Jurgen Klopp coming to Liverpool has been more of an emotional transition and a tactical adjustment than anything else. A manager coming to the Premier League for the first time to fix a struggling club whose expectations unrealistically reflect a dominant past has many obstacles to hurdle.

Since consistently winning the league in 1980s and a sprinkling of success in 2004-05 when they won the UEFA Champions League, Liverpool has been craving similar achievement. But, besides a single season in 2013-14 when Luis Suarez single-handedly slayed the Premier League, they haven’t been close to being good enough.

During Brendan Rodger’s recent tenure at Liverpool, an open, possessive style was given three seasons to marinate. An evolution in firepower from his days at Swansea City, Rodgers had potent weapons at his disposal and attempted to integrate them into his possession-based roots.

It never fluidly mixed as it seemed over-thought and often was represented on the field as a team with two independently moving halves of the same body. Rodgers therefore had to react to losses and some unforeseen outcomes, and happened to find success through the forced hand of his third or fourth formations, and positional options (see the timing of the emergency reflex of three at the back during the 2014-15 Premier League season). It finally caught up to him, and he was ousted.

Enter Klopp, and enter the same questions of every outside, idealistic, European manager coming to the Premier League. Can staunch ideas of tactics, positioning and movement, which were successful in other leagues in Europe, continue to be successful in the Premier League? Can a manager who heavily leverages the direct communication of emotion and passion be as effective while not using his native language?

Well, it’s been about three months and a few points can be made: Klopp has no issue communicating and transferring his emotional message to his players or the fan base. He is also an adept enough of a manager to understand that creating a carbon copy of his Dortmund or Mainz sides with this group of Liverpool players, and maybe even this league, would be a rushed choice.

Shots on Target Ratio (SoTR) and Total Shots Ratio (TSR) for Rodgers (Matchday 1-8 of 2015-16 in Red) and Klopp (Matchday 9-23 in blue)

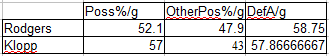

Through his first 15 Premier League matches in charge Klopp’s Liverpool is averaging more possession (57 percent) and less defensive actions (57.9) per game than in Rodgers’ beginning to the season. They want to continue to keep the ball and now suffocate teams in certain areas of the pitch to regain possession and break on the counter attack.

Rodgers through first eight matches & Klopp through next 15 matches of 2015-16 season

This had led to an increasingly better Total Shots Ratio (TSR), which is a proportional comparison of total shots in a single period, but a declining Shots on Target Ration (SoTR), a similar comparison of shots on target. So, although the new system is producing a better total of shots for rather than shots against, Liverpool is struggling to increase its total of quality chances.

Although both Rodgers and Klopp have managed different clubs in the past, the most interesting—albeit the miniscule sample size— comparison is their performances and tendencies with the same players and club. Klopp coming into Liverpool was supposedly bringing a thunderous pressing game with a fast and ruthless counter-attack. Yet, when you take a closer look at his Dortmund sides the pressing was quite managed and punctual, while the counter-attack was absolutely ruthless. This was looked at here by Karl Matchett.

Liverpool with high pressing line to opposing goalkeeper, individuals pressing on their own with support of team shape.

This is indicative of the style of pressing that each deploy. Rodgers was a fan of a high press that extended to the opposing goalkeeper (similar in vertical distance covered to Mauricio Pochettino’s positional press at Tottenham). As the team’s line was high already, this allowed the Liverpool players to press individually with the confidence that their teammates would already be in a position to cover.

This allowed for wide gaps to open, and if the opposition were to break down and figure out Rodgers’ first line of pressing, they would have a good chance of success through the midfield spaces.

Liverpool setting up medium block; as ball gets into midfield, two players hunt as pack and ball is won.

Klopp’s press is deployed in a medium block, wherein the line of confrontation is further regressed towards midfield. The advanced players are not encouraged to press towards the opposing goalkeeper, but rather to force the opposition’s possession to one side of the field, and then press in packs. Much has been made of Klopp’s “gegenpress,” which is a style of counter-press that encourages specific pressing when possession is lost, but this doesn’t completely detail his total defensive structure.

As a system is brought to a club by a manager, rather than having the manager completely adapt or even create a system of playing according to the personnel at their disposal, it will inevitably take longer time for it to settle. Klopp currently has some pieces in place that he has shown a liking for that might fit into his mold of Liverpool for the future (see Can, Firmino, Moreno, Coutinho and Lallana), and there are some pieces that clearly need some fixing or replacing (see Benteke … well, just see Benteke).

No matter the tangible table result, having strong characters with fresh ideas from different parts of the world is good for the Premier League from a tactical and analytical standpoint. Now, let’s see if Klopp can best Rodgers.

Coleman Larned is soccer analytics writer based in Antwerp, Belgium. Follow him on Twitter