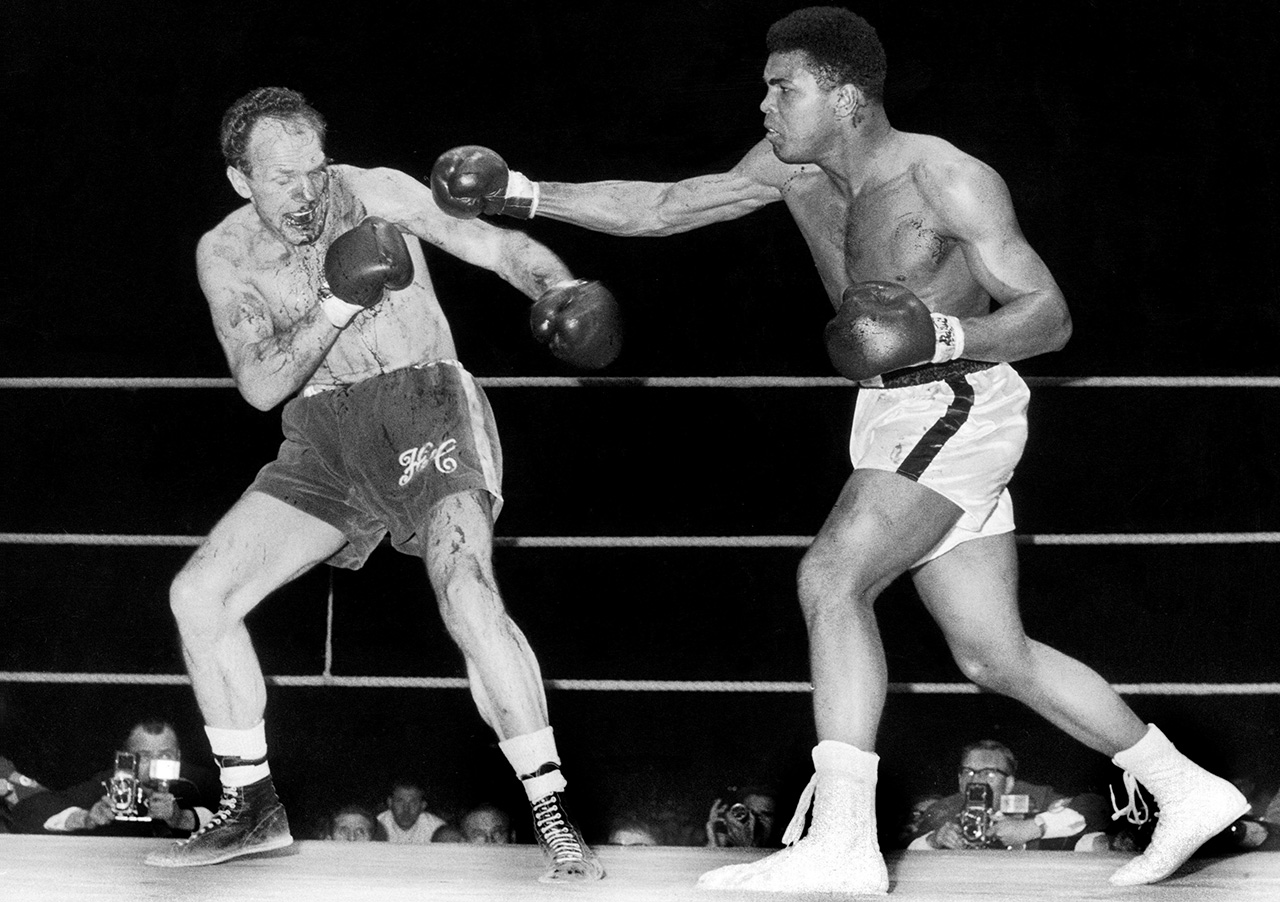

It was 1966. I was seven. The second fight with Henry Cooper. Black and white television. ABC’s Wide World of Sports. With my father, who loved boxing but didn’t much like Ali, which was the majority opinion among those of his generation. Nearly everyone still called him Cassius Clay.

Cooper, a charming cockney with a great left hook and parchment-thin skin who had nearly beaten Ali the first time they fought three years earlier, had him down and almost out before the bell sounded to conclude the fourth round. Then Ali’s trainer Angelo Dundee complained of a torn glove and for a moment confusion reigned. During those seconds Ali regained his senses. He then came out and proceeded to cut Cooper to ribbons, ending the fight in the fifth.

The rematch was for the heavyweight championship of the world, the most glorious title in all of sport, a crown Ali had captured with his “shock the world” upset of Sonny Liston, followed by the phantom-punch knockout in the rematch in Lewiston, Maine, 15 months later.

Because Cooper had come closer than anyone to knocking Ali out, he was regarded as a very live underdog when they met for the second time with the title on the line.

The English fans appreciated Ali’s act. When he arrived in London for the first Cooper fight in a crown and a cape emblazoned with the words “Cassius the Great,” they ate it up. But there were no doubts as to their true rooting interests. They stood foursquare behind Our ’Enry, hoping that he might become the first British heavyweight champion since Ruby Bob Fitzsimmons stunned Gentleman Jim Corbett with his solar plexus punch in 1897.

Instead, Ali toyed with Cooper. He was getting better. He was impossibly fast of foot and hand. Again cuts proved decisive.

“I was seven,” I said.

That’s the point, isn’t it? We have all had that moment, nearly every one of us on this planet Earth, when we became conscious of Muhammad Ali. It could have come earlier, during the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, when he won the gold medal that he later claimed to have chucked into the Ohio River in an act of political protest (wasn’t true, it turned out—he just lost it). It could have been during those early years as a pro, when he seemed more like comic relief than a future great, his act borrowed in large part from the wrestler Gorgeous George.

It may have been later, when it became clear that the victories over Liston, however odd, were no fluke, when he was beating all comers and cleaning out the division. Or when he announced that he had a new name, that he was now a member of the Nation of Islam, and suddenly for many the act didn’t seem quite so funny. The courtroom drama, the exile, the triumphant return, the Fight of the Century in 1971—all moments when Muhammad Ali was at the centre of a global conversation, both as an athlete and as a symbol of political and social change, of the split between generations, of the chasm between black and white.

Then came his remarkable third act—Zaire and Manila—when, though robbed of much of the speed and reflex that had made him different from any heavyweight before or since, Ali won two prize fights that read like novels, defeating the apparently unbeatable George Foreman with guile and subterfuge, then outlasting his great rival Joe Frazier, the yin that completed his yang, through sheer force of will, leaving some of his essence behind in that ring.

People a little too young to remember those remarkable nights might have tuned in for the late fights, Ali desperately holding on, running on empty, unwilling or unable to walk away, each one turning into a struggle for survival: Ron Lyle; Earnie Shavers; the two with Leon Spinks, including that final triumph in New Orleans; the horrific spectacle as Larry Holmes did what he was paid to do, beating down his mentor; the last sad go-round with Trevor Berbick, when the toll taken on Ali’s body and brain was already evident.

Things went quiet until 1996, the climax of the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games in Atlanta, when Ali’s surprise appearance, vulnerable and frail as he held the torch and lit the cauldron, finally, fully reconciled him with mainstream America in part because the man who had once seemed like a revolutionary, whose views and values had once seemed so threatening, had become a kind of silent, suffering martyr whose maladies were a direct result of the sport that made him (and that he remade in his own image), meaning that all of us who had watched were at least a little bit culpable in his demise.

There are many ways of looking at Muhammad Ali beyond the shrunken Buddha of his latter years.

As a fighter he was a one-off, an original. There may have been others before him with a more complete skill set, like his idol, Sugar Ray Robinson, and in discussing the heavyweight pantheon, there are historians who would suggest that he lacked the technical precision of Joe Louis, or that Jack Dempsey (though he would have looked tiny standing next to Ali) would have imposed his savage will, or that Jack Johnson (Ali’s only true pre- cursor, able to do things his contemporaries couldn’t in the ring, while rebelling against the social and racial mores of the time outside of it) could have beaten him on his best night. Ken Norton, on no one’s best-ever list, bedevilled Ali all three times they fought, though that may simply be proof of the old axiom “styles make fights.”

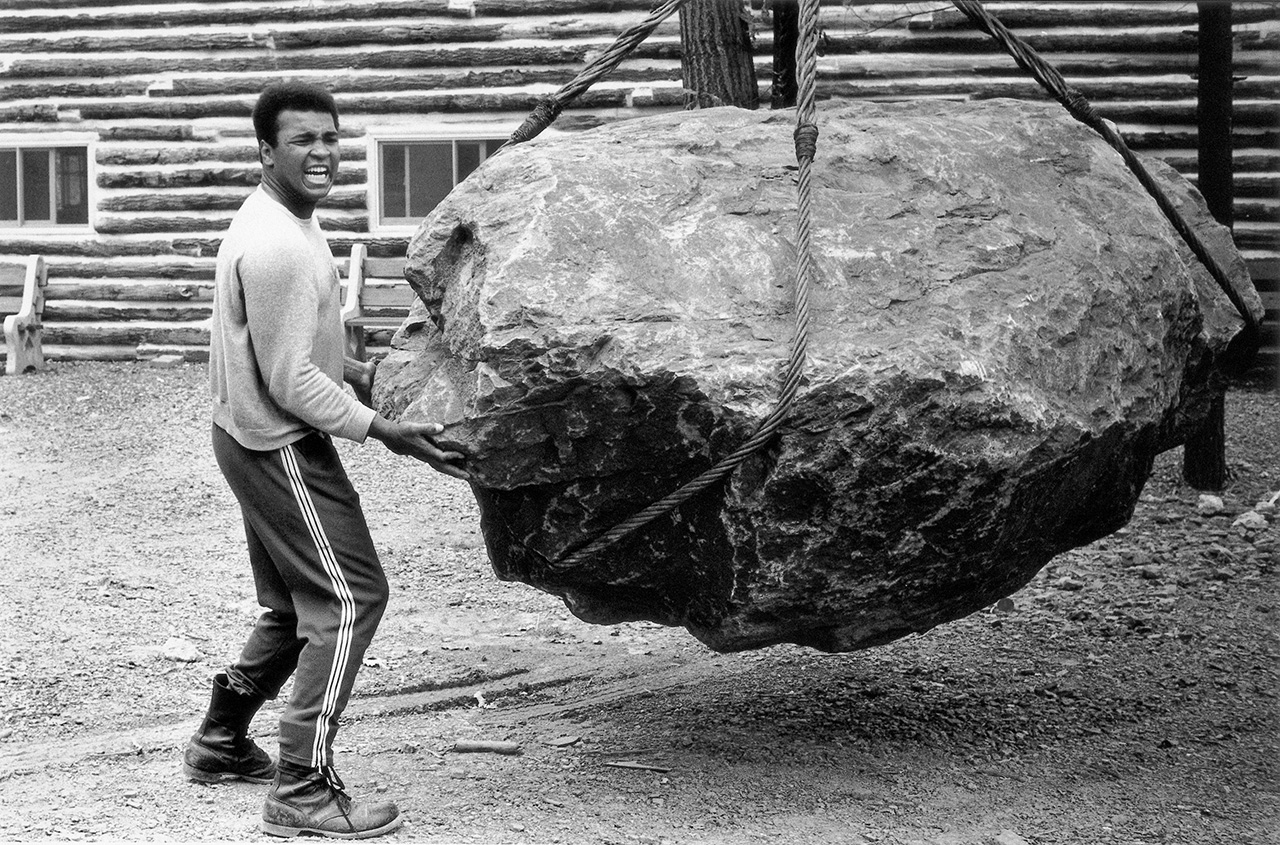

Here’s the bottom line, though: Never before and not since has there been a boxer like Ali, someone that big, someone who could throw punches that quickly in combination, who could move around the ring on his toes like a dancer and still remain on the attack. What he did “wrong”—leaving his guard low, leaning back and away from punches rather than blocking them—would have been fatal flaws in other, less gifted fighters. With Ali, his unique style, his unparalleled skill set, allowed him to box exactly the way he chose. In 1966 and 1967, just before he was forced into exile, you could make the case that no one in the sport’s long history could have beaten him, and who knows what he might have looked like during those lost three-and-a-half years.

The Ali who returned from exile was different, and in many ways diminished. He could no longer dance his way through an entire fight. He had to pick his spots. He was much easier to hit. And because of that, he was forced to draw on qualities most never knew he possessed: a brilliant tactical sense, allowing him to outwit opponents even in fights where he was physically overmatched because of advancing age or less-than-peak conditioning; an ability to absorb punishment without wilting, both to the body and to the head—even battling on with a broken jaw against Norton in their first fight—an asset in the ring that almost certainly contributed to his later medical issues; a fierce will to win, which only failed him at the very end, when there was just nothing left.

Ali is also without question a man of conviction. Whether one regards Elijah Muhammad as a spiritual leader or charlatan, Ali’s con- version to the Nation of Islam was a decision that would dictate the course of both his professional and personal life. It flew in the face of convention in the early 1960s—not just convention in the form of the white, Christian establishment, but also of the civil rights movement and its African-American leader- ship. The “Black Muslims” were racial separatists who rejected the idea of integration, and the truth is that when taken seriously, they happily alienated most people, white and black alike.

When the young, charismatic, heavyweight champion joined their ranks, the mass perception of Ali immediately changed. The traditional boxing crowd had been slow to acknowledge his talents, and his act, his poetry, his boasting, had been widely regarded as harmless clowning. Now, there was no denying his mastery in the ring, while outside he delivered Elijah Muhammad’s message without even the hint of a smile. Forced to make a choice between Malcolm X, who had guided his conversion, and the Nation’s hierarchy, which had ordered its members to shun him, Ali chose the Nation, and was unwavering even after Malcolm’s assassination.

The Nation of Islam reshaped Ali’s world view, it caused him to walk away from the white Louisville businessmen who had backed him when he turned professional, and make Elijah’s son Herbert Muhammad his man- ager (Dundee somehow managed to survive that transition). And of course his faith was the reason he defied the draft, an act that would cost him what might well have been his greatest years as an athlete.

As in all things, there was in fact some grey wrapped around that black-and-white decision. Ali had thought he wouldn’t be drafted because of his low score on an IQ test. It was only after the battlefield toll grew rapidly, and the pool of the draft-eligible shrank, that Ali and others were reclassified and moved to the front of the line. He was shocked when that happened. He was scared. When he said, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” it wasn’t so much a coherent religious/political statement as it was the same thing being said by all kinds of young men who didn’t have a rich daddy who could get them a deferment: I don’t want to go over there and get killed for no good reason.

Even after it became clear that no one was going to send the heavyweight champ into actual combat, that at most he would be used as a propaganda and recruiting tool as had Joe Louis during the Second World War, even after his spiritual advisors in the Nation quietly agreed that if they could cut a deal to keep his career going while he was in the Army—and keep the cash flowing—it would be fine by them, Ali stuck to his principles, not knowing if he would ever be allowed to box again, facing the real possibility that he would go to jail.

That act of conscience, of self-sacrifice, would come to define Ali, and transform him from a sports star into some- thing the world had never seen before—and hasn’t really seen since—a worldwide athletic celebrity who chose to stake out a strong and controversial political position, to the detriment of his own career.

At the time when he made his initial declaration, most Americans supported the war. By the time he was allowed to resume his career in 1970 that support had eroded, and Ali had become a beacon—especially for the young, for the dispossessed, for the people of the Third World. Beside him, the only other athlete in history to at least temporarily enjoy a similar global reach, Michael Jordan, looks like an empty commercial shill.

But for all of that iconography, Muhammad Ali is also no saint. Those deeply held religious beliefs didn’t stop him from being a lousy, unfaithful husband—especially to his second wife, Belinda. (I remember interviewing Holmes, his former sparring partner, who expounded at length about his old boss’s voracious sexual appetites. “I know how he lived. I knew what he did. I seen the people come into camp and leaving camp. I knew he walked around with a stiff dick every day… He would f–k a snake if you held its head. You don’t even have to hold the motherf–ker’s head. Just give him the snake.”)

Ali is also possessed of a cruel streak. It was there when he tortured Ernie Terrell, punctuating the punches with shouts of “What’s my name?” after Terrell had had the temerity to call him Cassius Clay. It was there when he kept Floyd Patterson upright in order to inflict the maximum amount of pain, because Patterson had publicly questioned Ali’s Muslim beliefs.

It was especially there in his interaction with Frazier, whom he unfairly cast as an Uncle Tom, whose looks and speech he mocked, whom he referred to as a “gorilla.” Those slights, uttered while beating the promotional drum for their three fights, hurt Frazier deeply, and he lacked the intellectual and verbal dexterity to counter. All he had was his left hook—and then, in later years, after Ali had been rendered nearly mute, Frazier’s own clumsy retorts (he suggested after Atlanta that he wished Ali had fallen into the Olympic cauldron) earned him only disdain.

There is no question Ali softened as he aged. His Muslim beliefs evolved along a more ecumenical path (just as had Malcolm X’s), diverging from the militant posture represented by Louis Farrakhan after Elijah Muhammad’s death. Though simple pathos was also a part of it, with the sport and the divisive war that made him famous little more than a nostalgic memory, Ali became a unifying figure, the danger long gone. Subtly, the official explanation for his infirmities shifted. At the time Tom Hauser wrote his excellent authorized oral history of Ali, the doc- tors who had treated him made it clear that he had suffered brain damage from boxing, that the sport, those who ran it, and those who loved it, were in large part to blame. Those in charge of the Ali business shifted the narrative: it was Parkinson’s disease that Ali had, not boxing-related Parkinson’s syndrome. He was like Michael J. Fox. It had just happened. It was just bad luck. Seeing him like this, one could feel empathy or pity, but one didn’t need to feel responsibility. It wasn’t anyone’s fault.

That was a disservice to the real Ali, as have been some of the painful public appearances in recent years (one at the Rogers Centre in Toronto before an Argos game, and the worst at the opening of the new Marlins ballpark in Miami), done only for the money, when he has seemed barely there.

That said, though the crowds may have been shocked at his appearance, their love and admiration for him seemed undiminished. And who knows what Ali was thinking behind that Parkinsonian mask. For a man who needs to live his life in public, who feels naked minus a crowd, perhaps it wasn’t so bad.

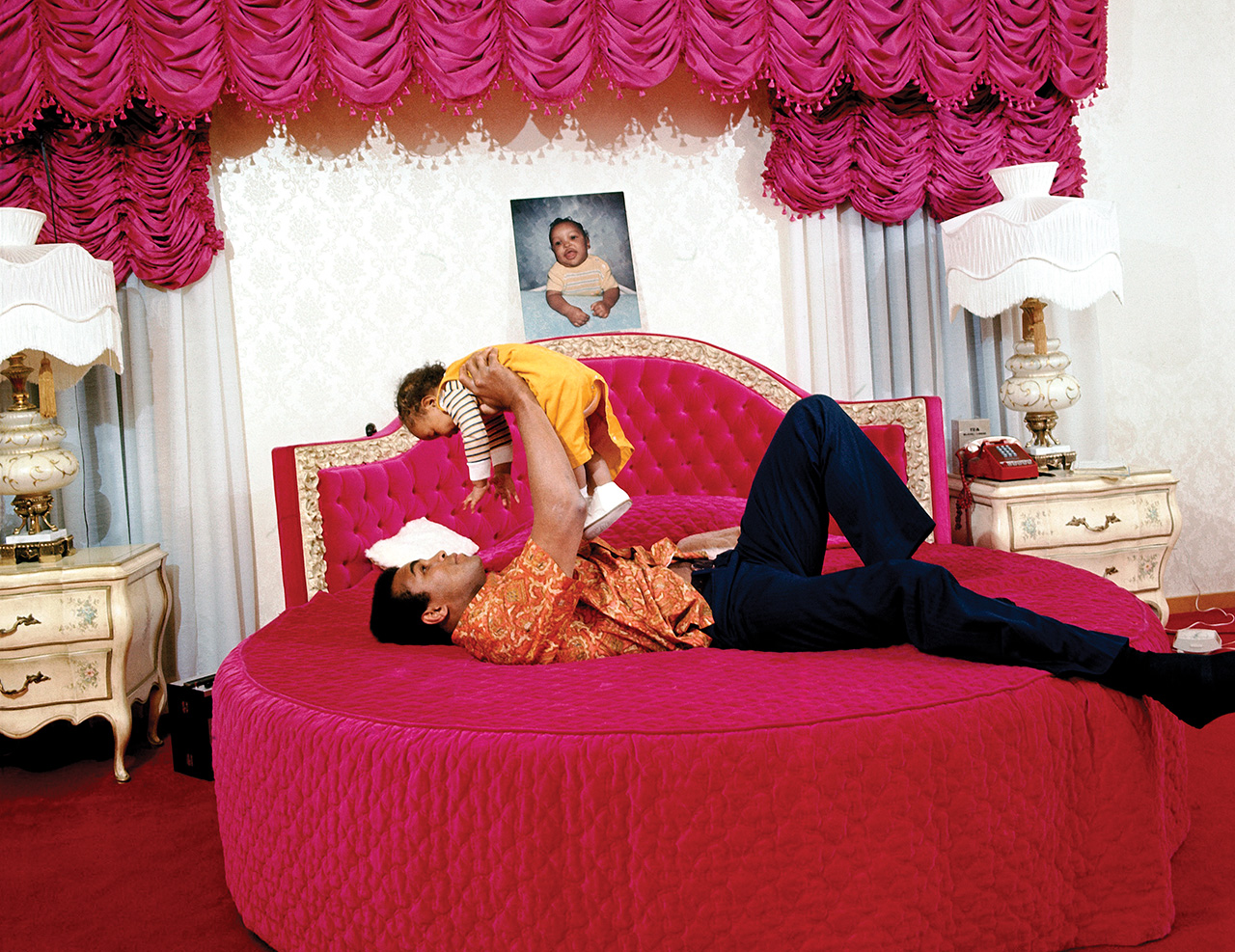

Back to the visit. I have told this story many times. It is written here as I wrote it just after it happened a long time ago. Those little boys are grown men now, as is Ali’s son, Asaad.

There is no pressure to leave Ali’s home. Others who have visited have been fed, have stayed for hours. When we decide to depart, he rises and walks us to our car.

Outside, he takes his boxing stance, flicks a few jabs, and invites me to flick a few in return. Then a woman appears from behind the house, holding Ali’s recently adopted son, Asaad, who is four-and-half-months old and bears a striking resemblance to his new father. It is his eighth child and the only one who lives at home.

He holds the baby, kisses him, then hands him gently, gingerly, to my wife. Stepping back, Ali stumbles over a sleeping dog and nearly falls, as stiff as the tin woodsman after a hard rain. Even as he appears about to crash, only his eyes have expression.

Regaining his balance, Ali walks ahead a few steps and glances back over his shoulder at my elder son and me. “Watch my feet,” he says. Ali turns his back, stands with his feet slightly apart and steadies himself. Then for an instant he seems to rise from the ground, levitating. My son stares in wonder.

I stare, too, and during the moments before reason kicks in, before the rational ties that bind the rest of us to earth expose the fakir’s trick, I believe with all my heart that Muhammad Ali has ascended.

“How did that man fly?” my son asks and asks and asks for days afterwards.

“It was magic,” I tell him. “It must be magic.”

Trevor Humphries/Getty; Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images; Getty Images; Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images; Bettmann/Corbis

Almost Done!

Please confirm the information below before signing up.

{* #socialRegistrationForm_radio_2 *} {* socialRegistration_firstName *} {* socialRegistration_lastName *} {* socialRegistration_emailAddress *} {* socialRegistration_displayName *} By checking this box, I agree to the terms of service and privacy policy of Rogers Media.